Andrew Webber’s forever warHe gave up everything to fight for Ukraine. His family is still trying to figure out why.

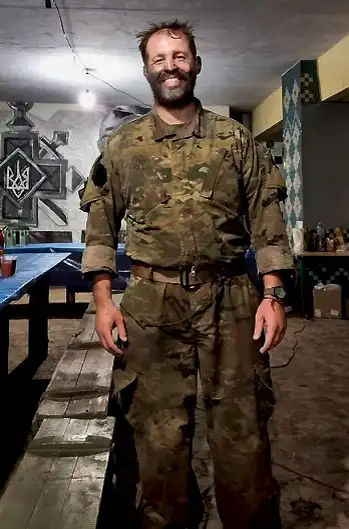

Andrew Webber during combat operations.

The American drank his beer in a center booth, bathed in garish light from the neon signs hanging over the bar. It was a weeknight in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro, and the war was raging only a few hours away. Andrew Webber had come to join it.

Dressed in his civvies, his light brown hair obscured by the White Sox cap he wore everywhere, Webber chatted with his fellow recruits in Chosen Company, a ragtag band of volunteers from all over the world, many of whom he’d just met. He was 40 years old, a successful attorney, and a father to two little girls. He was a bit out of shape, but he still had the lumbering gait of a former wrestler and a demeanor that screamed ex-military. A former Army paratrooper, he’d served three tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, earning a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. Like others in Chosen Company, Webber had been drawn to Ukraine for reasons he couldn’t quite explain. Maybe it was the injustice of the Russian invasion. Or maybe it was the fear that Ukraine could become another Afghanistan, abandoned by America and overrun by the enemy. Either way, Webber knew what it was like to fight a war and lose.

He was a world away from his comfortable life in Seattle, where he and his wife, DeeDee, owned a new three-story house in a hillside neighborhood of quiet streets and views of the city beyond. Back home, he would lay on the rug in the living room and hold up Vera, almost 2 years old, like an airplane. Or he and Gwen, who was 8, would team up to chase their corgi, Marshmallow, around the house. But Webber had recently quit his job as legal director for a software company, and he was feeling restless and out of sorts. Nothing seemed to make sense. Then, one night in May of last year, after the girls had gone to bed, he sat down in the living room next to DeeDee, who was folding laundry.

“I have to tell you about something,” he told her. “An idea I have. But don’t be mad.”

Oh, God, she thought. Something about his manner made her uneasy.

“I think I need to go to Ukraine,” he said. “I want to go help.”

He’d been looking into opportunities to volunteer, and he thought he could use his experience in Afghanistan to teach Ukraine’s medics how to treat combat wounds. “I can train these people to save themselves,” he told DeeDee.

She was stunned. She had no idea he’d been considering something so rash. It seemed like a terrible idea. She wanted to talk him out of it, wanted to persuade him to stay. But she could see his mind was made up. So instead, she gave him a direct order.

“You’re not going near the front lines,” she demanded. “You’re not going to do that. You’re going to be far from the front.” She made him promise.

“Yeah,” he replied. He’d be working for a nongovernmental organization, he assured her. It wouldn’t be long. He’d only be gone for eight weeks.

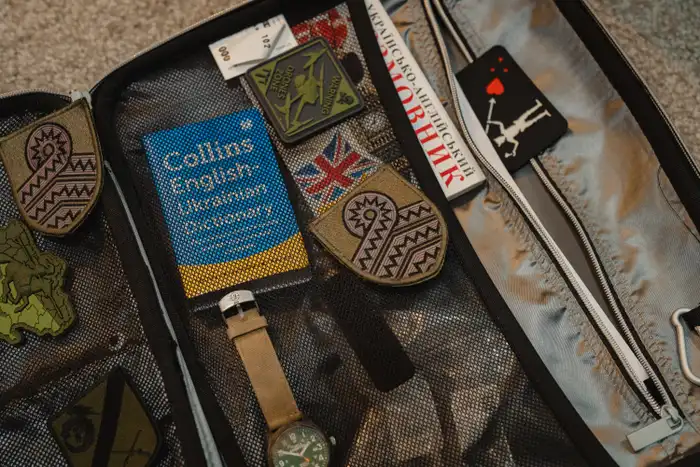

Webber went to Ukraine with insignia he earned in the Army and “Memoirs of an Infantry Officer,” a classic novel from the First World War.

