High housing costs making California more undesirable, RAND economist says

RAND economist said increasing the state’s housing supply is essential to lowering rents and making homeownership affordable.

According to RAND economist Jason Ward, the high cost of housing is keeping California families from becoming homeowners and contributing to persistent homelessness.

However, local policies and politics prevent California from building enough homes to make housing affordable.

Regulation and opposition from residents who fear that more housing will exacerbate overcrowding are among the challenges.

Also see: California has six of the most valuable housing markets in the United States.

“From a policy perspective, we treat housing as a societal bad,” Ward stated.

However, he believes that obstructing new housing is not in California’s best interests.

“What we’ve done is made it so expensive here that it’s no longer a viable or even desirable place to live for a lot of people.” “And with that comes major issues like homelessness,” Ward explained.

A more inclusive policy would make the state more accessible to a wider range of people.

Also see: Southern California tops wildfire risk rankings as insurance becomes more difficult to obtain

“You know,” Ward replied, “everyone moved here at some point.”

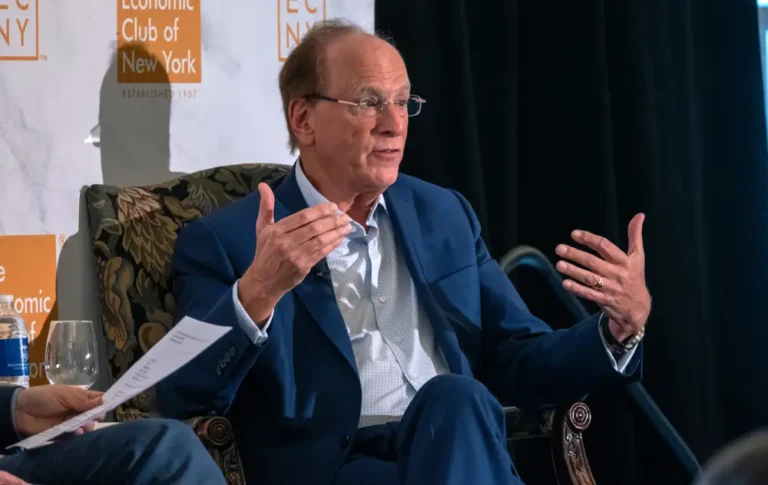

Ward, who joined the Santa Monica-based think tank in 2019, and I recently discussed the housing crisis. His remarks have been edited for length.

Q: What is California’s most pressing housing issue right now?

A: To me, the issue that connects everything is a lack of affordability.

Also see: Realtors predict rising prices and sales in 2024 despite California market decline

Both theory and evidence point to a lack of supply as the cause of high housing costs. Housing underproduction in relation to demand raises rents and home prices. … (And) the high cost of producing housing has made the production of middle-income housing largely unfeasible without significant public subsidies.

Most Californians now have no realistic path to homeownership due to rapidly rising home prices. It has also increased the stakes for existing homeowners to oppose anything that threatens the massive valuation of their homes, whether it is a new multifamily building next door or anything that might, say, increase traffic, change a view, or potentially affect anyone’s perception of value.

Underproduction in the rental market has resulted in millions of households doubling and tripling up in units too small for them, as well as skyrocketing eviction rates as COVID-era protections expire. Because housing consumes a larger portion of household budgets, any financial shock can be fatal to remaining housed, ultimately driving people into homelessness.

Q: Has there been any progress in addressing the state’s homelessness issues?

A: No, if progress means reducing the number of homeless people in any meaningful, measurable way.

According to RAND’s ongoing survey of unsheltered Angelenos, nearly three-quarters of those on the streets have been there for more than a year, and nearly half have been there for three years or more.

So we’re not even making any headway in housing people who have been homeless for years.

And we have done nothing to address the influx of people into homelessness as a result of exorbitant housing costs. We will never solve homelessness in a setting where a basic one- or two-bedroom apartment costs $2,000 to $3,000 per month and a $4,000 to $6,000 security deposit is required just to try to pay those rents.

Q: Many residents say they want their neighborhoods to stay the way they are. Is the push to build more housing endangering people’s quality of life?

A: You know, we spent decades building millions of homes, and people moved into them. Then it’s like, now that I’m here, nothing else should change.

The only thing you can really do to discourage people from coming here is to make it an extremely unpleasant place to live. However, this is not a good policy.

In some ways, I believe we’ve already done that in California. We’ve made it much less desirable to live here. Even college-educated people are starting to leave California.

So, (wouldn’t it be better) to simply accommodate the demand for housing and try to make this a place that is accessible to a diverse range of people in the future? … Everyone has moved here at some point.

Q: Which programs have proven to be the most effective thus far?

A: Los Angeles’ Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) program — a voluntary, incentive-based program that includes significant increases in density, exemption from parking minimums, and other regulatory forbearance — has been a remarkable success story that should simply be extended.

… You should not be concerned about whether (housing) is near transit and instead allow people to build housing with less parking and more units wherever they want.

Q: According to Senate Bill 9, property owners in California can subdivide lots in single-family neighborhoods and build up to four units on those parcels. Is this having an effect on the housing crisis?

A: It has yet to have a significant impact, and I doubt it will until we remove the exclusions that prevent professional builders from using this pathway.

Developers are those who construct housing. Putting a property owner in the position of having to live on their property or pay to move away for the years it can take to do even a duplex, let alone a lot split and two duplexes, automatically eliminates 95% or more of California households from being able to use this bill.

This limitation… prevents the bill from having any meaningful effect on housing production.

A: California voters rejected two ballot measures that would have eased state restrictions on rent control. Will the third time be the charm when rent control is reintroduced in 2024?

A: Only time will tell. Most Californians, I believe, understand that rent control without a significant increase in housing production will not solve many problems.

Q: Do you believe that expanding rent control is a viable solution to the state’s skyrocketing rents?

A: With enough housing production, rent control can do its intended job of preventing the worst excesses of some landlords.

However, in an environment of unaddressed housing scarcity, rent control places the entire burden of the housing crisis on landlords, and the majority of landlords are not large, corporate landlords. Inflation is real, and many business owners are struggling to make ends meet as operating expenses exceed rental revenue. This can and does have a negative impact on housing affordability.

A GLANCE AT JASON WARD

Economist and professor

RAND Corporation and the Pardee RAND Graduate School are the organizations involved.

Los Angeles is where I call home.

Bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees in economics from the University of Illinois at Chicago

Previous employment: Nearly 20 years as an audio engineer in the recording industry; teaching and research assistant at the National Bureau of Economic Research.