As Hollywood gets back to work, new rules bring new pain points

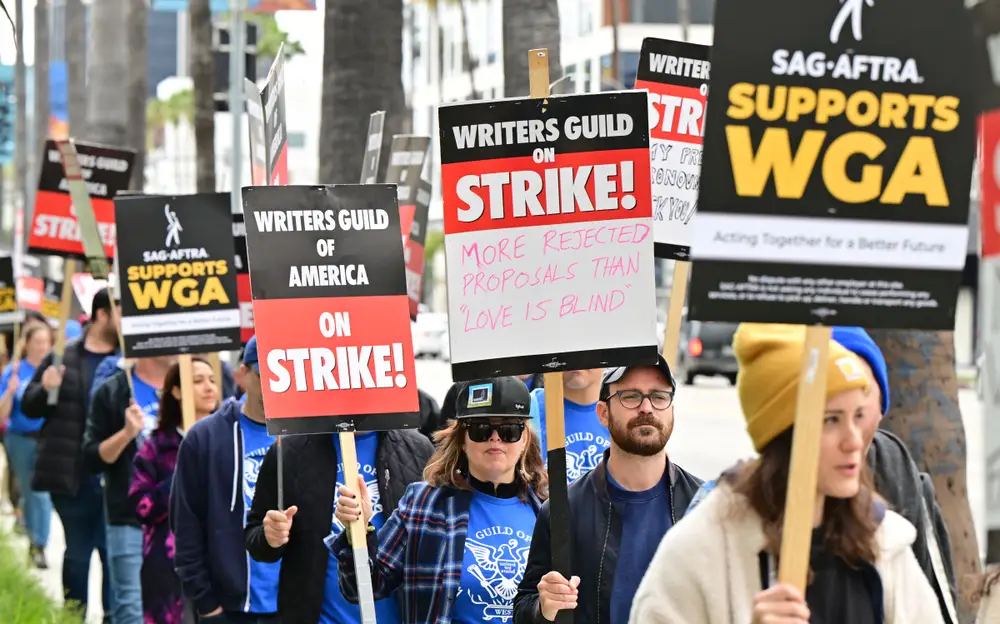

Writers picketed during the Writers Guild of America strike.

Striking Hollywood writers and performers fought hard last year for minimum pay increases and other benefits and protections. It was the first time in more than 60 years that both unions went on strike at the same time.

But as production picks back up, some are asking: Was it all worth it?

After a monthslong strike last year, SAG-AFTRA actors won minimum pay increases and other benefits. The WGA won higher pay and residuals for its writers, provisions for minimum staff in television writers’ rooms, and more, calling the agreement “exceptional.”

But with fewer shows being ordered and with smaller budgets, some are calling into question the actual gains.

Spending on new entertainment content had already slowed down before the strikes when Netflix had a growth hiccup, causing Wall Street to question streaming’s profitability. Moviegoing is still on an ongoing decline. Since the strikes ended, Warners and Paramount have written down $15 billion in the value of their cable networks.

Tracking company ProdPro found the total number of productions filming in the US was down 37% in the first half of 2024 versus the same period in pre-strike 2022.

Along with the fall-off in production, film and TV employment has declined 25% since its 2022 peak, accelerated by the strikes, according to an Otis College of Art and Design study.

Questions about the WGA plank emerged during negotiations. Some showrunners expressed concern that proposed staffing minimums could mean a loss of autonomy over how they hire.

“The conglomerates have the leverage,” one TV agent put it. The agent, like others, spoke on condition of anonymity to protect business relationships. “The majority of writers I work with are all thinking: ‘Why the hell did we strike?'”

With studios shrinking their budgets for shows, showrunners are naturally limited in the number of people they can hire for writers’ rooms, where TV scripts are traditionally produced and honed. Writers’ rooms that might have employed 10 or 12 people in broadcast TV’s heyday are often staffed at half that today, leaving fewer job opportunities in a market that had previously expanded to meet the needs of Peak TV.

“People thought the market would get back to what it has been,” a second agent said. “There’s twice the amount of writers as there was in 2008.”

Beyond the fact that there are fewer dollars to spread around, one concern among writers is that studios are trying to take advantage of the ability — under the WGA contract — to have solo-writer shows like “The White Lotus.”

“Most people feel there are intentions to skirt the contract,” said one TV writer, who requested anonymity to protect job prospects. “People say there are more showrunners being asked to write all episodes so they don’t have to have a room.”

AI’s encroachment continues to worry Hollywood

Also vulnerable, for better or worse, are the controversial writers’ “mini rooms” that emerged in recent years.

Mini rooms rose during the Peak TV era as a way to produce some scripts early on in a show’s development. This model could lead to a show getting picked up, but it tended to use fewer writers than regular writers’ rooms and pay them less. Mini rooms also have been criticized for giving fewer opportunities to newer writers.

A third agent said some showrunners are grumbling that while mini-room writers’ pay increased post-strike, studios kept the showrunners’ pay the same.

“I’ve had a couple showrunners joke, ‘I feel like my number two has a better gig,'” this agent said.

One writer, Zoe Marshall, offered a more positive take. Marshall, an “Elsbeth” writer and WGA West board member, has been in three writers’ rooms since the WGA contract took effect. She said not only did her mini room pay increase 73%, but the problem of late pay had diminished.

“Maybe it’s just a cultural understanding that we are not playing around with our money,” she said. “We’re not only demanding higher compensation, we want to be paid in full and on time, and people seem to finally understand that.”

Another signature gain, the reward for success for streaming titles that are hits, is also an issue. Few titles are expected to qualify for the bonus. And Christian Simonds, an entertainment lawyer with Reed Smith, said SAG actors are strictly enforcing their rights to financial assurance from independent producers, which can put an immediate financial strain on producers’ already tight budgets.

“It’s a pain point,” Simonds said.

Then there’s artificial intelligence, whose encroachment has spooked Hollywood. The writers won a requirement that studios and production companies disclose if any material given to them was generated by AI. Actors also won protections against the use of AI.

But since then, Google parent Alphabet and Meta, along with OpenAI, have sought to get Hollywood studios to provide their entertainment content to let the tech companies train their AI models. OpenAI is encouraging filmmakers to use its text-to-video tool, Sora. AI continues to gain adoption in pre- and post-production. Some have expressed concern that the union contracts’ language is too broad and has multiple loopholes. Rolling Stone reported some SAG members have since said they felt pressured to consent to the creation of digital replicas of themselves.

Entertainment lawyer Jonathan Handel, who reported on the strikes for Puck, called the squeeze on budgets and AI’s continued encroachment the biggest issues facing Hollywood now. Studios remember all too well how they helped Netflix become the streaming behemoth it is today by licensing their content for years. And it’s still an open question how studios should value their content for AI training.

“Everybody’s second-guessing, but what they’re second-guessing are the AI provisions, and now that there’s less work, what did we strike for?” Handel said. “People are shell-shocked that there is so much less work, period. People are increasingly terrified of the effects of AI.”