On June 1, less than two weeks later, she was driving him to the airport and helping him check his bags — the Army backpack she’d stenciled with a Red Cross symbol years ago, a large black duffel, parts of a suitcase set she’d bought for Christmas. She kissed him goodbye in the security line, then turned to wave to him one last time. He was wearing a black White Sox T-shirt with an image of an eagle, its wings spread wide. It made him look unusually patriotic. Then she walked back to the car and sobbed.

Now, as Webber and his fellow members of Chosen Company got acquainted in the bar, uncertainty hung over the gathering. The war had been raging for about 16 months, consuming men and matériel at a level not seen on the European continent since World War II. One of the men, a bearded medic who went by the call sign Tango, had been in Bakhmut during the hellish battle for the city, known as “the meat grinder.” Going over to the bar’s karaoke machine, he selected “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen, and some of the volunteers began to sing along.

If I’m not back again this time tomorrow

Carry on, carry on as if nothing really matters

Webber’s voice rose along with those of his new comrades. He hadn’t told his wife, but he was about to break his promise.

Born in 1983, Webber grew up in a small town in a coastal region of Washington state known for its old farms and logging operations. He was raised in a turn-of-the-century house and played in the fields near the family’s barn with his three younger sisters. The kids would put on their grandfather’s helmets and jackets from World War II, stuff pillows down their shirts, and break up into teams to play war with horse chestnuts. Andrew’s favorite part was figuring out strategy on the fly as the projectiles zipped past his head.

In high school, Webber was scrawny but strong, with a broken nose from wrestling. He wore a smirk that people either loved or hated, and he made friends easily. “Being a part of his world, you really feel like you’re in this spotlight,” says his sister Nichole. “And you’re also not going to talk him out of anything.”

Webber entered the Army through West Point. As a cadet, he earned a reputation as a tough but easygoing guy with a romantic streak. “Always up for a random adventure or lost cause,” he wrote in his yearbook entry. He was hooah for the grind of Army life, the shooting and rucking and sleeping outdoors, and he was obsessed with military history. In conversation he’d often reference some obscure battle, and he sometimes spoke about the American soldiers of fortune who had volunteered for the French Foreign Legion or fought in the Rhodesian Bush War, men on history’s margins who made a career out of conflict.

Webber and Dee Dee met when he was a cadet at West Point. “Always up for a random adventure or lost cause,” he wrote in his yearbook.

Determined to distinguish himself, Webber enrolled in Ranger School. The training was grueling: marching 10 miles a day with 100 pounds on his back, then sleeping two or three hours a night before doing it all again. One night, after completing a patrol through the mountains of Georgia, Webber and his fellow Ranger candidates made camp long past midnight. Even in the faint glow of their flashlights, Webber looked filthy, grime caked over his face paint. Everyone was beyond exhausted, but Webber was wearing that smirk that showed he was “just loving it too much,” recalls his friend David Roller. “He would go do the hardest thing he could do, and maybe not even have a rationale for it. It’s just like: Well, I’m going to go do this so no one can talk shit to me.”

After a 15-month tour in Iraq, Webber deployed to Afghanistan in 2008. The war was in its eighth year and going sideways. By that point, many American officers were just going through the motions. Not Webber. As a 25-year-old captain, he sensed he was part of history. He learned Dari and Pashto and made a point of chatting up villagers and farmers to gather intel. At Forward Operating Base Sweeney, in Afghanistan’s borderlands, he would hang out with Afghan soldiers for hours on end and teach them to read the Quran. They called him “the wrestler.”

