Inflation is scrambling Americans’ perceptions of middle-class life

Vincent, a 29-year-old medical-sales rep, makes $130,000 a year.

It was a dream when he was younger — once he was making six figures, he assumed he’d be in financial nirvana, worry-free, off on vacation somewhere at least once a year, perhaps able to buy a home in the not-too-distant future.

“I was like, if I could make six figures, I’d have a nice life. I can save up the down payment on a home and start to begin my life,” said Vincent, who requested to use only his first name to protect his privacy but whose identity is known to B-17.

He was surprised to find out that in Santa Barbara, a coastal California city where the cost of living is 65% higher than the national average, he’s barely able to save for anything, let alone buy a house, plan for kids, or hit other milestones of middle-class life.

“Bigger-ticket items that our parents could have bought, like a home or car, that is, just to me, out of reach,” Vincent said, though he acknowledged his budget could go further in a city with a lower cost of living.

“I would have to save 10K for six or seven years straight and really sacrifice to put down on maybe the dumpiest thing I could find here,” he added

Vincent’s experience is emblematic of what has become of the middle-class American dream, with many earning six figures but feeling like they’re way behind the curve or that the economic chips are stacked against them.

Some of these concerns are real — see the wildly expensive US housing market — while others, experts say, may be a matter of perception versus reality, as the economy feels tough even as earnings are growing and employment is strong.

Vincent is among a growing group of middle-class Americans — defined in 2022 by the Pew Research Center as households earning between $48,500 and $145,500 — who don’t feel they can’t afford to live a traditional middle-class life, replete with a home and a comfortable retirement.

Eoin Sheehan, a senior research analyst at Redfield & Wilton, says inflation has caused many Americans to ignore the overall strength of the US economy.

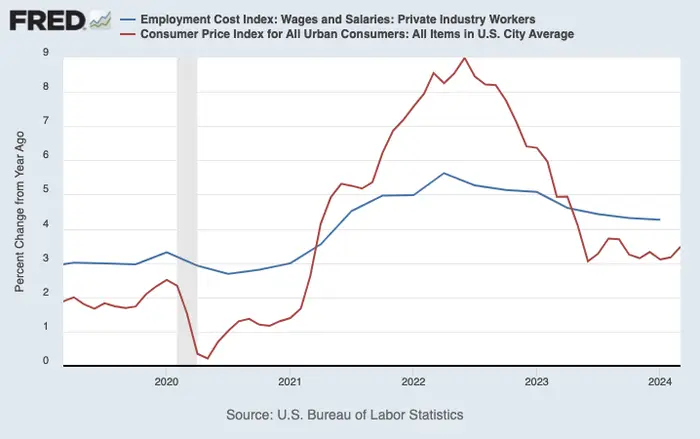

Growth, hiring, and financial markets are strong, and wage growth has started to exceed the pace of inflation.

Wage growth has started to beat the pace of inflation.

While higher costs pose challenges to retiring or homebuying, those goals aren’t out of reach with careful planning, Chris Collins, a wealth advisor at Northwestern Mutual’s Collins Financial, says.

Collins suspects that most middle-class Americans feel anxious about their financial situations because of financial-shock fatigue — the exhaustion of navigating one big economic shock after another — as well as a lack of planning.

His clients typically start to calm down once they crunch the numbers and figure out how much they need to save for retirement or to meet their other financial goals. Before that, many falsely assume they need to work forever, he said.

“I’m not telling people, ‘You are going to die broken and alone.’ It’s, ‘Hey, with a little bit of work here, you’re going to be all right,'” Collins said. “They don’t feel like they can relax until somebody runs the financial plan, runs the modeling and says, ‘You’re going to be fine.'”

Still, those statements don’t square with how many households may be feeling about their financial and wealth status. The sentiment is all over the place online, expressed by social-media users who identify as middle class but say they’re increasingly feeling less well-off.

A TikTok user in Alabama, Jessica, said she believed the middle class was dying. She pointed to her eldest daughter, who she said worked 60 hours a week during her pregnancy to provide for her family.

“Do we even have a middle class anymore, or is it just the haves and the have-nots?” Jessica said in a TikTok post in February. “Because the haves are having, and the have-nots are struggling.”

“I’m sorry, but if you know somebody with kids and they say they’re not struggling financially, they’re lying,” Kayla, another TikTok user, said. She pointed to the rising cost of groceries and other essentials.

“Honestly, life is difficult for the middle class,” Vincent said. “I feel like I can make ends meet, but I can’t really move this lifestyle.”

Cost-of-living crisis

Middle-class Americans have been feeling worse about the economy for a long time, but the negative mood appears to have jumped sharply in recent years.

A survey from Northwestern Mutual found financial anxiety had hit a record high. In a Primerica survey of middle-class households conducted in March, half of the respondents said their financial situation was “not so good” or outright “poor.”

For many in the middle class, inflation is at the heart of this feeling. In the Northwestern Mutual survey, 51% of respondents said inflation was the biggest obstacle to financial security, while 67% of households in Primerica’s survey said their income was falling behind the cost of living.

That’s making people feel locked out of many of the benefits long associated with middle-class life. Seventy-four percent of middle-class Americans in Primerica’s survey said they had cut back on nonessential spending. In a 2023 Redfield & Wilton survey conducted for Newsweek, half of Americans polled said they didn’t plan on going on a summer vacation because of a higher cost of living.

Many are also dipping into their savings, making retirement feel uncertain. In the Primerica survey, 60% of Americans said they didn’t think they were saving enough to comfortably retire.

In that survey, 46% of middle-class Americans said they’d dialed back or paused saving, and 38% said they didn’t think they could afford an unexpected expense over $1,000.

“The anxieties about things like owning their own home, going to college — all these things that the majority of Americans perceive as being sort of indicators of middle-class status — many of them now don’t think those things are attainable for them,” Sheehan said.

Buying a home may be the greatest example of middle-class life feeling out of reach for many, and that struggle is very real, rather than merely negatively perceived.

With mortgage rates hovering close to a 23-year high and home prices near record levels, Americans need to earn 80% more than they did before the pandemic to comfortably afford a home, a recent Zillow report found. First-time homebuyers, meanwhile, made up less than one-third of all home purchases in 2023, one of the lowest shares ever recorded, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Vincent said owning a home seemed out of the question for now. If he cut back on some expenses and lived more frugally, he estimated he could save up to $10,000 a year. At that rate, it would take him at least eight years to save up for the average down payment on a US home, which was a record $84,000 last year, according to data from CoreLogic.

“What part of that makes sense?” Vincent said.