A major curveball in retirement preparedness: divorce

A decade ago, Libby Mintzer imagined her retirement.

Her gated community would sit along a river, each house hugged by palm trees and Florida coast humidity. Mintzer planned to spend mornings at yoga class and evenings on the deck with her husband, watching the sun set in pinks and oranges from their rocking chairs.

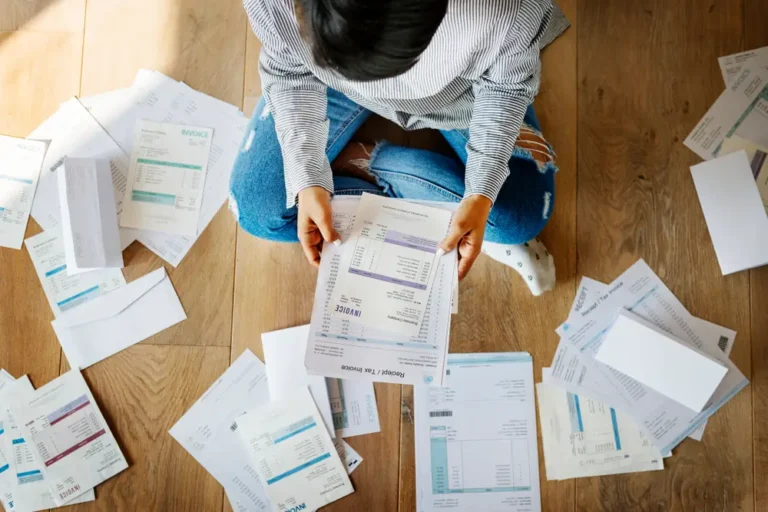

Today, the 73-year-old lives alone in Tampa and receives $1,600 monthly Social Security income. When Mintzer and her husband divorced in the early 2010s, she lost all assets — the house on the river and any shared investments — and doesn’t receive any spousal support. She drained most of her savings in her 60s when she cashed out the few thousand dollars in her 401(k) to fund her then-husband’s business venture.

“I always thought of everybody else before me,” Mintzer said. “And I would tell any woman now: ‘Don’t do it.'”

Although Mintzer used her $200,000 in settlement money to buy and furnish a one-bedroom apartment, she’s barely able to keep up with the rising HOA fees. She said she has maxed out her credit cards to pay for groceries, and she’s scrambling to apply for part-time jobs but isn’t having any luck landing roles.

It’s a painful departure from her married life. Mintzer had a 30-year career as a paralegal and was often the main household income earner with her six-figure salary. She had worked hard to ensure she and her husband would be comfortable as they aged.

Millions of Americans are feeling financial pressure in retirement. Monthly Social Security checks aren’t enough for most baby boomers to get by, further fueling a retirement crisis. And boomers are experiencing a newer phenomenon that adds to their financial distress: More are getting divorced later in life.

A 2022 study published in the Journal of Gerontology found that, from 1990 to 2010, the divorce rate for adults 65 and older has nearly tripled; among adults ages 50 to 64, the divorce rate per 1,000 rose from 4.85 in 1970 to 12.72 in 2019.

