A lawsuit accuses Bain Capital’s PowerSchool of trafficking in student data. The edtech giant says everything it does is legal.

PowerSchool manages data for 60 million students and their educators.

It’s been 10 years since Emily Cherkin helped her son log onto a school computer on his first day of Kindergarten.

“He can’t even write his name. Why am I teaching a five-year-old control-alt-delete?” she remembers asking herself.

Cherkin, a Seattle mother of two, former teacher, and author of the new parenting guide “The Screentime Solution,” is now the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit that alleges the education technology giant PowerSchool is selling student data, including health and disciplinary records, to its third-party “partners,” and doing so without the informed consent of kids or parents.

The lawsuit, filed in May in federal court in San Francisco, takes on the world’s largest provider of cloud-based software for K-12 schools.

PowerSchool, based in Folsom, California, manages data and crunches it into what it calls “analytics and insights” for more than 60 million students and their educators, including at 90 of the top 100 US school systems by enrollment size.

Boston-based private equity firm Bain Capital acquired PowerSchool for $5.6 billion in a deal finalized October 1. PowerSchool CEO Hardeep Gulati said the merger will help the company expand its award-winning products, including PowerBuddy, its new generative AI platform.

With two parents and their children as sole plaintiffs, the Cherkin lawsuit may seem a small effort by comparison, but it’s throwing big rocks.

The lawsuit caps Cherkin’s decade of concern about children and screen time. It calls PowerSchool a “multibillion-dollar surveillance-technology empire.” It demands that the company pay back untold millions of dollars earned by selling student data “products” to more than 100 of its partners, including educational consulting firms and government policymakers.

One partner, an educational consulting firm, offers marketing guidance to colleges, trade schools, and the military based on data from the 6 million high school students who use PowerSchool’s Naviance college-planning software, the lawsuit alleges.

“PowerSchool collects this highly sensitive information under the guise of educational support,” the lawsuit alleges, “but in fact collects it for its own commercial gain,” while hiding behind “opaque terms of service such that no one can understand.”

PowerSchool is throwing big rocks back.

The days of “spiral-bound grading books” are long over, the edtech company’s lawyers counter in a motion to dismiss filed in July.

The motion argues that PowerSchools is legally allowed to collect data voluntarily submitted by students and administrators, along with metadata about “unique device identifiers,” IP addresses, and “cookie data.”

PowerSchool also argues that it “adequately discloses” what data it collects.

PowerSchool spokesman Austin Zerbach told B-17 that no PowerSchool product sells any form of student data.

“PowerSchool does not endorse or support any use of student educational records other than as agreed to by our customers, the schools and districts controlling the student education record, nor do we conduct targeted advertising with personal data of students,” PowerSchool spokesman Zerbach said in a written statement.

