A homebuilder-association CEO told us the 4 obstacles keeping America from having more housing

The US is suffering from a deep shortage of homes, and it’s driving sky-high home prices and rents.

The laws of supply and demand explain it: the supply shortage — estimates of which range from 2.8 million homes to more than 7 million homes — coupled with an uptick in demand in recent years has sent prices soaring.

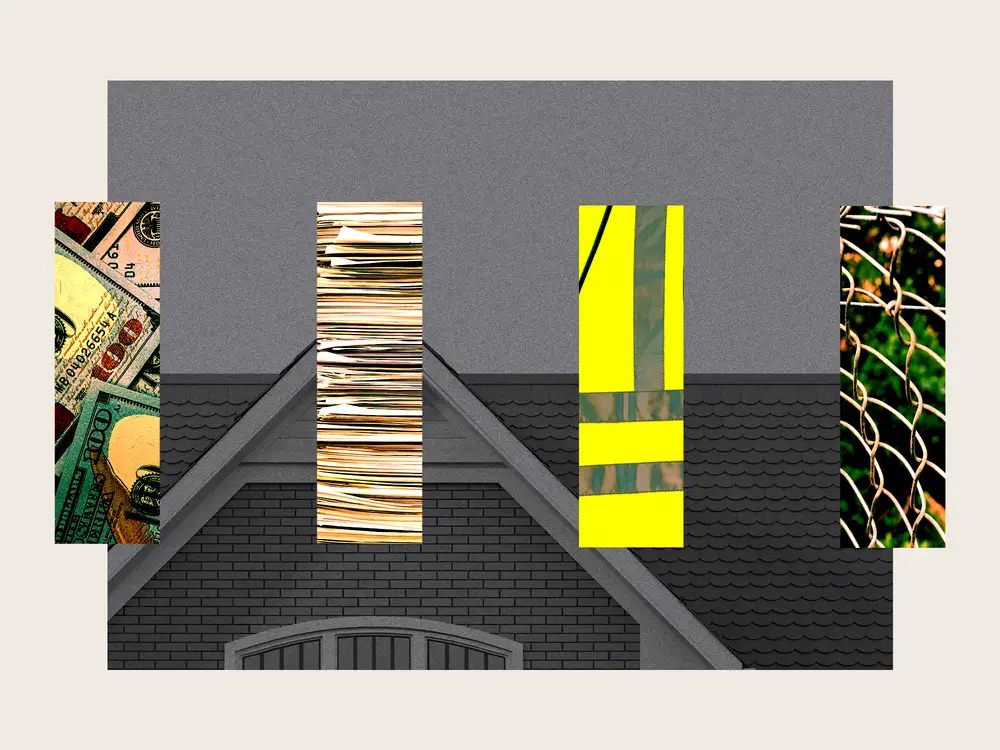

The leader of the top trade association and lobby for the home construction industry thinks there are a few key obstacles to fixing that shortage. Jim Tobin, CEO of the National Association of Home Builders, blamed the high cost of land, a shortage of skilled construction workers, burdensome government regulations, and the anti-development “Not in My Backyard” sentiment for the home shortage.

Cost of land

The cost of land — a significant portion of the cost of a home —has risen significantly in many places in recent years as its availability has plummeted, exacerbated by high demand for housing and restrictive land-use laws that prohibit dense development.

At least 75% of residential neighborhoods in many major US cities like Los Angeles, Seattle, and Chicago are zoned exclusively for detached single-family homes. This means that as demand for housing increases, these communities can’t accommodate many additional homes. As demand overwhelms the supply of land, prices rise.

“We just hear more and more that it’s harder to find affordable pieces of land to develop for housing,” Tobin said.

A worker shortage

A national shortage of construction workers — estimated at around 500,000 workers this year — has also driven up the cost of building new housing and renovating existing homes, Tobin said, noting that skilled workers in residential construction are in particularly short supply.

Fewer construction workers means less — and slower — residential construction and higher wages for workers, which in turn leads to higher home prices. The worker shortage has mounted as policymakers have emphasized college over the trades, and a wave of experienced workers retired during the pandemic, industry experts said.

Townhomes under construction are seen in a new development in Brambleton, Virginia.

Lots of regulations

Tobin also pointed out that builders face a significant regulatory burden. Rising demand for housing in recent years has run headlong into a web of local, state, and federal regulations — from restrictive single-family zoning to energy code requirements — that slow down or kill residential construction in communities across the country, he said. When it comes to housing, state and local governments control the majority of regulations that most inflate housing costs by limiting or slowing down construction, but federal regulations also play a role.

“Those delays all add up to more costs and less availability,” Tobin said. “We need all options on the table when it comes to increasing housing supply, which means allowing more density in suburbs or cities.”

‘NIMBY’ opposition

Many of these restrictive regulations are bolstered by local opposition to new housing — epitomized by “NIMBY,” or “Not in my backyard,” sentiment, Tobin said. Many local homeowners oppose new construction for the simple reason that additional housing in their community would depress their home values, he argued.

“One of the challenges we have in localities across the country are people that already have theirs, and they don’t want anybody to have theirs,” Tobin said. “We have local government officials that won’t back more housing development because they’re afraid of the backlash from local constituents.”

The future of housing

Tobin said the strength of the overall economy and interest rates will also play a major role in determining housing costs over the next few years. He expects mortgage rates to settle into a “new normal” of about 5 to 5.5% by 2026, lower than the current 30-year fixed rate of 6.79% but above the pre-pandemic average.

Looking to next year, Tobin said he expects President-elect Donald Trump to have a mixed impact on housing costs. He’s optimistic Trump will roll back some federal regulations and open up some federal land for new housing, but he’s concerned about mass deportations potentially shrinking the already scarce supply of workers, and new tariffs inflating the cost of building materials.

Tobin said he plans on working with Trump’s transition team, the new administration, and Congress to advocate for tariff policies that don’t send building costs surging. “I would certainly welcome an increase in domestic industry when it comes to building materials,” Tobin said, “but tariffs only work if that is the outcome.”