Don’t count on Fed rate cuts to save the economy from recession

The US economy may very well avoid a recession in the coming months. But if it does, it probably won’t be because of interest rate cuts from the Federal Reserve.

As the unemployment rate rises and job openings and payroll data continue to soften, the Federal Reserve has decided it’s time to ease policy in the months ahead in hopes it can prevent the US economy from entering a downturn.

But history shows that effort may be futile, and that if a recession is coming, it’s likely already baked in.

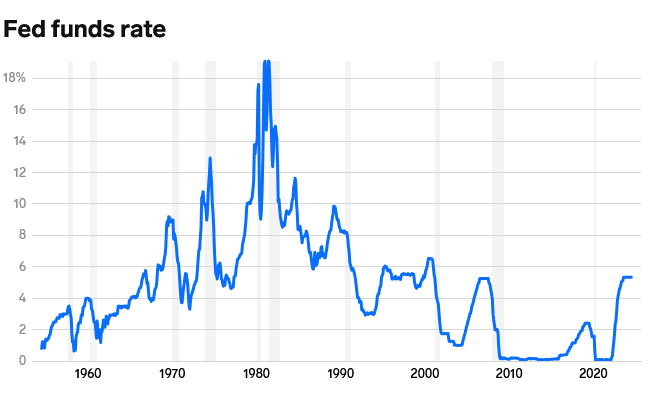

Here’s a chart showing the federal funds rate over the last several decades. Recessionary periods, as identified by the National Bureau of Economic Research, are highlighted in gray. Often when the Fed has cut interest rates while the US economy has not yet entered a recession, a downturn still follows anyway. Other times, the economy was already in recession when the NBER looked back to mark when it began.

Such was the case in 2008, 2001, 1989, 1981, 1980, 1970, 1960, and 1957.

The Fed is credited with delivering soft landings in 1984, 1995, and 2019 — though the economic cycle following the 2019 cuts didn’t get the chance to play out under normal circumstances with COVID-19 throwing the global economy into recession in early 2020.

So while soft landings have happened, the Fed’s track record on delivering them isn’t exactly impressive. Excluding 2019, 80% of cutting cycles since the 1950s have coincided with or were followed shortly after by a recession.

Why? According to Northwestern Mutual’s Chief Investment Strategist Brent Schutte, it’s partly due to the Fed making policy based on stale data.

“Part of the reason initial rate cuts have had a dismal record in preventing a recession is that the Fed typically starts to lower rates only after signs emerge that the labor market is weakening,” Schutte said in an August 26 note. “Given that labor data is a lagging indicator, it raises the question of whether the Fed is already too late in drawing its line in the sand of maintaining the current employment picture.”

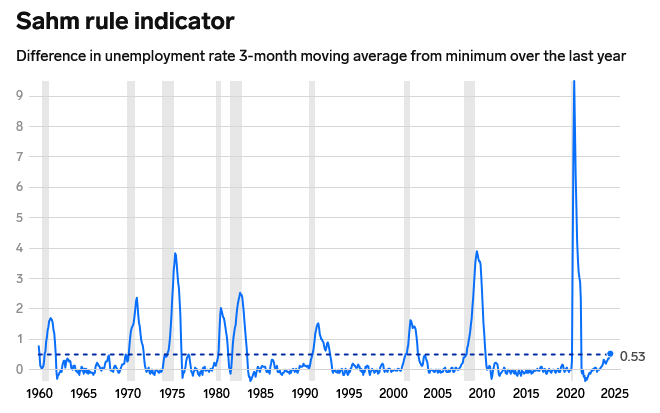

The trouble with the Fed being behind on rate cuts is that a weakening labor market tends to snowball. Look at the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate. Once it rises 0.5% from its 12-month low — which has happened during every recession since at least 1960 — it usually gets much higher in a short period.

This measure is the famous Sahm Rule recession indicator, which was triggered in early August when July’s unemployment rate rose to 4.3%. While Claudia Sahm, the rule’s creator, believes this time is different in that the US economy is not yet in recession, she doesn’t think the labor market is trending in the right direction and has said the Fed should have already cut rates.

Neil Dutta, the chief economist at Renaissance Macro Research, also told B-17 in a recent interview that the Fed is late on cutting rates, and that it’s not easy to turn around a labor market that’s heading in the wrong direction. Points of concern for him include the falling quits rate and falling job openings, which put downward pressure on wage growth, hurting consumer spending.

But the Fed being slow by acting on outdated data is only one side of the equation — there’s also the time that it takes for Fed policy to take effect. Rate hikes and rate cuts usually don’t impact the economy immediately, as the central bank itself repeatedly acknowledges.

While estimates vary from a few months to a couple of years, a commonly accepted range for the full effects of policy changes to take effect is around 12-18 months. That would mean the full impact of the Fed’s rate hikes are just starting to be felt, and a 25-basis-point cut at the FOMC’s September meeting and subsequent reductions would have a while until they fully benefit the economy.

This is one reason Desmond Lachman, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, is worried the US economy is headed for a recession in the next year.

“If you wait till the recession and then you begin cutting, it’s too late,” Lachman told B-17 earlier in August. “The Fed needs to anticipate these things.”

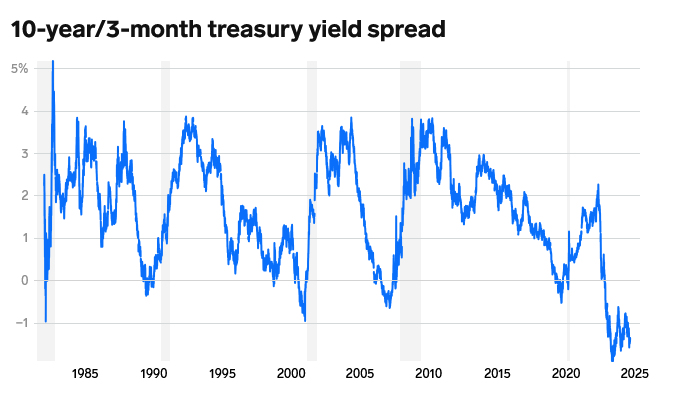

There are plenty of signs that the economy is not yet in a downturn. And if a recession doesn’t come to pass, it’s probably a sign that the Fed did a good job calibrating how high to raise its policy rate. Rob Arnott, the founder of Research Affiliates, once pointed out to me that Australia has avoided recessions since the early 1990s because of what he sees as a “direct consequence” of their central bank not inverting their government bond yield curve. In other words, they didn’t overdo it on the short end with rate hikes.

Interestingly, in the 1984 and 1995 soft landings, the Fed also did not invert the Treasury yield curve when it hiked rates. In this cycle, the yield curve has inverted at its deepest level in four decades. Inversions of the 3-month and 10-year yields (when the line dips below 0 in the chart below) have preceded every recession since the 1960s.

But the downturn is yet to come — maybe the extraordinary amount of pandemic stimulus has strengthened demand enough to withstand aggressive rate hikes this time around. Or maybe not.

Either way, there’s no denying that the data is getting worse. And history shows that rate cuts are unlikely to stop that trend anytime soon.