Restorative justice can be cheaper and more effective than jail time at preventing reoffences. An innovative Philadelphia program for youth has a 100% success rate.

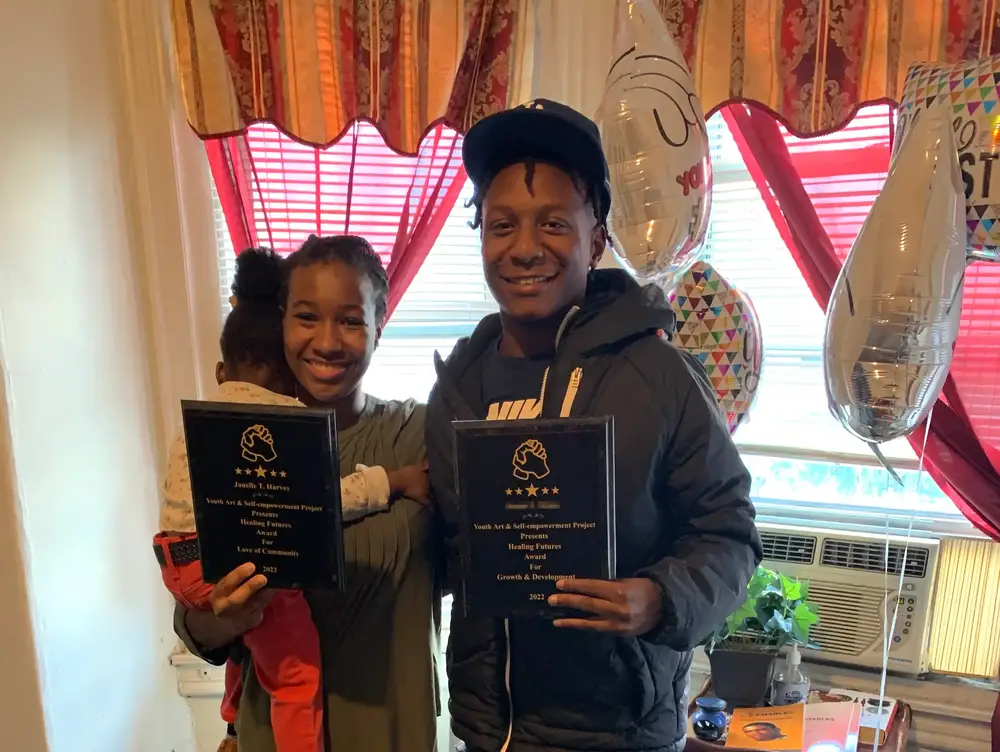

Janelle Harvey (left) and Daniel (right) after completing Healing Futures’ restorative-justice-diversion program.

Janelle Harvey was running errands in Philadelphia in March 2021 — the busy sort that come with being a new mother.

Her 1-year-old daughter was waiting for her at home, and she was anxious to get back. As she descended onto the SEPTA public-transit platform, she felt a kick. She spun around and chased the person running from her. Before she knew it, she was surrounded by five people. Some of them landed blow after blow on her in the random attack.

A week later, when she went to identify the people who caused her harm, her heart sank as she plucked out the faces she knew.

“I felt a bit of PTSD recognizing one of the faces, but I was more bothered that they were so young,” she said.

Harvey got a call a few weeks later from Kempis “Ghani” Songster, the program manager for Healing Futures, Philadelphia’s first pre-charge program for youth restorative-justice diversion. It had just launched at the Youth Art & Self-empowerment Project, a youth-led organization working to end youth incarceration. He asked if she wanted to participate.

Harvey, now 33, hadn’t heard of restorative justice. It’s a kind of program that seeks to heal and amplify community bonds by putting those who caused harm face-to-face with those they harmed, rather than thrusting them into the justice system. It is, at its core, about owning accountability. And it’s becoming more common, with programs in Chicago, Washington, DC, and the Bay Area aiming to rewrite the justice process.

Healing Futures works with youths via the Philadelphia district attorney’s office. If they complete the program, the charges against them are dropped. Harvey agreed to participate.

