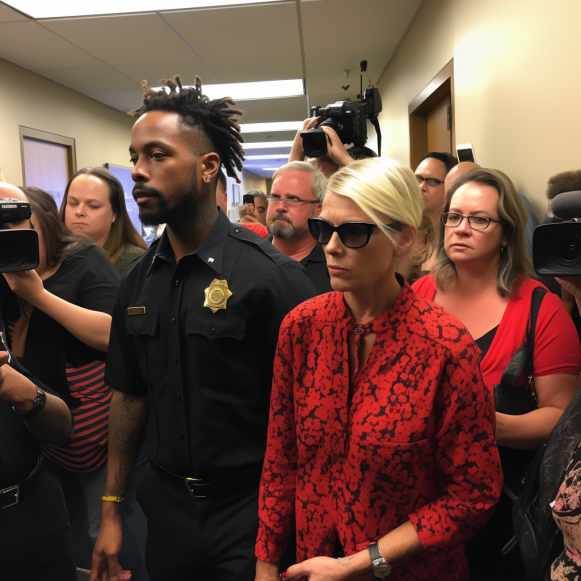

New documents raise questions about hiring of Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price’s boyfriend

The job that Antwon Cloird received was not publicly advertised, county officials say

OAKLAND, Calif. — According to newly obtained records, Alameda District Attorney Pamela Price’s boyfriend was hired for a position within her office that was never publicly advertised, despite potential red flags about his tenure at a company that he then claimed to help run.

Antwon Cloird, Price’s romantic partner, oversaw a Richmond-based company that ran afoul of state tax officials, according to records. What that company does is unknown to the person listed as its business agent, who claims to have never heard of it.

The new information about Cloird’s prior work history, as well as the apparent lack of competition he faced in landing a job with Price’s office, raises new concerns about the circumstances of his employment, which was first reported by this news organization last month. Ethics experts who have criticized his new job now believe Price and the county did not follow good governance standards when hiring Cloird.

It “just doesn’t pass the ethical test,” according to John Pelissero, a senior scholar in government ethics at Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. “The DA and the DA’s Office should be concerned about appearances. This does not appear to be a good situation.”

A transparent hiring process is essential in government affairs because it “avoids any sort of favoritism, discrimination, and embraces equal opportunity,” according to Michael Martello, a former city attorney for Mountain View and Concord.

“The best practice — and the fairest — for a public sector position is one that is well advertised, open to everyone, and has a very predictable process,” Martello said.

According to Cloird’s résumé and job application, he spent the previous five years as the chief operations officer of Community Partnership Alliance, LLC, the company whose operations were halted by state tax officials.

Nonetheless, Cloird was able to land a job as a “senior program specialist” with a salary of $115,502. According to records, he is paid $10,500 more per year than another new hire in his same unit, despite having a background in social work and a master’s degree. Cloird did not have a four-year college degree, which was required for the position he held, but the county allows applicants to substitute real-world experience for education.

The District Attorney’s Office declined to comment for this story. Cloird did not respond to an emailed questionnaire.

County officials fought this news organization’s requests to see Cloird’s résumé and job application for months. Only after Cloird personally authorized the disclosure did County Counsel Donna Ziegler release the documents.

In response to questions, Ziegler stated that the county did not advertise the job, but that Price was under no obligation to do so. It is unclear if any other candidates were considered in addition to Cloird.

Cloird, 60, almost immediately went to work on Price’s resentencing and re-entry team, a group whose job it is to identify strong candidates for early release and assess their readiness to rejoin society. According to one former prosecutor, Cloird has approached his job in an unconventional manner, sending lists of people he wants released from prison.

Cloird, a long-time Richmond resident, has both personal and professional experience in the field of re-entry. He was once known as “29 Seconds,” a nickname he still uses to refer to his days on the streets, when he could “get you whatever you needed in 29 seconds.”

Cloird worked as a construction worker for Laborers Union 324 for four years in the late 2000s. According to his résumé, he then founded a nonprofit called Men and Women of Purpose in 2011 and met Price while there, who records show also did legal work for the nonprofit.

