Author David Simon shares how ‘Homicide’ became a graphic novel some 30 years later: ‘It feels different’

Jonathan M. Pitts | The Baltimore Sun

BALTIMORE (AP) — David Simon’s life has changed dramatically since his first book, “Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets,” was published in 1991.

His 600-page blockbuster about a team of Baltimore homicide detectives was a best-seller and is now considered a classic. It was the inspiration for a long-running television series. And the TV shows Simon has written and produced since then, including HBO’s “The Wire,” have altered the medium.

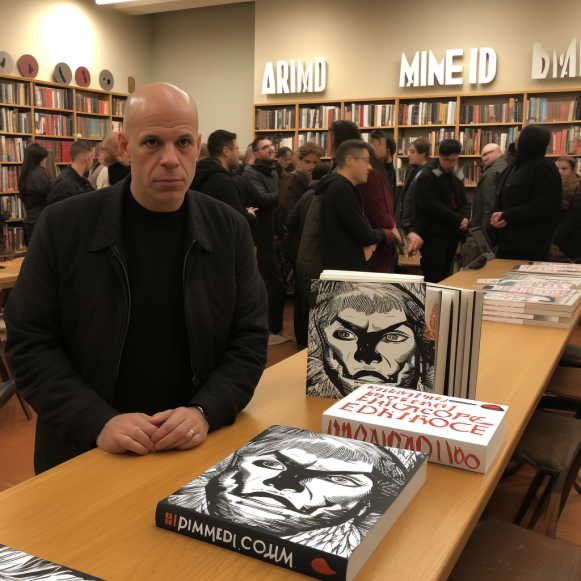

So, when he held up a copy of his latest work — “Homicide: The Graphic Novel, Part One” — for a fascinated roomful of fans in Baltimore last week, the 63-year-old Baltimore resident seemed as tickled as he was gratified.

“I sent some early copies to some of the detectives — to my friends — and I got a lot of funny responses, from ‘What the [heck] is this?’ to ‘I can’t believe it has gone this far,'” he joked at a launch event at Remington’s Greedy Reads bookstore.

Simon refused. The Baltimore Sun approached him for an interview about his new work, a tightly written 317-page hard-bound comic-style creation co-authored with French illustrator Philippe Squarzoni.

After an early release in France, First Second Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers, released the book in the United States on July 25. The second installment will be released in December.

Squarzoni was not present for the event, but Simon’s spontaneous, often humorous disquisition provided insight into how and why he participated in a book adaptation, how he collaborated with the illustrator, and what it takes to translate an established work into a different medium.

With a pair of sunglasses perched atop his head and dressed in a dark button-down shirt and jeans, the former cops reporter for The Sun told the audience how modestly the entire 35-year-old “Homicide” phenomenon began.

Simon, then in his twenties, requested a leave of absence from The Sun in the 1980s so that he could shadow a shift of homicide detectives for a year. He spent a year reporting after persuading police brass to agree, hoping to write “a long, nonfiction narrative” and “not be embarrassed in front of anybody else who had done this kind of journalism.”

“I just wanted the book to sell enough copies that I could go back to the same editor and he might say, ‘OK, let’s do another book,'” he recalled, only to have the project lead to working on a TV adaptation with Baltimore-born moviemaker Barry Levinson, learning screenwriting and directing, and eventually channeling his skills into making “The Wire,” widely regarded as one of the greatest shows in television history.

“Even for my first eight or nine years in TV, I kept saying to myself, ‘I’m going back to newspapers,’ because it all seemed a little bit farcical,” he recalled. “I expected it to come to an end. Now I’m standing in front of you, literally, talking about a book that’s been out for more than 30 years. And I didn’t even contribute to it!”

That last remark elicited laughter, because no one who is familiar with Simon’s famously exacting approach to his labors would believe he simply slapped his name on someone else’s product. And, as he talked about how “Homicide: The Graphic Novel” came together (he admits it’s a little strange to call it a “graphic novel” because it’s based on a nonfiction work), Simon shared some of his thoughts on storytelling.

He admitted that it had never occurred to him to try to reframe the original in the increasingly popular graphic novel format. And he was skeptical when Squarzoni, a man he’d never met, wrote him to pitch the idea. Would the artist be able to do justice to such a project? Did he understand the significance of honoring the facts of a story that is, after all, nonfiction, with many of its characters still alive? Was he tenacious enough?

Squarzoni demonstrated such obsession for detail and passion for the book’s setting and characters in the texts and emails the two exchanged — they have yet to meet in person — that the idea swayed Simon, then drew him in.

“With each chapter, he’d ask me a long list of questions about things I had taken for granted, things that weren’t important in writing prose,” the author laughed appreciatively. “Obviously, when you’re writing a visual novel like he was, it matters who wears a shoulder holster and who doesn’t, what a Chevy Cavalier looks like, and whether Dave Brown wears a tie clasp or not.”

In the late 1980s, Baltimore detectives drove Cavaliers, which were government-issued vehicles; Brown was a member of the squad. Both are depicted in great detail.

At times, Simon contacted surviving members of the homicide squad, such as Terry McLarney, a detective sergeant who is a central character in the book and the last member of the team still employed by the Baltimore Police Department.

“I’d say, ‘Terry, I don’t remember this, maybe you do,” Simon remembered. “Sometimes he did, other times he didn’t. But, because he was so dutiful, I tried to answer all of [Philippe’s] questions.”

As the pair worked in this vein, a version of “Homicide” emerged, with a pared-down storyline, a matter-of-fact tone, much of the original dialogue, and a black-and-white color palette (save for the reds used to depict blood) that feels more 1940s film noir than full-fledged Simon-style verite.

It’s a far cry from the treatment the author gave the original story — Simon described his approach back then as “stand-around-and-watch” — but he found the end result to be uniquely invigorating and fully worthwhile.

“I read it like a new book, like a new narrative creation,” he explained. “It feels different than the book, and that’s as it should.”

The author compared the process to one he has been working on for years: transforming long prose works into dramatic television.

Some aspects of communication will inevitably be lost as new ones are adopted, he says, and those attempting to “perform surgery” in this manner must keep this in mind.

“You can’t replicate a book in another form,” he explained. “You [screw] it up if you do.” You’re too close to what’s already there to come up with something new. So I got out of Philippe’s way as one of the things I did for him.”

Simon incorporated numerous other ideas into his half-hour presentation and the subsequent question-and-answer session. He claims that the retirement of an older generation of homicide detectives has contributed to the city’s rising homicide rate (there were 234 killings in 1988 compared to 333 last year, and the population has shrunk by nearly 20%). It doesn’t help that cops are paid more for making multiple arrests for minor offenses like street-corner dealing than for apprehending a single murderer.

It was all good fodder for guests like the Tivvis family of Carney, who arrived early enough to secure seats in the second row.

Joe Tivvis, an attorney, his wife, Aileen, and their daughter Julia, 22, a college student and bartender, are “The Wire” fans who said they hoped to get a copy of the new book signed for Julia’s sister, who couldn’t make it.

Rodney Davis cradled his two new copies a few rows back. He took a few moments to reminisce about his days as an extra on Simon’s shows, including as a gun seller, a bartender, and a dead body, and even about the time he broke his thumb (and puked) during a shoot.

“I’ve never felt that kind of pain, but of course I’d do it again,” he said.

As Simon chatted with fans afterward, the line for autographs was long. He smiled as he signed Tivvis’ book, among others, and then did the same for Davis.

The former bit player paused before walking out the door, holding his two copies close to his chest. “He remembered me,” he explained.