One day, while accompanying a convoy of Afghan troops who had dropped medical supplies at a remote firebase, Webber was manning the gun mount atop the lead Humvee when it struck a bomb planted on the dirt road. Given his position, Webber bore the brunt of the blast. The vehicle burst into flames, and the Taliban opened fire.

Tom Mader, an Army physician who had been riding in the Humvee, was hit in the leg, knocking him down. As he crawled frantically to get out of the open, Webber climbed back on top of the blasted Humvee and opened fire with its mounted grenade launcher. The Taliban fled, enabling Webber and his fellow soldiers to get Mader onto a stretcher and carry him up a hill to a waiting helicopter, which airlifted him to a hospital.

“I owe him a lot, having jumped up on top of the vehicle like that,” Mader says. “He didn’t have to do that.”

But back at the outpost, Webber kept repeating himself. He vomited and reported splitting headaches. He was flown to Kandahar, where he was diagnosed with a mild TBI, or traumatic brain injury. After a week of treatment, he returned to duty.

But even after his yearlong deployment, the blast’s effects lingered. Back in Georgia, Webber suffered debilitating migraines. One day, while driving to his job as an infantry training officer at Fort Benning, his mind went blank. “I was like, where am I?” he told his mom afterward. He started taking notes with him to work, to remind himself of where he was going and what he needed to do. Sometimes he’d be in a meeting, or leaving his house, and he would suddenly start patting himself all over. Left shoulder, right shoulder, left hip, right hip. Sealed pocket, pistol, rifle mags, first aid. Check. It was the weapons scan performed right before a mission.

“He had no clue that he did it,” recalls DeeDee, who asked him about it. “It wasn’t harming me, so I never brought it up again. It was just one of those Andrew things.”

Webber on a convoy in Afghanistan in 2009. Unlike most officers, he made a point of learning Dari and Pashto, enabling him to chat up villagers and farmers to gather intel.

When Webber departed for Ukraine last summer, he wasn’t exactly in fighting shape. He was 20 or so pounds overweight. It had been 10 years since he was last in combat, and he wasn’t interested in returning to battle. Just before he left Seattle, he told an Army friend that “the key will be finding a way to help without being grinder meat.” He believed that launching “frontal assault attacks” against the Russian army was “kind of pointless.”

“I don’t think I’ll ultimately be doing the trench warfare stuff,” he texted his friend.

After arriving in Ukraine, he was shocked by what he saw. The troops were often kids fresh out of school or guys in their 60s who were as old as his dad. They were sent into the field without enough guns, ammo, or artillery support. It felt, he told his mom, Karla Stephens-Webber, like “sending people to get mowed down in the Civil War.”

Karla knew her son. As she read his texts, her first thought was: He’s going to jump into this.

David Roller, Webber’s Ranger buddy, had tried to talk him out of going to Ukraine. “This is a young man’s game,” he told his friend. “You don’t have to engage in this fight. There’s a lot of things you can do outside of pulling triggers.” But it wasn’t long before Webber was sharing photos and videos with friends back home of combat maneuvers and training exercises. One showed an assault team clearing a World War I-style bunker, using live rounds.

“Andrew, what are you doing man?” Roller texted.

Webber responded with the news: He was readying for a combat mission.

Holy shit, Roller thought to himself. He’s pulling triggers right now.

Chosen Company, one of the best-known units among the international troops fighting in Ukraine, was part of the army’s 59th Separate Motorized Infantry Brigade. It was supposed to be a reconnaissance unit, not an assault force. But on July 4, 2023, the company was given a green light from the Ukrainian military to launch an assault on a village called Pervomaiske. For the fourth time in his life, Webber was going to war.