Restorative-justice studies find lower rates of recidivism

Here’s how Healing Futures works: Over a period of weeks, the youths meet with program leaders to talk about their needs and what accountability is and to draft an apology to the person they harmed.

At the restorative community conference, the person harmed shares how the event affected them, and the person who caused harm reads their apology.

The room, including family and community members, then decides how the youth is going to repair that harm, such as with volunteering.

Once the youth completes that plan, Healing Futures holds a community gathering to welcome them back into the fold as a productive member of society. It can take about 10 months total.

From left: Felix Rosado, Kempis “Ghani” Songster, and Queen-Cheyenne Wade of Healing Futures.

Since its launch in 2021, 33 youths have completed the program. It’s a small but impactful group: Restorative-justice diversion has been found to lead to a lower rate of recidivism and is less expensive than imprisonment.

A 2017 study by Community Works West, an Oakland, California, nonprofit focused on justice reform, found young people who completed its restorative-justice program were 44% less likely to recidivate, compared with similarly situated probation youths. And in Alameda County, where the study was conducted, it cost on average $4,500 per youth who passed through the program compared with the $23,000 a year it cost on average to put a young person on probation.

For Songster, restorative-justice practices confront harm and what drives someone to cause it more meaningfully than imprisonment does.

“We see now more than ever that the system is hard on people but it’s soft on crime,” Songster said. “The way it promotes more crime and more harm is antithetical to accountability. It lets people off the hook by occasionally throwing them away and never encouraging them or supporting them to face those inner demons or those fallibilities that led to them doing certain things.”

None of the youths who have completed the Healing Futures program have recidivated, he said.

Restorative justice lets life continue, with accountability

Daniel, 17, whose last name is being withheld because he is a minor, is one of the teenagers who approached Harvey in the SEPTA station. He’s also now one of the 33 youths who’ve completed the Healing Futures program.

He’s learning about financial literacy and dreams of starting his own clothing brand. He works at a movie theater and, he said, has learned how to be a leader in his community.

As part of his plan, Daniel was asked to volunteer four hours a week for six months at the Charles Foundation, a Philadelphia nonprofit that teaches conflict-resolution skills and advocates against gun violence. Daniel ended up volunteering for seven hours a week. A year and a half later, he still volunteers there.

Daniel said coming face-to-face with Harvey and learning about her desire for him to grow beyond his lifestyle helped push him to succeed.

“I learned don’t try to impress the people you want to impress. Impress the people you got to impress. And just be yourself,” Daniel said. “Don’t let anybody tell you not to be yourself. Because you being you is the best you.”

‘The investment in their lives can take us further as a city’

Kendra Brooks, a council member at large on the Philadelphia City Council, said Healing Futures was a step in the right direction for the city.

Brooks has been a trained practitioner of restorative-justice techniques since 2015 and has brought its teachings into the schools of her children. Still, she said, the lessons are often coming too late.

“My daughter’s buried more friends than I have in my lifetime,” she told Insider. The number of gun-violence victims in Philadelphia who are youth has grown since 2015 to nearly 10%.

Kendra Brooks has been a trained practitioner of restorative-justice techniques since 2015.

Healing Futures is referred only certain kinds of cases by the district attorney’s office, including assault, arson, and theft. The program isn’t referred killings or drug-related cases. Still, Brooks said it was mending communities. She said she’d love to see it go deeper and have restorative-justice teachings introduced early on in the Philadelphia school system.

“As much money as we spend to incarcerate a young person, the investment in their lives can take us further as a city,” she said. Increasing the reach of Healing Futures, and other restorative-justice practices, can allow young people to return to their communities and “be healers themselves,” Brooks added.

Healing Futures’ staff is a testament to this. The family of Queen-Cheyenne Wade, a facilitator, has been splintered by incarceration. Songster and Felix Rosado, a coordinator, were turned on to restorative justice while incarcerated.

Rosado started last year after serving 27 years of a life-without-parole sentence.

“I jumped into this job immediately,” Rosado said. “It gives me the opportunity to go back in time and talk with my younger self. Who knows, had I had an opportunity to participate in something like this, where my life could have went.”