China’s cheap goods are threatening to undermine its influence in the developing world

Cheap Chinese goods, including electronic vehicles, textiles, and steel, are flooding countries such as Indonesia.

China is seeking to portray itself as the champion of the world’s so-called “Global South” of non-Western rising economies.

But in its quest for influence, it’s running up against an obstacle — a rising backlash to its trade practices.

From Indonesia to Brazil, cheap Chinese goods, including electronic vehicles, textiles, and steel, are flooding markets and, critics say, submerging local industries still seeking to recover from the economic downturn linked to COVID-19.

China’s exports, meanwhile, are growing at a rate of around 12% in dollar terms year-on-year, according to October trade data, with 50% being sent to the developing world.

“There is significant backlash across the developing world to Chinese trade, lending, and investment practices, a trend that has only been accelerating in post-COVID,” Charles Austin Jordan, a senior research analyst on Rhodium Group’s China Projects team in Brussels, told B-17.

So far this year, Brazil has slapped 35% tariffs on Chinese fiber optic cable, as well as 25% on steel and iron imports, while Indonesia has imposed 200% tariffs on Chinese textile imports.

Thailand, for its part, has established a special government committee to clamp down on Chinese imports after the closure of hundreds of domestic factories, while Peru and Mexico are also imposing anti-dumping measures on Chinese steel.

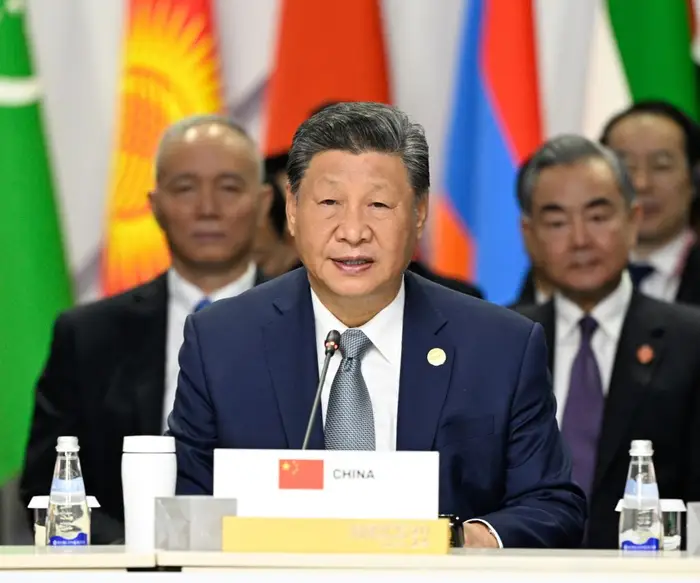

Xi Jinping at the BRICS summit in Russia in August 2024.

China brokers trade ties in the developing world

In recent decades, wealthy Western economies have been accused of neglecting their economic and diplomatic ties with the developing world, and China has happily stepped into the gap.

As part of its “Belt and Road” economic initiative, China has invested billions of dollars in infrastructure projects in Africa, South America, and Asia, growing its political and economic influence.

Meanwhile, consumers in the developing world have benefited from the influx of affordable Chinese goods.

“Undoubtedly, this has been a huge boon to these countries in the short run,” said Jordan.

Yet closer integration with the Chinese economy is coming at a cost.

As the economies of developing nations become woven more tightly with China’s, the volume of cheap Chinese imports has increased.

And the flood of imports is holding back local industries, some of which are seeking to occupy parts of the global economy they expected China to vacate as it became more advanced, according to a recent report by the Rhodium Group.

The report pointed to areas such as textile and steel manufacturing.

Mingda Qiu, a senior analyst at the Eurasia Group, told B-17 that developing countries would prefer promises from China to invest and build up domestic supply chains, rather than simply “flooding their markets with cheap goods.”

“China’s practices are depriving these countries of benefiting from the very model China used to ascend global value chains,” said Jordan. “Industries simply can’t compete with the deluge of subsidized Chinese products.”

At the same time, critics of Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road’ project are calling on developing nations to resist Chinese influence.

Jonathan Ward, a senior fellow at the Hudson Center in Washington, DC told B-17 that “developing nations still have the opportunity to retain their sovereignty, economic freedom, and future prosperity — if they push back against the Chinese Communist Party in concert with the United States and if other major economic centers and alternative partners in growth rise across the developing world.”

A worker on a Chinese-funded harbor project in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 2024.

China’s dilemma

China has shown no sign of reducing the size of its manufacturing base, or of relinquishing its dominance of global export markets.

Partly, this is because of its own domestic economic woes.

As such, China is counting on its manufacturing and export base, which has long been the core of its economic power. In recent years, it has also been expanding to dominate green technology markets such as solar panels and electronic vehicles.

“China views its position as the center of global value chains as a strategic advantage, and the massive export-oriented manufacturing base provides immense economic benefits in terms of stable employment and technological upgrading,” said Jordan.

He added that China believes it can withstand pressure from the West and “thwart retaliation from the developing world” by leveraging its economic and political heft. “There is a high degree of confidence that exports will continue to be a reliable source of growth,” he said.

In the meantime, the growing rift with advanced Western economies has made China’s exporters more dependent on developing markets.

“The linchpin of China’s efforts to offset growing pushback from advanced industrial democracies is increased economic engagement with developing countries,” said Ali Wyne, a senior researcher with the Crisis Group in Washington, DC.

He added: “As such, it will face growing pressure to ensure that its exports do not become more of an irritant in its relations across Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia.”

There are signs that China is seeking to adapt, emphasizing “small but beautiful” infrastructure projects focused on sustainability and boosting local economies, as well as showcasing a zero-tariff trade policy with some African nations during a summit in September.

Yet the importance it places on its status as a manufacturing powerhouse, and the relative weakness of domestic Chinese demand, means the flow of cheap Chinese goods abroad is unlikely to let up anytime soon.

“Domestic underconsumption and mounting trade tensions with developed countries mean that there is no self-evident solution to its present challenge,” said Wyne.