There wasn’t much left of the place. Shelling had reduced the buildings to rubble. Vehicles sat abandoned among the blackberry bushes and shattered trees, a wasteland of busted concrete and twisted rebar that was littered with land mines and unexploded ordnance. The mission was to clear the village, seize a dilapidated house with a pool out back that Chosen called Objective Kyiv, and begin to open a path for an assault on Donetsk, a major industrial city occupied by the Russians.

It was during that first push into Pervomaiske that the men of Chosen saw how Webber handled himself in battle. Dubs, as they called him, was a leader and a “wizard” with an M320 single-shot grenade launcher — the best some of them had ever seen. He could “put the grenade anywhere he wanted,” one marveled. Another recalled that Webber could put one of the high-explosive rounds through a window at 200 yards.

Chosen snatched a battlefield win from the Russians with relative ease, despite some clumsy missteps and unforced errors. They regained control of half the village, providing Ukrainian troops with access to positions they hadn’t held since the war began. The unit reported only one injury, while the invading forces suffered numerous killed and wounded. One Chosen volunteer called it his “chillest day of war.”

But Webber, with his combat experience, knew how quickly fortunes can change on the battlefield. “When our team steps off,” he texted B-17 after the assault on Pervomaiske, “it is mission accomplishment or death, no exceptions.”

Yet Webber rushed in anyway. Even though the battle had given him a clearer picture of the inexperience within Chosen, he told friends he was going to stick it out. He had a soft spot for green troops, and he thought he could whip the newbies into shape. His fellow soldiers say he was always the first to raise his hand, the first to volunteer for missions. “If I would’ve told him to stay out of the field, he would’ve told me to fuck myself,” says Ryan O’Leary, Chosen Company’s commander. “It’s just how he was. He was going to go where he was needed. All he wanted to do was contribute.”

Webber on the battlefield in Pervomaiske. His fellow soldiers counted on his leadership. “He was going to go where he was needed,” his commander says. “All he wanted to do was contribute.”

On LinkedIn, Webber labeled his service in Ukraine an “internship.” It wasn’t. He had journeyed to Ukraine at a crossroads in his legal career. Now, back on the battlefield, he recoiled at the thought of returning to his law firm.

“I can’t go back to my job,” he texted DeeDee. “Are you OK with that?”

“Yes, yes, yes,” she replied.

Law practice, he had found, wasn’t what it was cracked up to be. After graduating from law school at Northwestern, where he became an avid White Sox fan, Webber went to work for Fenwick & West, a leading law firm in the technology sector. “Andrew was one of those kind, calm souls who took things in stride,” recalls Elizabeth Gil, who worked with Webber at Fenwick. “He didn’t carry that aura of frenzied busyness that’s typical of associates.”

But behind the calm facade, the work was taking a toll on Webber. He was on track to earn over $400,000 a year, but the stress was starting to get to him. He met with a financial advisor. How could he leave Big Law, he wanted to know, and still support his family?

Then, while Webber was on paternity leave from his job, Afghanistan fell. It was August 2021. Dire scenes flooded the news. Masses of desperate people pressed against the gates at the airport in Kabul; crowds chased after departing aircraft. Afghans clung to a C-17 cargo plane while it was taking off, with some falling to their deaths.

His phone was soon overflowing with texts — some from Afghans he’d worked alongside almost a decade ago, many from people he didn’t even know. Soldiers, interpreters, civil servants — they all pleaded with him to help them flee the country before they could be killed by the Taliban for having supported the American invasion.

Webber helped hundreds of Afghans apply for asylum in America.

In typical fashion, Webber snapped into action. Working the phones and the computer day and night, he’d take information from the Afghans and connect them to a team at Fenwick, who would help them fill out US immigration forms that could run up to 200 pages. Sometimes, in Zoom meetings with his team, Webber would have his newborn, Vera, on his lap. He’d scrunch her hair into a mohawk to make his colleagues laugh.

