Elon Musk’s ‘gamification’ of government spending taps into our natural competitive instinct

It was perhaps inevitable that Elon Musk — a tech titan and a prolific gamer — would try to turn government spending into a game.

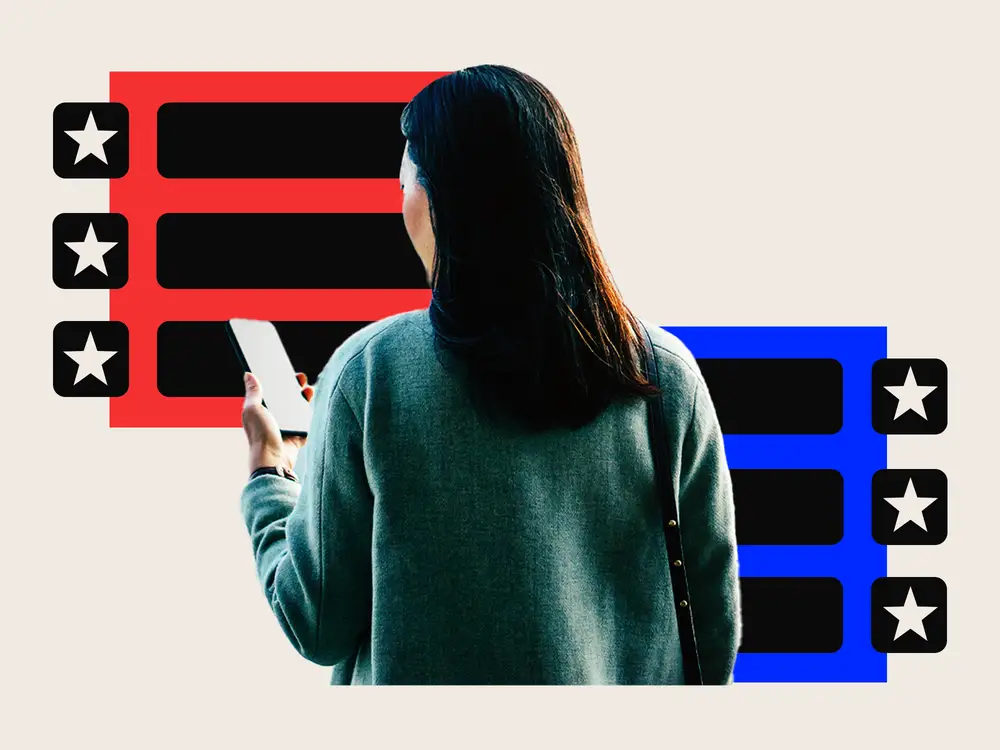

As soon as Musk became co-leader of a newly-minted Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE for short), he proposed a crowd-sourced leaderboard for the dumbest uses of tax dollars.

It’s a natural move for Musk, who came up in the tech world in the early 2000s, as “gamification” took hold. The concept — using gaming features like points and leaderboards to optimize real-world scenarios — was first described by software engineers in 2008.

The gamification movement in business and tech was born from the central idea that “reality is broken,” as futurist Jane McGonigal wrote in her 2011 bestseller. “Game developers know better than anyone else how to inspire extreme effort and reward hard work,” McGonigal wrote.

Fundamentally, these features — real-time updates and comparisons — tap into our natural appetite for control, Adrian Hon, cofounder of the gaming studio Six to Start and author of “You’ve Been Played” on the dark side of gamification, told B-17.

“Most common forms of gamification are based around ideas of reward and punishment. That’s basically behaviorism that’s 100 years old,” Hon said. “It’s very easy to do. It’s very easy to understand.”

These days, gaming features are baked into the fabric of much of modern life, particularly social. Millions of people “like” opinions on X, down-vote news on Reddit, and earn badges on DuoLingo. We chase steps, close rings, and compete with strangers to spin the fastest.

The question is how to add context to make complex goals understandable, exciting, and achievable.

Urging someone with a sprained ankle to hit 10,000 steps a day regardless could do more harm than good. In government, pointing to a simple metric that captures “efficiency” is a tall order — on paper, slashing budgets could look good but bring unintended consequences, according to Richard Landers, a psychology professor at University of Minnesota who specializes in gamification.

“The number one most efficient way to have a firefighting department in a small town is don’t have one, because then they never fail,” he said. “That’s that kind of logic that you end up having if you’re not really cautious about how it’s designed.”

