The Social Security curveballs making retirement even more confusing

Two provisions reduce Social Security benefits for retirees if they worked both private- and public-sector employment.

Patrice Earnest, 66, expected to have much more money for retirement. But after her husband died, she checked her Social Security survivor benefits. The total: $0.

“It’s absolutely stunning,” Earnest said. “My husband worked all his life since he was 16 bagging groceries, and that Social Security was something we had planned to have in our retirement.”

Earnest won’t see a penny of the benefits her husband worked for — and it’s due to her work history, not his. She’s one of a few million Americans who see cuts to either their own Social Security benefits or to their survivor benefits when a spouse dies because they have a career history that includes both government and private sector jobs.

The idea is to ensure public servants with pensions don’t get overly generous retirement benefits, keeping people like Earnest from receiving full benefits from both a government pension and Social Security. But like many people affected by this, Earnest was caught by surprise — throwing her retirement budget for a loop.

We want to hear from you. Are you an older American with any life regrets that you would be comfortable sharing with a reporter? Please fill out this quick form.

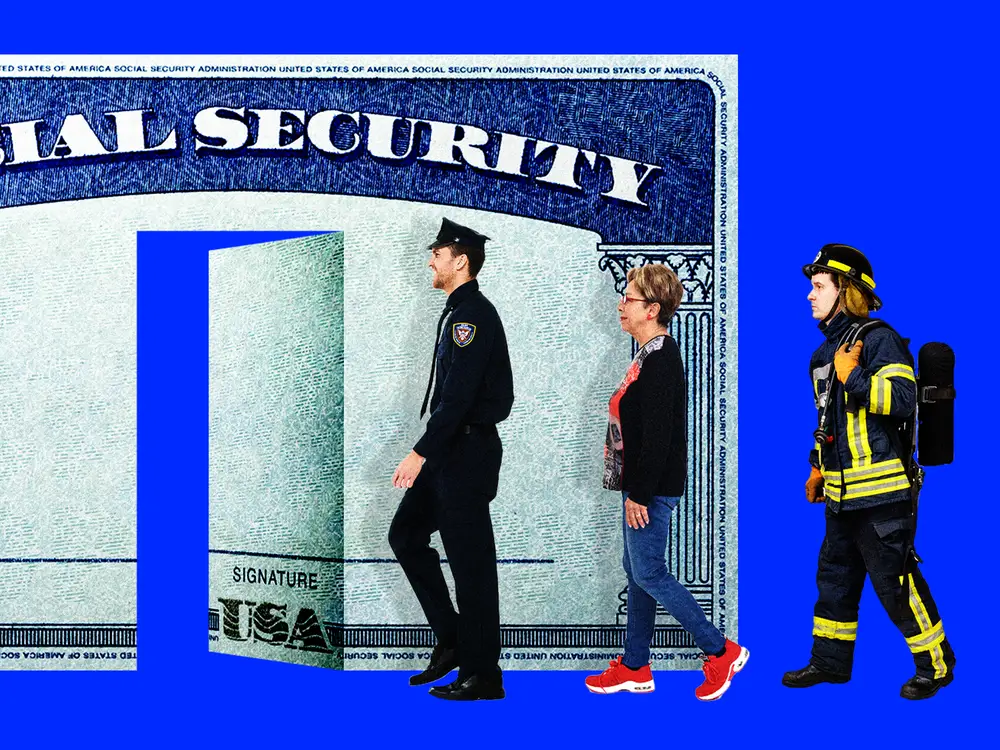

The two provisions at play here are the Windfall Elimination Provision and the Government Pension Offset, or WEP and GPO for short. They typically affect middle-class workers in select states who spent some time in a public-sector job, such as teachers, firefighters, and police officers, with government pensions and no Social Security taxes. The measures reduce Social Security benefits accrued during private-sector work to compensate for the state or local government pension benefits.

Even a short time with a pension can trigger cuts to Social Security that workers might have earned in a private sector role. WEP reduces a worker’s own Social Security benefits, while GPO applies to spousal or widower benefits like those Earnest expected to collect.

“Certainly, I could use the extra money owed to me to pay the bills that I thought we could with a two-income household,” she said.

Right now, the provisions are part of a political firestorm over how the US should care for its older workers, with Social Security already imperiled and many retirees struggling to pay their bills. On September 19, a bipartisan bill to eliminate WEP and GPO received the number of signatures needed for a vote in the House.

While supporters of WEP and GPO say they’re necessary for ensuring equity, critics say they’re applied unevenly across states and professions, sometimes resulting in benefit calculation mistakes. Those advocating for eliminating the provisions say they also hurt middle-class government workers the most.