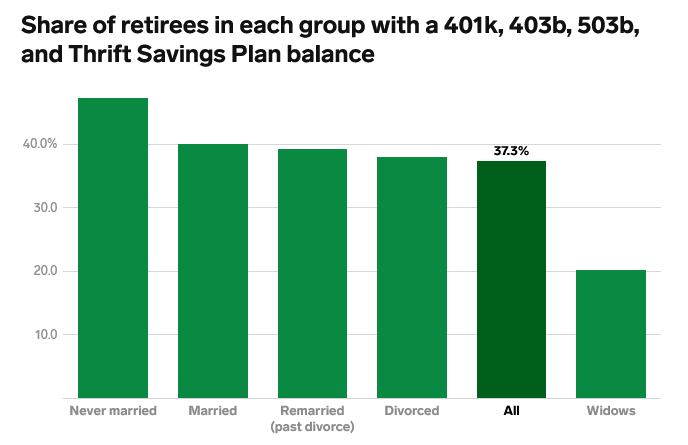

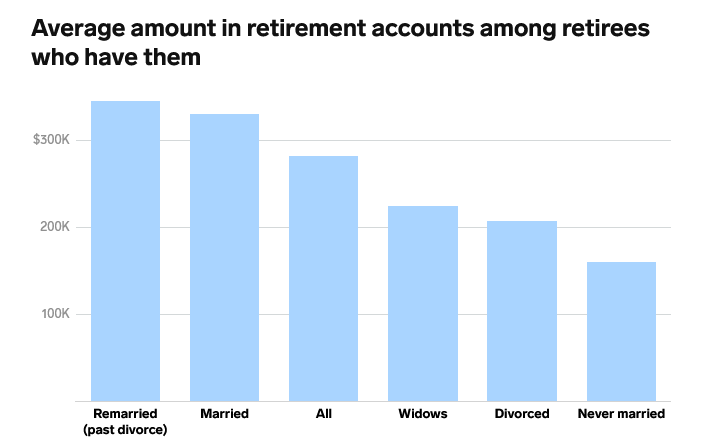

Divorcees have lower average 401(k) balances, less savings, and a more limited monthly retirement income than married people, according to a B-17 analysis of individual-level data from the Census Bureau’s 2023 Survey of Income and Program Participation. Those numbers undergird the reality that an increasing number of middle-aged and older Americans are facing: The reverberations of their divorces will be felt long into their golden years.

For retirees like Mintzer, this can leave them struggling to survive.

“I cannot live with just Social Security,” she said. “I don’t have any money to live on.”

Most married couples’ retirement savings are tied together

In many ways, the world is built for married people: Taxes and living expenses are cheaper for two. Married couples also often share a household income, savings, assets like real estate and investments, and custody if they have children. But all of that gets divided up in a divorce.

To be sure, the divorce rate has been steadily declining for years. According to the CDC’s analysis of 45 states, the divorce rate was around 2.4 per 1,000 Americans in 2022, down from around 4 per 1,000 in 2000.

Still, a couple’s retirement assets might feel the damage of a breakup. The average married retiree has over $100,000 more in their 401(k) and savings accounts than a divorced retiree. This might be because settlements caused retirees to split or completely lose access to the accounts, said Melody Evans, a vice president wealth management advisor at TIAA, a retirement and wealth management firm.

Indeed, there are ways to protect assets from divorce. A prenuptial agreement can be helpful, but it typically doesn’t protect wealth built after the couple ties the knot, like retirement savings.

Talking about money as a couple — and understanding joint assets — is one of the best ways spouses can protect themselves during a divorce, Evans said.

To preserve retirement savings, she said couples can also split their 401(k) and Roth IRA funds, or take Social Security based on the higher-earning spouse’s salary.

Evans added that if one person in a relationship is in charge of banking and major purchases, the other spouse might be in the dark about their household’s financial situation.

“When I hear about people having a really hard time or feeling like they missed assets during a divorce, generally, it’s because they were not fully aware of what assets the couple had,” Evans said.

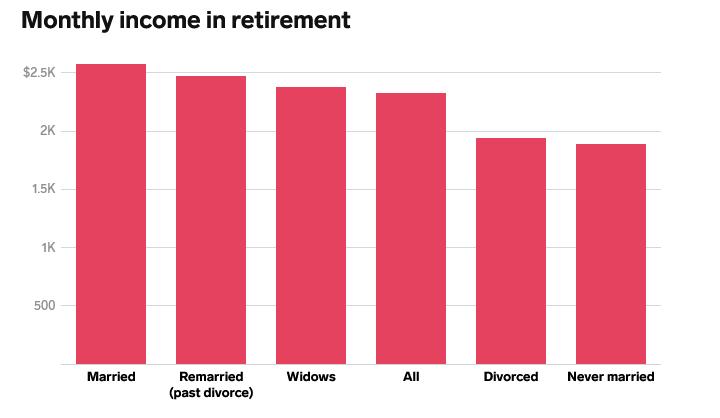

This division of wealth in a divorce — and financial literacy gaps — can have major consequences. B-17 analysis found that the average income of a married retiree is $2,577 a month, considering money they might receive through pensions, Social Security, retirement accounts, and insurance benefits.