He left in 2017 to join Community Partnership Alliance. He worked 40 hours per week, supervising 12 people and performing “program planning, technical assistance, review, and evaluation functions to direct client service delivery programs,” according to his résumé.

“I am the company liaison with service providers and funding sources, and ensure that program regulations and procedures are followed; and to do related work as required,” according to his résumé, which provided few details about the work he did.

State business filings raise a slew of questions about the company’s legal standing.

According to records, the business was suspended nearly two months before Cloird’s arrival by the California Secretary of State’s Office, though the reason for the suspension was not specified. In June 2018, the California Franchise Tax Board followed suit, suspending the company due to an unfiled tax return.

According to the state tax board, the company has been unable to legally operate for more than five years because a $250 balance remained unpaid as of early September.

Furthermore, Phil Allen, the attorney whose name appears as the company’s registered agent on filings with the California Secretary of State’s Office, stated that he had never heard of the company or Bryan Hancock, the man listed as its organizer and signatory. Hancock, a frequent Cloird business partner who also served as a consultant on Price’s 2022 campaign, declined to comment.

Allen claimed that his name was added to the document without his knowledge, but he has previously worked with Cloird.

“The truth is, I’m not sure how I got on this one,” Allen confessed. “I’m not familiar with the name Bryan Hancock.”

While business suspensions are common among small California businesses such as Community Partnership Alliance, employment and corporate law experts say it is a sign of poor management. And, according to Andrew Verstein, a UCLA law professor and co-director of the Lowell Milken Institute for Business Law and Policy, putting someone’s name down as an agent without their knowledge could be considered perjury.

“This implies either extreme sloppiness, extreme cheapness, extreme ignorance, or some other extreme reason why no registered agent could work with you,” Verstein explained. “They are all bad, but they are all different kinds of bad.”

There isn’t much else known about the Richmond company. On Friday, a woman who answered the phone for the company said its leaders were in meetings and unavailable to speak.

According to its website’s mission statement, it aims “to provide employment opportunities by connecting small businesses, mentoring, and coaching along the way.” It makes no mention of such companies, but it does mention Cloird and his goal of “equality for individuals willing and ready for a second chance at a first-class life.”

According to the congregation’s minister, Pastor Donnie Featherstone, its address can be traced back to a Richmond storefront on Macdonald Avenue that housed a church for the last seven or eight years. He claimed he had never heard of Community Partnership Alliance but knew Cloird from his childhood, had seen him working in the building and referred to him as a “workaholic” and “a go-getter.”

Previous reporting by this news organization revealed deep concerns from government ethics experts about Price’s hiring of her boyfriend, citing the corrosive nature of nepotism and the blow to public trust that such hires cause. It also discovered that Cloird drew the FBI’s attention in 2015 amid allegations that he extorted Richmond business owners for tens of thousands of dollars, despite the fact that no criminal charges were ever filed.

Alameda County has no anti-nepotism policy, which has been criticized in multiple county civil grand jury reports over the last decade, so Price was under no obligation to notify anyone about Cloird’s hiring, and she did not do so voluntarily, county human resources officials previously stated.

Price has since defended Cloird’s presence on her staff by citing the county’s lack of nepotism policies.

She has also called criticism of the hire a “double standard,” citing the fact that her predecessor, Nancy O’Malley, hired several relatives, including her sister and nephew.

“There are probably some other O’Malleys there that I don’t know about,” Price said at a Wellstone Democratic Renewal Club town hall in late August.

In an interview, LaDoris Cordell, a retired Santa Clara County judge and former San Jose Independent Police Auditor, called the DA’s stance “hypocritical.” She simply stated, “You can’t have it both ways.”

“You can’t say, ‘I’m going to be progressive and transparent, and this is a new day,’ and then act like the person who ran the office before you, who you’ve criticized,” Cordell said. “And that’s exactly what happened here. Everyone understands that nepotism is wrong, so the county should have an anti-nepotism policy.”

“They should be correcting this,” Cordell added. “Where is the integrity?”