Dockworkers went on strike at the worst possible time

Tens of thousands of longshoremen are on strike.

Tens of thousands of dockworkers are on strike after the International Longshoremen’s Association and the US Maritime Alliance, which represents dozens of East and Gulf Coast ports, failed to reach consensus on a new labor contract.

The walkout is set to shutter 36 ports in the region, according to the Associated Press. These ports handle about half of all US ocean imports. Estimates of the economic fallout vary — The Conference Board analysis estimates that closing them for just a week could cost the economy $540 million per day, while JPMorgan analysts put the figure at between $3.8 and 4.5 billion, in a note issued September 26.

The union is demanding 77% pay raises over the next six years to keep pace with inflation, a figure that would still put them below many of their West Coast port worker counterparts, according to CBS News.

The strike comes at a critical economic and political moment: roughly one month out from the US presidential election, as consumers and businesses alike begin to feel relief from recent inflation, and just ahead of the busy holiday season.

And it comes just after Hurricane Helene, which killed more than 100 people and left devastation across several states, including widespread flood damage that could leave cities like Asheville, North Carolina, without running water for weeks.

The flooding and debris have made many roads and highways across the Southeast impassable, or at least tricky to traverse, adding to supply-chain pressures.

Big hits to small businesses

While there was a sliver of hope that a contract could be reached after both sides exchanged wage offers on Monday evening, the groups were ultimately unable to reach an agreement, with automation and wages being the major sticking points throughout negotiations.

Consumers aren’t likely to feel an immediate effect in their pocketbooks, two supply chain experts told B-17, but the strike will likely cause major delays and disruptions for everything from food items to auto parts.

The strike had been brewing for months following increasingly aggressive relations between both sides.

As a result, most large retailers have had the time to prepare, stock up their supply chains, and place their holiday orders early, said Brian Pacula, a supply chain partner at West Monroe consulting firm.

“The Fortune 100s — your Walmarts and even Home Depots — are probably going to be fine,” Pacula said. “They generally have very mature supply chains.”

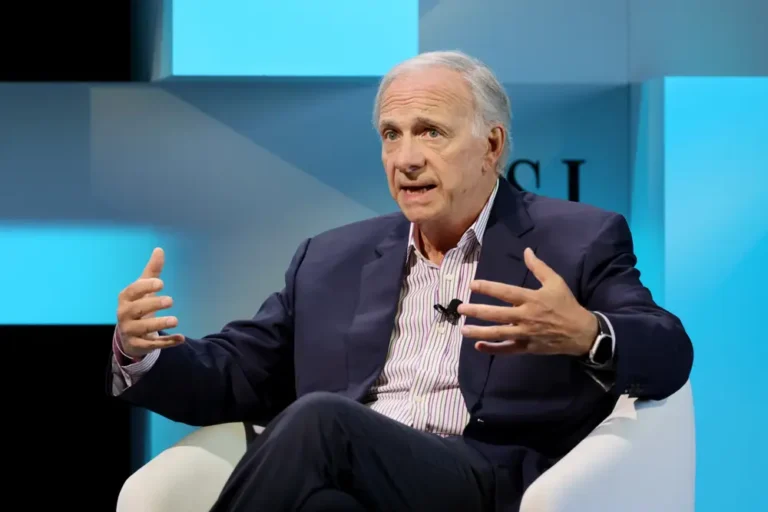

Mid-size and smaller businesses, however, will likely bear the brunt of the walkout, especially those waiting on shipments from Europe, said Michael Yamartino, CEO of post-purchasing company Route. Rerouting items to the West Coast will cost businesses time and money.

“Since these are ports on the East Coast, the folks who have suppliers in Europe will be hit,” Yamartino said. “The auto industry is high on that list.”

Trade groups have called on President Joe Biden’s administration to help negotiate a deal, but the looming election complicates government involvement.

Over the weekend, President Joe Biden, who has modeled himself as a stringent supporter of workers, said he had no plans to step in and stop the looming strike. The International Longshoreman’s Association previously said they didn’t want government intervention and preferred to negotiate independently, according to the Retail Industry Leaders Association.

Under the Taft-Hartley Act, the president has the power to seek a court injunction that would trigger a back-to-work requirement while the two sides continue negotiations should the walkout affect national security.

But if the strike lasts longer than a few weeks, Pacula said he expects the federal government to get involved, regardless of the election implications.

“It will be crippling for our economy,” Pacula said. “This can’t go on for too long.”