A divorced retiree, however, takes home $1,940 a month. This compares to retirees who were never married ($1,887 monthly), people who are widowed ($2,381 monthly), and people who remarried after a divorce ($2,476 monthly).

Women can be especially vulnerable to lost assets and savings

While divorce can impact anyone’s retirement plans, some demographics are more vulnerable to lost assets and savings. For example, Evans said some women might not have a strong financial infrastructure compared to men — women couldn’t have their own credit cards until the mid-1970s, and it was more common for baby boomer women to be stay-at-home-parents, or hold primary domestic responsibilities.

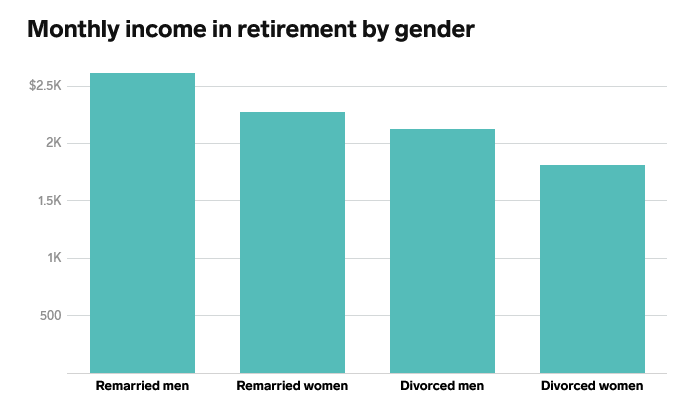

Evans said that these traditional gender roles could contribute to long-term income differences. America’s gender pay gap also means women might earn less than men for the same job.

“There is generally a disparity in terms of how much one person has saved into a retirement plan versus the other,” she said. “Maybe that’s because one spouse didn’t spend as much time in the workforce, maybe they helped in the households differently.”

On the whole, according to B-17 data analysis, retired women’s finances fall behind men. Men’s monthly retirement incomes are nearly $600 more than women’s — $2,610 to $2,042 — and they’re more likely to have a balance in a retirement account. Among retirees with retirement accounts, men have, on average, $318,727 socked away, regardless of marriage status. Women have $239,706.

Kathryn Clark got married as a teenager and raised her sons in California’s Bay Area. After Clark finished her GED, she worked a series of roles in the accounting, healthcare, and tech industries — and was oftentimes the main household income earner.

When Clark finalized her divorce around the time she turned 50, she had been married for three decades. Neither she nor her husband had strong retirement savings, and they sold their house a few years before they split because they could no longer afford it. Clark didn’t leave the relationship with any money or assets. She did, however, become the sole parent financially providing for their children. Clark’s youngest son was still a teenager when the divorce was finalized, and she had to spend all the money she had to support herself and her kids.

“When the divorce came, I had nothing,” she said. “I just walked away with half of what was in the bank account — which couldn’t have been more than a couple hundred dollars.”

Now 80 years old, Clark lives near the Bay Area in a low-income housing unit. She lives check to check on Social Security, has no savings, and struggles to afford groceries on just $23 a month from SNAP. When Clark’s ex-husband died a few years ago, she learned that she could receive an extra $400 monthly based on his Social Security contributions. She had previously been trying to get by on less than $1,000 a month.

Overall, divorced women like Clark see lower monthly retirement incomes than their male counterparts — and peers who have remarried. Divorced women, on average, have around $1,800 a month in retirement income, while divorced men receive nearly $300 more monthly, per B-17 analysis.

To protect themselves, Evans said people should invest early in understanding their full financial situation, a task she said wealth advisors can help with. One of Mintzer’s greatest divorce regrets is that she didn’t safeguard her retirement savings.

“Don’t rely on someone else — whether it’s a husband or wife or children,” Mintzer said. “From the day you turn 18 and you start working, start preparing for that day when you’re not going to be working anymore.”