Why comparing scores is hardwired into our psychology

A game undeniably makes tasks more digestible — something Musk has been talking about for years. He argued at SXSW in 2014 that education should be “as close to a video game as possible.” “You do not need to tell your kid to play video games. They will play video games on autopilot all day. So if you can make it interactive and engaging, then you can make education far more compelling and far easier to do,” Musk told the audience.

Throw in other players, and you’ve got a race.

Humans have a natural competitive streak. Going head-to-head with a rival can help boost our focus, enhance our attention, and motivate us to stick to a task, research suggests, but it can also backfire if the pressure gets too intense.

A leaderboard works psychologically by incentivizing behavior with a reward like public recognition, maybe a prize, or a sense of accomplishment at winning a competition.

It’s often used for behaviors people already want to do, but need an extra nudge, according to Landers. Think taking a spin class when you’re tempted to watch Netflix, or walking more so you can get the highest step count in the group chat.

“Good gamification is hypothetically the same way, so that when you achieve well on the Nike app, you’re like, ‘yeah, I really did do something for myself this week. That was great,'” he said.

“There’s no question that it motivates people,” said Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, professor of history at the New School and author of “Fit Nation: The Gains and Pains of America’s Exercise Obsession.”

“You’re in the gym running next to someone on the treadmill, you see them speed up, and you want to speed up. Take that experience and multiply it by however many people you’re ranking.”

Politicians love leaderboards

Leaderboards zero in on a specific, measurable goal, like your step count for fitness.

That’s not so straightforward in politics, but it’s incredibly alluring. “Politicians like them because it makes them feel like they have more knowledge and real-time knowledge than they might get otherwise,” Hon said, referring to rankings of programs like schools, hospitals, and fire departments.

Take healthcare. Increasing productivity in an emergency department is complicated — more complicated than any hospital ranking can communicate. In the real world, that sometimes translates to doctors turning down tricky cases in favor of easy ones to pump up their success metrics, according to Landers.

This is one of the biggest unanswered questions facing gamification — can boiling down complex issues into crunchable numbers miss the point?

Landers said leaderboard systems generally require one precise, agreed-upon goal in order to work. If a metric is oversimplified, it can risk losing sight of the original goal as participants start to value the game for its own sake.

“Empowering individuals to call out true waste is not inherently a bad idea,” Landers said. “The challenge would be in defining that. How do you know when something is legitimately wasteful?”

For the government, that might hinge on what counts as waste and whether Musk’s leaderboard can get people to agree.

“You can’t just call it waste because you’re like, wow, I don’t think Jill over there is a good use of money. You should fire her. It’s not a productive approach. Trying to figure out how to create a system like that would be incredibly complicated,” Landers said. “They would have to do that investment in really understanding the problems deeply and then creating a system to reward what actually should be rewarded.”

Gaming the system can backfire

At the height of Peloton’s popularity, the home fitness brand’s competitive leaderboard quickly became overrun by people hacking their Pelotons to artificially boost their scores.

As a result, some users felt less motivated instead of more.

“The demotivating power of being low on a leaderboard is well understood,” Landers said. “If you’re like 500,000th, nobody cares. You’re like, why even try?”

Petrzela said that even if people play by the rules, overgamifying might mean missing out on valuable but hard-to-quantify things

“If your only goal in Peloton is to be at the top of the leaderboard, you completely sacrifice a lot of the things that might slow you down but make your ride injury-free or something you really enjoy,” she said. “Musk’s proposed leaderboard is a much higher stakes version of that.”

In terms of government services, a goal like reducing wait times for doctors’ visits might translate well to a leaderboard, since they’re easy to compare. But more complicated variables — like whether a cancer program can treat a patient’s specific diagnosis — might fall through the cracks, particularly when people without healthcare expertise are doing the ranking without the full context.

To create a leaderboard that can make meaningful change, it’s crucial to understand what context matters. Otherwise, Hon said gamification might have short-term benefits but backfire in the long term as important, less-tangible factors are crowded out by overemphasizing one metric.

Case in point: Hon said he’s currently hooked on a popular puzzle game. The online leaderboard keeps him logging in long after the game itself stopped bringing much joy to his routine.

“It’s just like, what’s the point of this really? Am I just playing this game to maintain my position? Do I even really enjoy it anymore?” he said. “I probably would play it less if actually that leaderboard didn’t exist. So that is really for the benefit of the site. It’s not for the benefit of me.”