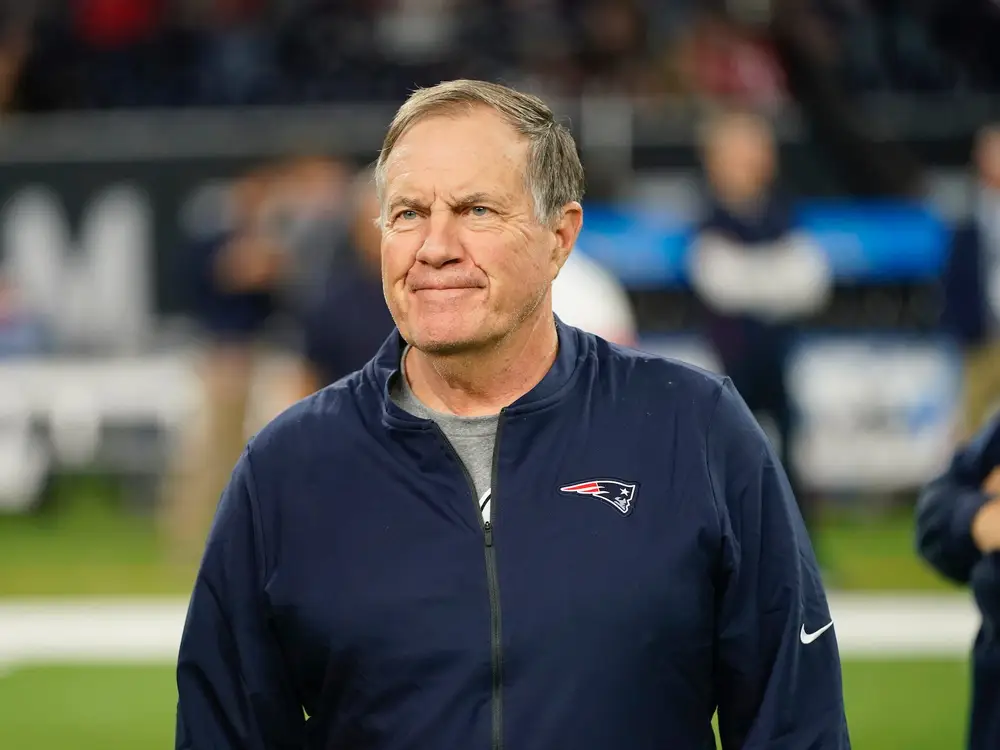

Bill Belichick’s shocking move to coach UNC shows how college teams are looking more like the pros

Revered football coach Bill Belichick’s departure from the NFL says a lot about the ascendance of college football amid lucrative sponsorships in the era of the transfer portal, fast-growing NIL opportunities, and revenue sharing within the NCAA.

Word on Wednesday that the eight-time Super Bowl champ signed a five-year agreement to serve as head coach of the University of North Carolina Tar Heels rocked the sports industry.

“We are embarking on an entirely new football operation,” UNC Athletic Director Bubba Cunningham said at a press conference Thursday. He said Belichick’s pro experience played a factor in his hire. “The future of college athletics is changing, and we want to be in the forefront of that.”

Belichick will be pocketing $10 million a year — plus the opportunity for performance-based bonuses, according to a term sheet outlining the deal.

Of course, college sports — and especially football — have always been big business. But recent changes underline the move toward allowing more money to flow into programs and athletes, and further professionalize what is still considered amateur athletics.

Scott Fuess, Jr., a professor of business at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln who studies the economics of college sports, told B-17 that Belichick’s hire is “a very obvious, public-facing signal” of how college football is becoming more like the pros.

“What we’re doing is we’re NFL-izing collegiate football,” he said.

Another indicator of the shift in college sports? More schools are hiring general managers for their football programs, Fuess said. Their focus is on bringing in talent and financing it, something that’s all the more important in the name, image, and likeness — or NIL — era. NIL allows players to be paid by brands and other sponsors for the use of their name, image, or likeness.

Fuess said that in the upper ranks of collegiate football — specifically within the power conferences — “you’re going to see arrangements that look more like NFL programs.”

Belichick’s move is part of a bigger trend

Belichick’s hire isn’t the only signal that managing a college sports team is looking a lot more like managing a pro team.

In September, longtime ESPN reporter Adrian Wojnarowski left the outlet to become general manager of the men’s basketball program at St. Bonaventure University — where he went to school — to work on NIL deals and recruiting.

And Belichick will be getting some help at UNC from Michael Lombardi — a sports host and former NFL exec who said Wednesday night that he’ll serve as the general manager of the Tar Heels program.

For Belichick, there are family ties to UNC. His father was an assistant football coach for the Tar Heels in the ’50s. And The Guardian’s Ollie Connolly, citing anonymous sources, reported last week that as part of his deal, Belichick sought a guarantee that his son would succeed him as head coach — which he reported that UNC is open to.

Patrick Rishe, executive director of the Sports Business Program at Washington University in St. Louis, told B-17 that Belichick’s move doesn’t necessarily portend an exodus of NFL coaches to college towns because Belichick’s situation was unique.

“I don’t think Alabama or Ohio State are going to be recruiting Andy Reid away from the Chiefs,” he said, referring to Kansas City’s head coach.

Still, Rishe said, his move is a reminder that coaches are free agents just as players are.

Rishe said one of the biggest forces animating college football’s bulk-up is money flowing from NIL collectives. He said collective money, already used to recruit players, could also be directed toward bringing on coaches.

The collectives gather money from donors and distribute it to players. For example, at Fuess’s University of Nebraska, the 1890 Initiative — its resident, independent NIL collective — raises money for athletes in exchange for donor perks like merch and invites to membership events. Its website says it partners with athletes “to help them build personal brands through athletic endorsements, brand partnerships, and NIL compliance protocols.”

An expanded job

Fuess said that until recently, college athletes were limited in transferring to other programs. Now, that’s no longer true because of the transfer portal window, which in October was reduced for Division I football and basketball players to 30 days. Because of that, he said, college coaches must work harder than ever to keep players happy.

“Their free agency is freer than in professional sports right now,” he said, referring to college players.

Fuess, who also serves as his campus’s faculty representative to its athletic department, said college coaches increasingly have to know how to spot talent, how to pay for it, and how to keep it.

That means there could be more people who come from the NFL, though they could also come from elsewhere in college athletics, he said, because the cultures of the NFL and college football are different. Plus, there’s also NCAA revenue sharing in the wings, where, beginning next academic year, schools are expected to be able to share athletic department revenues with student-athletes.

“Collegiate sports is a little bit more of a wild wild west than the very buttoned-down world of the NFL,” Fuess said.

He said that some college football programs seeking to ascend to the top or remain there are likely to do so by demonstrating big funding commitments or making high-profile hires.

Fuess pointed to a statement days ago by Purdue University President Mung Chiang introducing the Boilermakers’ new football coach, Barry Odom, that the university would “invest more than ever before in athletics.”

A hire like Belichick represents a similar move, Fuess said.

“Everybody knows his name. Everybody knows his coaching success. Everybody knows about him,” he said.

If you want to remain a high-profile program, Fuess said, “you’re going to want to demonstrate as best you can that you are committed to doing this.”