Trump called the climate crisis a scam. It could prove a gift to China.

Donald Trump and Xi Jinping at a 2017 event in Beijing

President-elect Donald Trump has long questioned the reality of the climate crisis, describing it as a “scam” and accusing policies to tackle the crisis of destroying US jobs.

Many expect him to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement to limit emissions upon taking power in January, as he did in his first term.

But his hostility to green policies conflicts with another of his priorities — challenging the rise of China.

“A second US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement would present a significant opportunity for China to expand its leadership role in multilateral climate issues,” Herbert Crowther, an analyst with the Eurasia Group in New York told B-17.

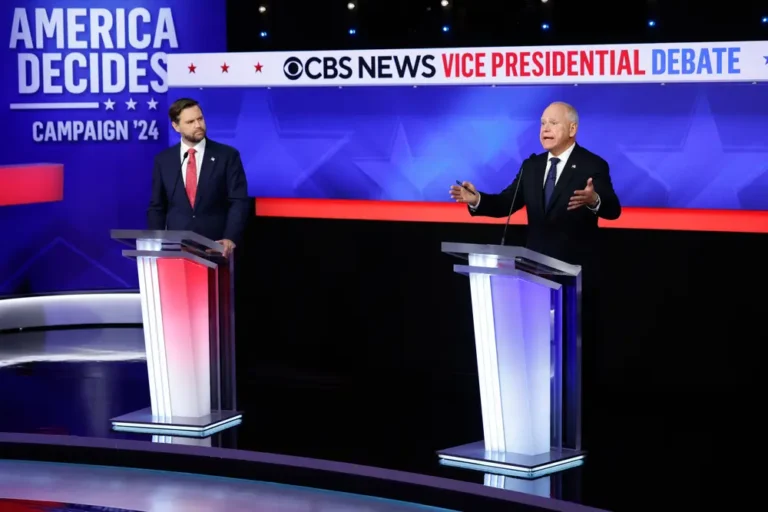

Trump’s victory is overshadowing this week’s UN climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, where pledges from Biden administration officials are tempered by the fact they won’t be around for long.

And China is already positioning itself to fill the power vacuum and build its global influence.

“In the week since the election, we’re already seeing China try to claim the mantle of global climate leadership and portray itself as the more “responsible” actor in this space,” Lily McElwee, fellow in the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, told B-17.

“Beijing is out in force at COP29 calling for the United States under Trump to engage in ‘constructive dialogue’ and highlighting China’s contributions to decarbonization through major investments in electric vehicles and other greentech industries.”

A solar thermal power plant in Gansu Province, China, in 2024

The green tech superpower

China has a curious position as both the world’s largest polluter, and a powerhouse of green technology.

It tops the rankings for greenhouse emissions, which helped power its huge economic growth in recent decades.

In 2020, President Xi Jinping pledged that China would become carbon neutral by 2060, and it’s on track this year to record its first drop in greenhouse emissions since 2016.

At the same time, China has pushed harder to produce its own green technology — and sell it to the rest of the world.

It is the world’s largest producer of electric vehicles and solar panels, and the percentage of its energy coming from renewable sources is rapidly growing.

That work brings practical and economic benefits. Analysts also point to other motives for Beijing’s green push: influence and power.

“Where the Trump administration sees renewable energy as a threat to jobs, China is leveraging clean energy as part of a long-term strategic gambit,” wrote Daniel Araya of the Brookings Institute in Washington, DC, in 2018.

China, as part of its “Belt and Road” initiative to grow its global influence, has provided developing countries with renewable energy technologies, including wind farms.

“Green tech plays a critical role in Xi’s economic vision. While China has spent a decade trying to catch up to the United States and other advanced economies in existing tech (like semiconductors), it is increasingly focused on securing leadership in emerging industries like cleantech,” said McElwee.

The strategy is paying off, with global demand for renewable energy production technologies predicted to surge, and China set to account for 60% of installed global renewable energy capacity by 2030, according to an October report by the International Energy Agency.

The US lags China as a clean tech economic power.

Trump has been explicit about his plans to repeal and otherwise roll back climate policies from the Biden administration.

That included a pledge just before the election to “rescind all unspent funds” from President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which provided billions in funding for clean tech.

Will China step up?

There are also doubts over how much China is willing to take an international leadership role on climate issues.

It’s been wary of international agreements to tackle climate change in the past, and last year was accused by European officials of obstructing G20 efforts to tackle the climate crisis, Reuters reported.

Assuming a leadership role would likely require China to send money to other countries, said Crowther.

“The key question for officials in Beijing will now turn to whether China wants to deepen its financial commitments to helping other countries—particularly emerging markets—accelerate their own energy transitions,” he said.

Crowther said the run up to next year’s COP30 summit in Brazil would provide clues of China’s intentions.

Ultimately, Xi may be more interested in cementing China’s economic advantages than in concrete diplomatic pledges.

“Although Beijing will try to boost its image as a global leader on climate change, I don’t know how much substance will follow,” said McElwee.