He did the work pro bono. He didn’t view it as a charitable cause he should be billing hours toward. It was a responsibility. His responsibility. As an Army officer, he had given his word to these people. We’re going to take care of you. We won’t abandon you. Now he was making good on his promise.

But as the months dragged on and the calls kept coming, Webber began to feel crushed by the weight of what he had taken on. The United States had evacuated more than 75,000 Afghans, but hundreds of thousands had been left behind, more than Webber and his small team could ever hope to process, let alone get to safety. He and his team had helped hundreds of Afghans apply for asylum. But it came to a point where he couldn’t do more. He deleted WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger from his phone. It was over.

“He would’ve been doing it 24 hours a day if he could,” says Hilarie Atkisson, a colleague at Fenwick. “I think it haunted him.”

Those he managed to help were grateful that one American, at least, had kept his word. “He’s so kind and so different than other commanders,” says Asmat, an Afghan translator who’s awaiting word on a visa that Webber helped him apply for. “When he promised something, he would do it. Some other commanders, it was just talking.”

Back at Fenwick, Webber grew even more restless. His work with Afghan refugees seemed to have awakened something in him. He got a job as the top in-house counsel at an information-technology company, but he found it tedious to work on stuff like restricted stock unit grants and multitiered warrant structures. He left after a year.

It was early 2023, and the war in Ukraine was once again in the news. Ukrainian troops had managed to stop the Russian war machine in its tracks, and a big counteroffensive loomed. To Webber, it felt like the moment to jump in and help.

“A lot of people who end up in Ukraine are running away from their past,” says Thomas Waszak, a Ranger veteran who met Webber at a military surplus store in Washington where they had both gone to kit up for Ukraine. “Some go there with a death wish. Some are adrenaline junkies, thrill seekers, and war tourists. Andrew was none of that.”

For Webber, going to Ukraine “wasn’t a decision that was made lightly,” Waszak adds. “I know he loved his wife, and I know he loved his two girls.” But Webber thought the sacrifice was necessary. “He was the epitome of: If good men stand by and do nothing and if not me, who?”

The men of Chosen who fought alongside Webber came to the same conclusion. “He was fighting there on moral reasons,” one says. “He saw it as the right thing to do.” Webber believed in standing up to Russia and fighting for a free Ukraine. “Justice is more than just a word,” he would often tell his brothers in arms. “He wanted to try to help,” another volunteer says. “He thought his skills could be better used in Ukraine than back home in the States.”

In Ukraine, Webber was surprised so few Americans had joined the cause. To him, this seemed like the war that kids who grew up on “G.I. Joe” cartoons and action films like “Red Dawn” were born to fight. “It surprises me that there isn’t like, fucktons of US mil/West Point people here,” Webber texted a friend. “It’s a free war with a fairly clear bad guy.”

He reached out to other vets he knew, urging them to come to Ukraine. “I’m looking for people who want to make a direct contribution to Ukraine’s efforts in their war,” he wrote. “The contribution would put you straight into the razor, bleeding edge of modern warfare.” Volunteers, he added, would receive $3,000 a month in pay from the Ukrainian military, plus all the borscht they could eat. “Come help win a fight and make humanity better off,” he urged. “And if you live, probably become a SME” — subject-matter expert — “in a field with unlimited future demand.”

Grand ideals aside, Chosen Company’s living quarters certainly weren’t a selling point. The building where Webber and his fellow soldiers were housed looked like a bankrupt youth hostel, with filthy floors and fraying furniture. Rooms were littered with the detritus of previous occupants — discarded envelopes, cigarette butts, a tiny Ukrainian flag with trudge marks on it. Stacked ammo boxes served as countertops. One washroom had three sinks. One was out of order; another had a sign that read “sink for dishes.”

The soldiers took their meals on benches at long, wooden tables covered in cheap blue plastic, making them easier to wipe down. The food was blah: porridge and borscht, with a hot dog on top. Webber disliked potatoes, but he often had little choice but to eat them.