Unpredictable cuts to Social Security benefits make it impossible to plan for retirement

The provisions can end up slashing your Social Security payments by up to half if you have a government pension, whether you were planning on survivor and spousal payouts or your own checks from time spent in the private sector. Workers with a private-sector 401(k), on the other hand, are not barred from collecting full Social Security.

Jane Roth, 74, a widow in New Haven, said she may have reconsidered becoming an educator if she had known about the provisions. Roth worked in the private sector, took time off to raise children, and then worked as a public school teacher.

She’s still teaching and has another 14 years before she can receive her full pension. In the meantime, she can’t afford to live off the $8,000 she gets annually through her late husband’s Social Security survivor benefits. If she retired and started receiving her pension, she’d get even less because the GPO would kick in and zero out her survivor benefits.

“What are my choices? Do I retire with a partial pension and lose 100% of my Social Security survivor benefits, or do I work until I am 88?” Roth said. “We are not asking for a handout. This is our money. They took our money and said this will be waiting for you upon retirement, and it’s not.”

WEP and GPO were instituted in the 1980s to make retirement income more equitable, as many believed workers with government pensions had an advantage over Social Security recipients. But even pensions have become less of a sure economic bet, with returns less funded and many states cutting back the benefits they offer to teachers.

“Essentially, it’s a substitute,” Karen Smith, a senior fellow at the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute, said. “The reason they don’t pay Social Security is because they have this alternate pension.”

Today, however, major criticisms center on the uneven application, rampant errors, and poor communication with those impacted. WEP and GPO impact teachers in 15 states, while state, county, and municipal employees are penalized in 26 states. An audit by the Office of the Inspector General for the Social Security Administration found that WEP and GPO were two of the “leading causes of improper payments” in the system.

According to a 2013 paper, the WEP reduces benefits disproportionately for lower-earning households in some cases. The Bipartisan Policy Center wrote in a July paper that limitations to WEP calculations resulted in “an imprecise approach to adjusting Social Security benefits.”

Many who support WEP and GPO, whether in their current or modified forms, say the math still has merit, as those affected by the provisions tend to be better off. The Social Security Administration reported the average monthly check as of July 2024 is about $1,783. Meanwhile, nearly half of WEP-affected Social Security beneficiaries had pensions above $3,000 a month in 2023.

Proponents of the provisions argue that because of how Social Security calculates benefits, a worker who spent a short period of time in the private sector and the rest of their career working toward a public pension could end up getting a proportionally larger Social Security benefit than a worker making the same amount of money in the private sector for their whole career.

Additionally, canceling WEP and GPO could worsen Social Security’s financing, moving the depletion date for funds from 2035 to 2034 or sooner. According to the Urban Institute, this could disproportionately benefit those with higher incomes who have 401(k)s or other private retirement accounts.

But some of those workers on the other end of the provision disagree.

“I had a 76-year-old lady call me up. She taught for 40 years and retired, but recently her husband passed away. She lost all his earned benefits, and she’s going to wind up either selling her house or look for a part-time job,” said Janis Hernandez, a retired teacher in Louisiana, who sits on the communications committee for The National Task Force to Repeal the WEP and GPO.

The future of WEP and GPO

The Task Force notes that 83% of those penalized by the GPO are women, many of whom took time away from their careers to raise children and thus have less in Social Security than their spouses. Many impacted by the GPO also can’t fully calculate their reductions until their spouse dies, like Earnest.

Critics of the programs also note that there is no similar means testing for private-sector retirement plans.

“If somebody is in the private sector and they’ve got a good 401(k), you don’t tell them, ‘Oh, we’re not going to give you your Social Security,'” Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Republican who’s focused on Social Security solvency, told B-17.

WEP and GPO are front and center in Congress this month when the House of Representatives votes on the bipartisan Social Security Fairness Act, which aims to eliminate both provisions.

An alternative to eliminating the provisions completely is simplifying the formula for calculating Social Security benefits, which the Bipartisan Policy Center found would be less costly over time.

As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities finds, there’s “widespread support” for a more proportional formula to calculate the amount these provisions shave off. But right now, any action on Social Security or altering those provisions may be a long shot, especially with the presidential election looming.

Anne McLeod, 68, said the provisions can be punitive.

In her 20s, McLeod worked various part-time and lower-paying clerical roles, all of which paid into Social Security. She then taught in New Orleans for 28 years and worked part-time jobs after school hours.

She’s retired now and gets $67 monthly in Social Security — $500 less than she would’ve gotten sans WEP. She gets $2,910 monthly in state retirement, and she creates and sells artwork for extra income. While she and her husband are up to date on their bills, they simplified their lives by selling their house and renting because it’s cheaper.

“It’s almost like a punishment in a way because we chose to be educators or firemen or policemen,” McLeod said. “They said you get a good enough retirement from the state, so you’ll be OK not getting all your Social Security.”