The Fed is repeating the same mistake that caused a decade of slow growth and high inflation in the 70s, according to one financial historian

Investors rejoiced at the Federal Reserve’s 50 basis-point cut and last Friday’s expectation-beating jobs report.

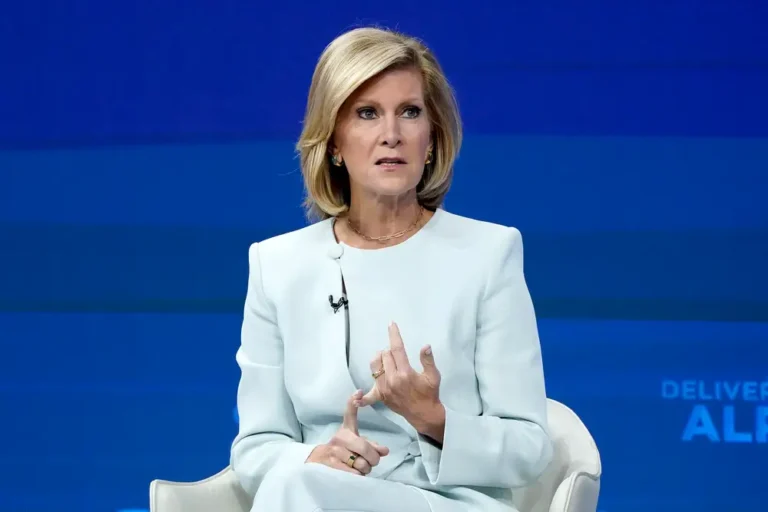

But Mark Higgins, a financial historian and senior investment advisor at Index Fund Advisors, doesn’t see much reason to celebrate.

Higgins believes the Fed made a mistake by cutting rates at all, much less by 50bps. The economy hasn’t defeated inflation yet, and cutting rates will only make inflation worse, he said.

“The Fed is making a mistake because the risks of inflation reigniting and the consequences of that are much higher than if it stayed tight too long,” Higgins told B-17.

The inflation battle isn’t finished yet

To Higgins, one warning sign that inflationary pressures remain was the September jobs report, which beat expectations and signaled the labor market may not be cooling off as much as the market initially thought. Then there’s rising wages. Hourly wages are up 4% year-over-year, and while that may seem like a positive development initially, it could actually be hinting at runaway wage inflation, Higgins said.

The Fed’s aggressive signaling of a soft landing is also inflationary, Higgins said. The promise of rate cuts lifts consumer confidence and fuels spending. Lower rates are boosting demand for homes, and people will spend more in other places as well because they’re paying less on their mortgages, according to Higgins.

Unfortunately, inflation is notoriously hard to quash. If the Fed is serious about extinguishing inflation, it needs to implement stringent tightening policies. In Higgins’ view, it’s better that the Fed overcorrect with quantitative tightening than the other way around.

“If you let go too early, it springs back up,” Higgins said of inflation. “And that’s why you have to go too far in the other direction.”

It’s a tough pill to swallow, but this course of action often leads to an economic downturn. “If you don’t extinguish inflation decisively, which often requires a recession, it’s going to pop back up at a higher level,” Higgins said.

History repeats itself

Similar scenarios have happened twice before, according to Higgins — once in the 1920s, and again in the late 1960s.

In the 1920s, the economy was coming out of World War I and an influenza pandemic. Pent-up demand from the pandemic and the transition back to a peacetime economy sent inflation surging, and the Fed was only able to get inflation under control after raising rates aggressively and causing a recession.

In the 1960s, inflation began creeping upward again due to excessive money supply growth, towering deficits, and external supply shocks. This time, the Fed was more concerned about lowering unemployment instead of taming inflation and didn’t tighten as stringently, leading to what became known as the Great Inflation of 1965 to 1982. The 1970s were plagued by slow economic growth, rising prices, and soaring unemployment. Supply chain issues contributed further to soaring prices in the energy sector.

This period of stagflation ended only when Paul Volcker initiated a strict rate-hiking campaign by raising interest rates to 20%.

There are some unsettling similarities between now and back then. During both the 1920s and 1960s, wages didn’t keep up with the cost of living, resulting in a surge in strikes. Supply chain issues also amplified the economic downturn. Higgins points to the recent dockworkers strike as a potential indicator of worsening wage inflation.

Battling inflation

Higgins suspects that the Fed will repeat the same mistakes it made in the 1960s by cutting rates too quickly and causing inflation to spike again.

And if history proves correct, then the only way to fix runaway inflation is to double down on tighter monetary policy by keeping rates elevated, even if it causes a recession. Expect a slower pace of rate cuts — or even rate hikes — from here on out, Higgins predicts.

“I think the most likely outcome is that inflation will reignite, and the Fed is going to need to slow down,” Higgins said. “And I think there’s a conceivable scenario where they’re going to have to reverse course.”

Failing to address surging inflation could hurt the Fed’s credibility and hamper its ability to guide markets going forward, in Higgins’ perspective.

Higgins is keeping a close eye on wage inflation and CPI readings to see if the patterns exhibited in the September jobs report continue.

“One month is not conclusive, but that’s a concerning employment report,” Higgins said.