Webber urged other American veterans to join him in Ukraine. “Come help win a fight and make humanity better off,” he wrote.

At one point a bandura player came to play for them. It reminded Webber of USO tours to cheer American troops. The musician set up a chair, a mic, and an amp before a waist-high stack of sandbags and a camouflaged curtain. “He said, ‘Two things we must provide our children: our weapons and our culture,'” Webber texted a friend back home. “That was kind of deep. And tragic.”

Webber was different from many of the vets drawn to Chosen. O’Leary, the unit’s commander, says it attracted a lot of “let’s go fuck shit up” types who could be secretive and paranoid. Earlier this year, a German medic who served in Chosen accused the unit of killing unarmed Russian soldiers who were trying to surrender. No charges have been filed, and the killings were said to have taken place long after Webber served in the unit. But the accusations underscore the gung-ho, take-no-prisoners attitude that was typical of many of the volunteers who signed up with Chosen. Webber wasn’t like that, the medic says. “He was genuinely a good person.”

Webber was quieter, less in your face, more analytical. He was also compassionate and kind, his humanity surprisingly intact despite years of war. His fellow soldiers marveled at the things he’d do, like rushing into a building under enemy fire to rescue a kitten. Many saw him as something of a big brother. “He did a good job of managing a lot of the younger guys that hadn’t been in a fight before,” Tango recalls. “Just kind of making sure they’re not wasting ammo, they’re not freaking out, and nobody’s flipping out or freezing up.” Even the more jaded vets valued what Webber had to offer. “We didn’t spend a lot of time skipping through fucking rainbows and shit together,” another soldier says. “I imagine what we did was ugly work, and it was fucking ugly. But you know what? I was fucking thankful I had him next to me every goddamn time.”

Now, a few weeks after the assault that had liberated half of Pervomaiske, Chosen Company had new marching orders. They were going back to finish the job.

It was going to be the same drill as before. Working off the latest battlefield intelligence, they planned to hit the village in the same spot, in the same way. The key to success was speed and surprise. “We’re a lightning assault unit,” boasts one member of Chosen Company. “Storming trenches is what we do.”

Before the assault, there was a nervous energy among the men. Some sat quietly or cracked jokes. Others sang crude renditions of the internet sensation “Dumb Ways to Die.” As for Webber, he had an uneasy feeling about the operation. Before Chosen moved out, he approached Wayne Hallatt, a Canadian volunteer with a bushy beard who went by the call sign DirtyP, for a word in private. “Hey, man, make sure you’re ready to run up and lead the section,” Webber told Hallatt.

“Nah, man, you’re leading the section,” Hallatt replied. “I’m not taking that from you.”

But Webber was insistent, “I think this is going to go bad,” he said. “Like I have a bad feeling about this one. If something goes bad, I need you to come up and take over.”

Cats are everywhere on the front lines in Ukraine; Webber rescued one from a building under fire.

As Hallatt later recounted on Funker530, a video platform for veterans, it made him uneasy to hear Dubs putting that kind of “bad juju” out into the universe. He tried reassuring his friend. “Everyone’s going to be fine,” he said. “You’re a fucking solid leader. You got this. You’re going to make sure the boys are good. You’re going to be good. You’re all coming back.”

He had no idea what Chosen was about to run into.

Chosen Company launched its second assault on Pervomaiske on July 29, 2023. The sun was sitting lower in the sky as dusk approached, casting long shadows on the twisted wreckage. But minutes after the soldiers stepped off, tramping through abandoned fields flecked with yellow daisies, it became clear that this wouldn’t be anything like the last mission. Chosen hadn’t caught the enemy off guard. The Russians were waiting for them, and the assault quickly turned into what O’Leary called “a shitstorm.”

