Fears of automation are at the heart of the dockworkers strike

Dockworkers picket near the Port of Miami entrance and demand a new labor contract.

Striking dockworkers at US ports say they’re worried that jobs could plummet as shipping companies increasingly turn to automation.

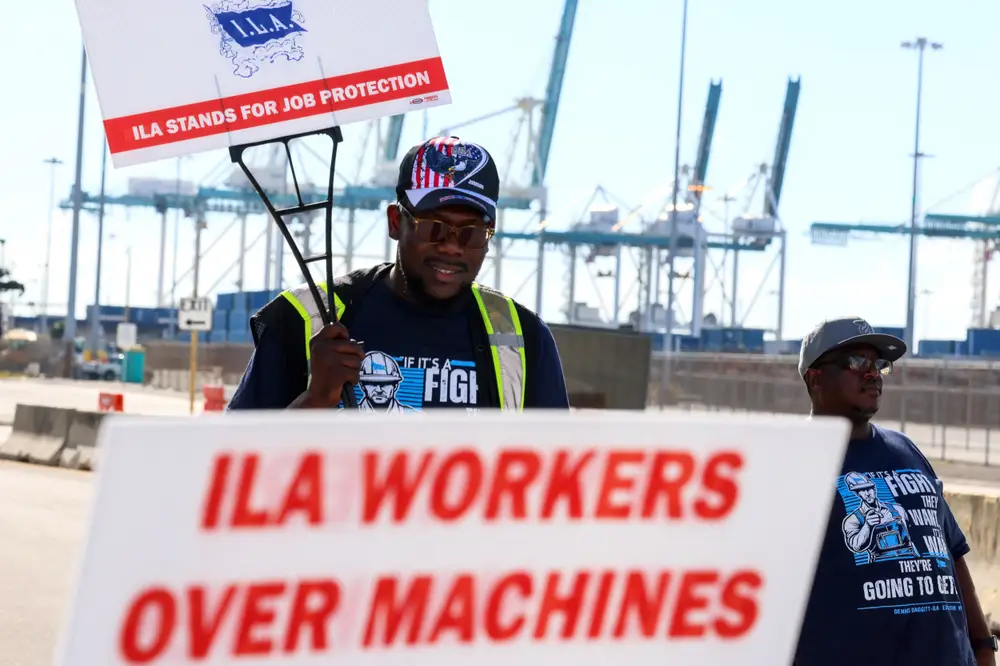

Picketing workers gathered at ports in New York and Miami carrying signs reading “Machines don’t feed families” and “Fight automation, Save jobs.”

Their concerns have thrust automation to the core of the current stand-off between the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), the union representing the tens of thousands of dockworkers on strike at 36 eastern US ports, and the US Maritime Alliance (USMX), which represents their employers.

USMX called the strike “completely avoidable” in a statement Tuesday, and said it “strongly supports a collective bargaining process that allows us to fully bargain wages, benefits, technology, and ensures the safety of our workers.”

The union’s objection to the way shipping companies are using automation now is a key sticking point in the negotiations for a new labor contract.

Earlier this summer, ILA President and chief negotiator Harold Daggett said that one of USMX’s major companies “continues to violate our current agreement with the sole aim of eliminating ILA jobs through automation.”

For its part, the employers association has said it is willing to renew the existing contract terms regarding the use of new technology.

USMX said in August that its most recent offer at the time retained “the existing technology language that created a framework for how to modernize and improve efficiency while protecting jobs and hours.”

The ILA didn’t respond to a request for comment from B-17.

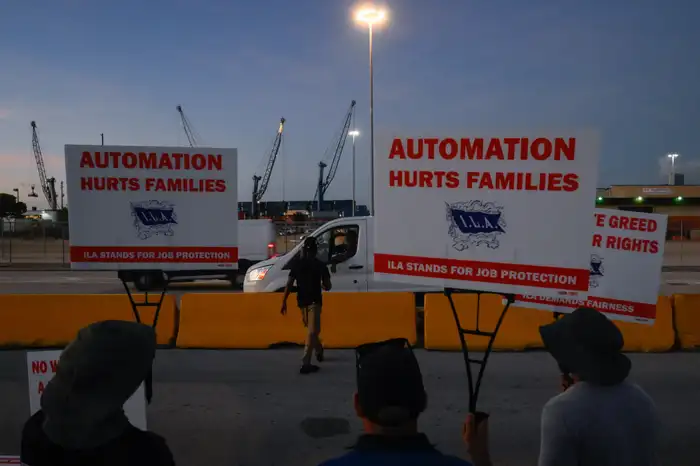

Port of Miami workers, holding banners, gather early in the morning to begin the strike on the East Coast on October 01, 2024.

Under the labor contract that expired Monday night, “no fully-automated terminals developed and no fully-automated equipment” is allowed, and partially automated equipment is only allowed after an agreement is worked out regarding workforce protections.

The contract further requires a review of “new work” arising from technology, as well as training and reassignment opportunities in a manner that preserves union labor hours.

But negotiations broke down over the summer when the union said that a gate at a facility in Mobile, Alabama, was allowing trucks to enter without the involvement of union workers, violating the contract.

The union accused Maersk Line and APM Terminals of trying to circumvent the automation provisions in the contract and said it would not return to the table with USMX until the matter was resolved.

“We will never allow automation to come into our union and try to put us out of work as long as I’m alive,” Daggett said in July.

A spokesperson for Maersk and APM Terminals did not respond to a request for comment.

The move eventually contributed to the ILA earning the unusual distinction of being a labor union being named in an unfair labor practices complaint filed by management.

Automation is already transforming the supply chain and reshaping jobs, though it’s arriving more slowly to Eastern US ports than to other ports around the world as container volumes continue to swell.

Stephen Edwards, CEO of the Port of Virginia in Norfolk, told The New York Times in September that semi-automated operations enabled his facility to handle surges during the pandemic and after the Baltimore bridge collapse.

In spite of the now-expired contract’s provisions for semi-automated technologies, Daggett said in a September 7 letter that “the ILA does not support any kind of automation, including semi-automation.”

And while the first hints of movement in the months-long stand-off came just hours before the strike Monday night, with the USMX raising its wage increase offer to nearly 50%, the debate around automation’s place at US ports remains unresolved.