A 345-terabyte trove of data

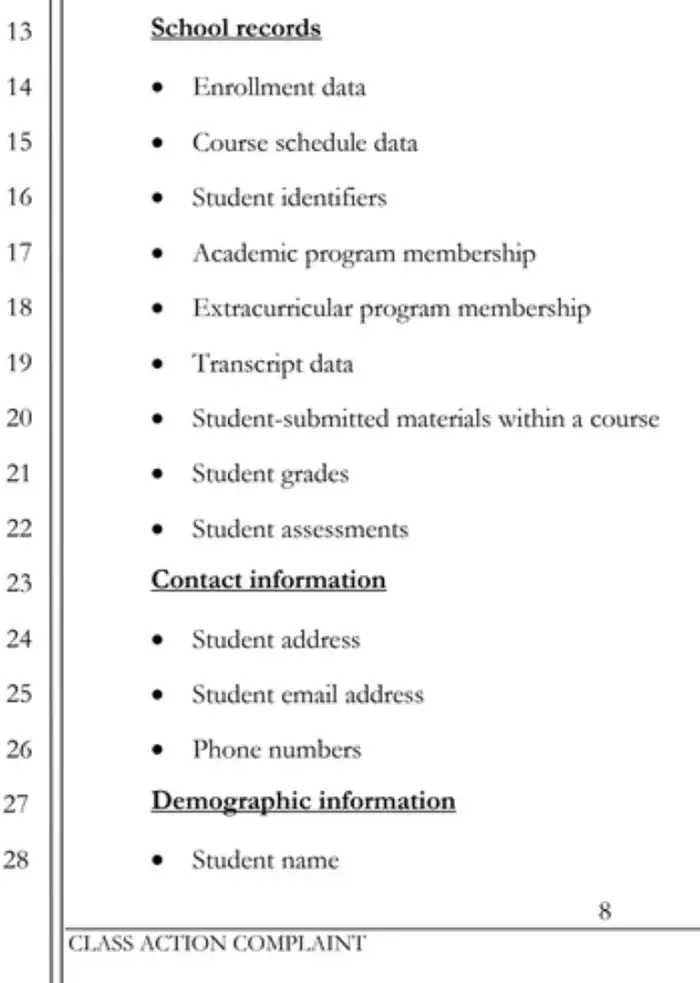

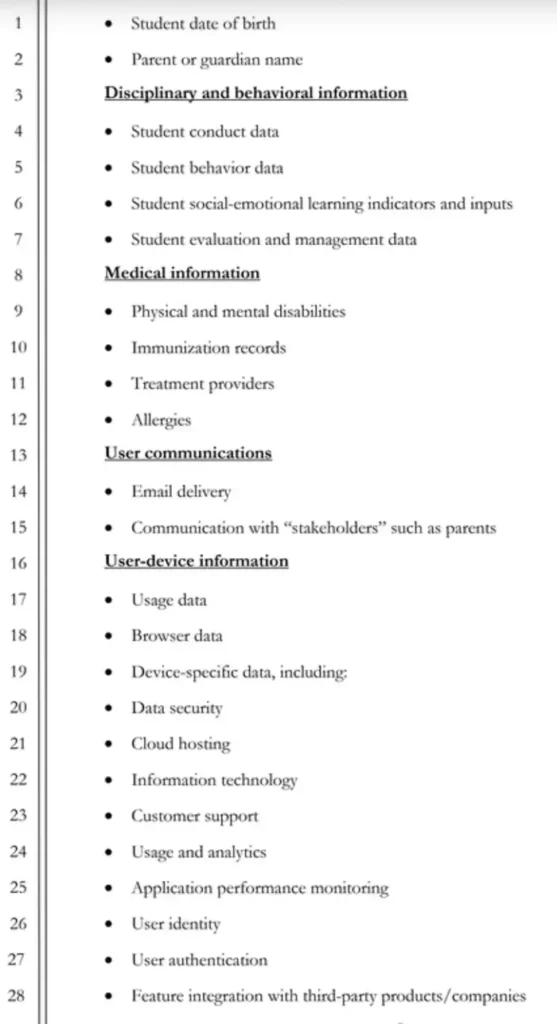

The information PowerSchool collects from students is “virtually unlimited,” the lawsuit says.

It lists more than 50 kinds of data that PowerSchool says in public disclosures it “may” collect, including “extracurricular program membership” and “student assessments.”

The public disclosures of PowerSchool say the edtech company “may” collect data such as “extracurricular program membership” and “student assessments.”

PowerSchool also tells users it may collect “student behavior data” and information about “physical and mental disabilities,” according to the lawsuit.

PowerSchool’s “data trove” totals some “345 terabytes of data collected from 440 school districts,” and includes information from nearly 20 edtech companies it has acquired since 2015, including Schoololgy and Kickboard, a “student behavior management and reporting program,” the lawsuit alleges.

What’s done with the data?

The lawsuit alleges that in addition to being aggregated into lucrative analytics “products” for third parties, it’s used to “train its AI technologies,” including a PowerBuddy chatbot marketed not only to educators but to “state officials” for the purpose of “workforce planning,” the lawsuit alleges.

PowerSchool also publicly discloses that it may collect “student behavior data” and records of “physical and mental disabilities,” the Cherkin lawsuit alleges.

The data is anonymized

The data shared with third parties is anonymized, but the lawsuit raises concerns that it is so “granular” that it can be reverse-engineered to identify individual students.

“There are data brokers — they’re called identity-resolution companies — that collect information from internet users, re-identify the data, and then sell it,” said attorney Julie Liddell, whose Austin, Texas-based EdTech Law Center represents Cherkin in the suit.

Technology can easily re-identify anonymized student data, said Chad Marlow, senior policy counsel at the ACLU, where he focuses on privacy, surveillance, and technology issues.

“A generation ago, the most private student data was kept in a locked steel file cabinet in the principal’s office, and it was very hard to share that information,” Marlow said. “Nowadays the ability to share and reshare that data can be as easy as pressing a key on a keyboard.”

PowerSchool markets student data “analytics” to state government agencies. The systems can “improve student outcomes and create pathways to social mobility.”

Among the “products” PowerSchool offers educators, policymakers, and government agencies is its “P20W Cradle-to-Career State Data Systems.”

Its data is touted as “longitudinal,” captured from the same students from K-12 through post-secondary education and into the workforce.

PowerSchool markets “efficient access to both historical and current data” from students to government agencies.

“It’s telling state and local governments, ‘You will not get a more robust picture of children, starting from their earliest days,'” said Liddell.

“And this is not just for educational services,” she told B-17. “It’s for workforce planning, for healthcare planning, for juvenile justice and law enforcement planning,” she said.

PowerSchool’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, including on grounds that it misapplies the law and fails to state “actual damages,” will be argued in San Francisco on Thursday before US District Judge James Donato.

“The claims made in the complaint are unfounded and inaccurate,” Zerbach, the PowerSchool spokesman, told B-17.

The company “strictly and proactively follows all legal, regulatory, and voluntary requirements for protecting student privacy,” the statement said, pointing to PowerSchool’s online “commitment to protecting student data privacy.”

“No PowerSchool product, including Connected Intelligence P20W, sells any form of student data,” the spokesman said. “Connected Intelligence P20W provides a unified, secure, and integrated platform for education and government agencies to securely unify, integrate, and access their own source system data in a state-specific data cloud. As with all PowerSchool products, only authorized users have data access with stringent data governance as defined by the state agency. “

PowerSchool began selling software to help schools track grades, attendance, and enrollment in 1996.

Apple purchased the company for $62 million in 2001, then sold it to Vista Equity Partners in 2015. Vista Equity retains a minority investment stake, as does Onex Partners, according to PowerSchool’s Bain merger announcement.

When the deal closed on October 1, shares of the edtech leader, which had been trading as PWSC, were delisted from the NYSE.

The Bain-PowerSchool deal comes on the heels of global investment firm KKR & Co. Inc’s $4.8 billion acquisition of the Salt Lake City-based edtech firm Instructure Holdings, Inc., announced in July.

“It’s unsurprising that private equity firms are increasingly interested in acquiring companies that have access to troves of highly valuable data,” Liddell told B-17.

As a private company, “they will no longer be legally bound to make even the minimum disclosures required by a public company,” she said.

A spokesperson for Bain Capital did not respond to a request for comment on this story.