There were mines everywhere, “dropper drones” that released grenades over the battlefield, and exploding drones that screamed as they dive-bombed into their targets. In the weeks since the first assault, Russia had reinforced its positions with more capable troops who were hammering Chosen with highly accurate mortar and machine-gun fire. “They knew what they were doing,” recalls Tango, a company medic. “They brought in all their big hitters to play, and then they set up basically a kilometer-long complex ambush waiting for us.”

Tango, Delta Team’s medic, treats a wounded soldier on the battlefield Pervomaiske.

Wearing his combat fatigues, helmet, and body armor, which were marked with yellow identifying tape, Dubs was right where he had promised his wife he wouldn’t be. He was calling the shots for Delta team while returning fire with his folding-stock AK and the M320 that he carried down on his hip. A bandolier of 40 mm grenades ran across his chest, and on his left shoulder, he wore the wing and bayonet patch of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, one of the Army’s most storied units, with whom he had been a troop commander during his final tour in Afghanistan.

“He honestly was somebody that had real experience leading soldiers,” one volunteer recalls. “So that put him at the top of the list as far as qualifications and experience go for leaders of combat teams. Quite frankly, to put anybody else in charge would’ve been somewhat negligent.”

Delta was one of four Chosen assault teams pushing in parallel toward their main objective: a Russian-held bridge on the route to Donetsk. The terrain was rough but flat, leaving no options for sniper overwatch. To make matters worse, Webber had lost the radio he needed to communicate with Chosen Company’s command and call for support, and their backup unit wasn’t working. Without a radio, Delta’s lifeline had been severed.

The other teams were pinned down, and Delta was advancing alone. They moved from rubble pile to rubble pile. Every step was dicey; all around them were trip wires, anti-personnel mines, and stacks of anti-tank mines that could be set off by a stray bullet or a grenade blast. In the midst of the chaos, one soldier recalls, Webber remained “cool, like a cucumber.” But Delta had no answer for the increasingly overwhelming Russian fire they faced. The team couldn’t move forward, nor could they hold where they were. They had started taking casualties, and they had no idea how the other teams were holding up. Webber gave the order to fall back. The assault had failed.

Webber’s decision saved lives. If Delta had stayed out on the forward edge for much longer, the whole team might have been wiped out. But getting back was not as simple as turning around and walking off the field. The team began fighting its way back through the overgrowth and rubble, assaulted by drones and shelled by mortars. They tried taking cover by a roofless house, its white walls perforated like a pegboard, but immediately realized there was nowhere to hide. They kept moving. There were Russian bunkers concealed throughout the area, but sometimes the food wrappers, purple bags of feces, and bottles of urine scattered nearby gave them away. As the team withdrew, they set one of the bunkers on fire.

As Delta dropped back, Webber and another American, Lance Lawrence, helped lay down suppressive fire to cover the withdrawal. The two men, along with several others, were holding up the rear as others on the team tried to help CeeBee, an injured soldier, off the field. Suddenly, Delta was hit by a barrage of grenades and air-burst mortar fire. “That knocked down pretty much everybody,” recalls Tango. In an instant, the field was littered with wounded soldiers.

Lawrence was lying face down, struggling to get back up. CeeBee was bleeding out. Tango had been shredded by shrapnel; one leg was paralyzed from the knee down. Another man was missing several fingers.

And then there was Webber.

Before the operation, a member of Chosen had asked Dubs what he was going to do if he got injured. “Well,” Webber responded, “it’ll be fine until it’s not. And when it’s not, you just deal with it.”

It was no longer fine.

The shrapnel from the mortar fire had cut deep. “He got hit really bad,” recalls Tango. “It tore right through his guts and hit him in the side.” Despite his own injuries, Tango raced to tend to Webber. “I started stripping Dubs, checking him, making sure everything was good. It was definitely not good. He had a massive hole in his side from a piece of mortar.” After he stabilized Webber, he moved on to the next man.

Tango got to Lawrence and bandaged him up, the battle still raging around them. But by the time he was able to circle back again, Lawrence was on his last breath. Tango sat with him until the end.

Still able to hold a rifle with his one good hand, Tango defended his wounded team while trying to keep pressure on Webber’s wound. The shrapnel had damaged his lungs, and he was having trouble breathing. They sat there in the overgrown, blood-stained field for an hour, waiting for help to arrive and praying a drone didn’t spot them. But there came a point when Webber couldn’t hold on any longer. The internal damage from the mortar shell had been catastrophic. He asked Tango to tell his family that he loved them and to make sure that the other guys got out safe. Then he was gone.

“He was worried about everyone else up to the end,” Tango recalls.

The rest of Chosen had also suffered heavy casualties. “Russia threw basically fucking everything at us but a fucking ballistic missile that day,” O’Leary recalls. Only under the cover of darkness were volunteers able to retrieve Webber’s and Lawrence’s bodies. As the rescue team sped off in a Humvee, it narrowly missed being struck by a Russian shell.

“We were inseparable,” DeeDee says. “Best friends that just happened to be married to each other.”

The night before he died, Webber called DeeDee. When he rang, she was at the chemistry lab where she worked. “Hey, we’re going out,” he told her. “I’m going to be off-grid for a couple of days.”

DeeDee had years of experience as an Army wife. She knew what it was like to live with anxiety for months on end while she waited for Andrew to come home. But this wasn’t like his other tours of duty. Two months earlier, when he had first talked to her about going to Ukraine, he had promised to stay out of combat. DeeDee didn’t know that he had joined an assault company. She didn’t even know where he was, or who he was with. When they spoke, everything was shrouded in a secrecy that felt almost paranoid to her. Andrew had been planning to come home in a few weeks. But now, something about his tone didn’t feel right.

“I just have a really bad feeling about this,” she told him. “Please don’t go.”

“It’ll be fine,” he replied.

In his final messages to B-17, just a few days before the mission, Webber was more honest about what he was facing. “We’re literally running into Russian fortifications and killing people at like, 5 meters away,” he texted a few days before the assault. In combat, he observed, “stay safe” isn’t really an option. It’s more like “don’t die cheap.”

Chosen Company never took Pervomaiske. Following a memorial service for Webber in the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv, his friend Waszak brought his ashes home to his family. A year after his death, they’re finding ways to carry on his legacy. His mother, Karla, met with congressional representatives to support the passage of a Ukraine aid deal that blunted Russia’s momentum. His sister Nichole says she’s trying to live up to his high standards, which have “always made me be a better person.” And DeeDee is beginning to feel more grounded after moving closer to her own family. She and the girls still have trouble sleeping, but she’s learning to “settle in” with her grief. “I feel he’s always with me and the girls,” she says, “so that gives me some peace.”

Webber’s family is still grappling with their grief. “I feel he’s always with me and the girls,” DeeDee says. “So that gives me some peace.”

Those who fought alongside Webber in Ukraine are still trying to make sense of why he was there — and what inspires so many of them to remain. “It seemed like he had stuff he was working on,” says O’Leary, the CO of Chosen Company. “I think a lot of veterans of the global war on terror are that way. It was like, my contribution and my sacrifice and my friends’ lives who died in Iraq or Afghanistan — what did it mean? A lot of vets think that all the time.”

Tango, the medic who fought to save Webber, says that many veterans who served in the Middle East see Ukraine as an opportunity for “redemption” — a just war to balance against America’s failures in Iraq and Afghanistan. “We went and fought for a war, but what was it really worth?” he says. “And then we wanted to come here and fight for something that actually truly mattered, that was totally right. I think that was a big motivation for a lot of guys, especially US vets who have come here.”

Another member of Chosen summed up the feeling. “For all of us that were in Afghanistan,” he says, “Ukraine was a big calling for us to have a second try and sort of see it to the end.”