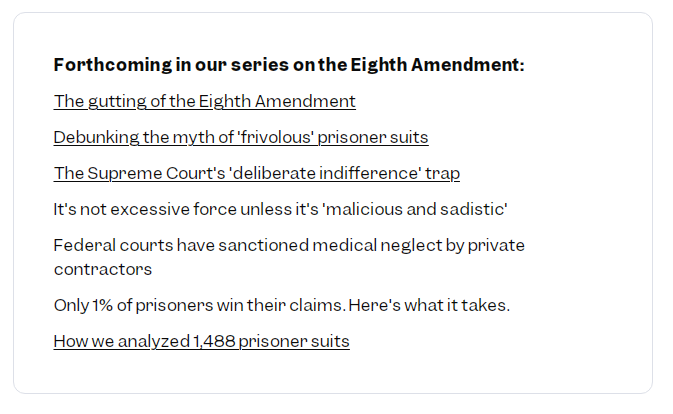

The myth of frivolous prisoner lawsuitsHow a Clinton-era law, the PLRA, hollowed out the Eighth Amendment.

Juanita Ornelas, a Texas prisoner, filed a lawsuit in 2018 claiming the state had failed to protect her from repeated sexual assaults; she presents as masculine in prison for safety reasons. A federal judge dismissed the case.

Nearly three years into Bill Clinton’s first term as president, US senators took to the floor to tackle an urgent concern. Prisoners across the country were filing too many lawsuits.

“The vast majority of these suits are completely without merit,” Sen. Orrin Hatch, the Republican chair of the Judiciary Committee, said in September 1995. “It is time to lock the revolving prison door and to put the keys safely out of reach of overzealous federal courts.”

Sen. Harry Reid, who would go on to become the Senate Democratic majority leader, ticked off a litany of ridiculous cases he said were clogging up the nation’s courts. There was the Missouri prisoner who sued because his facility didn’t have salad bars on the weekends. And the Nevada prisoner who said his constitutional rights had been violated when he received chunky peanut butter — not smooth — from the prison canteen.

“And to think, we, the taxpayers, are paying for all of this,” Reid said.

Reid and Hatch were speaking in support of the Prison Litigation Reform Act, introduced by the most powerful man in the Senate at the time, the Republican Bob Dole. Dole, then the majority leader, had pitched it as a common-sense reform that would sharply curb such “frivolous lawsuits.” Hatch insisted it wouldn’t affect prisoners who raised legitimate claims.

The National Association of Attorneys General helped craft the legislation and circulated top-10 lists of “frivolous” prisoner lawsuits, including the complaints about salad bars and peanut butter, to garner support. A few attorneys general — from red and blue states alike — took their case to The New York Times. “We feel strongly that convicted criminals should not be granted unlimited free access to our courts to conduct their costly and most often frivolous lawsuits,” they wrote.

“It was about resources,” a former attorney general who backed the legislation said. “You are just struggling to run what was then the state’s largest law office. So to me it was a question of degrees. Let’s find some balance and look at cases that need to be looked at and get rid of steak and wine and peanut butter cases.”

Some elected officials issued warnings. Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts called the bill “patently unconstitutional,” and Joe Biden, then a Delaware senator, said it placed “too many roadblocks to meritorious prison lawsuits.” But it passed easily, buried in an omnibus appropriations bill, with little legislative debate about its potential repercussions.

In April 1996, Clinton signed the PLRA into law.

A separate system of justice

While it had never been easy to file a lawsuit from prison, the rules of play had been roughly the same as for any other indigent person seeking redress in court. The PLRA changed that, effectively carving out a separate and unequal system for prisoners.

Prisoners could now win monetary damages only if the harm they endured was physical, rather than mental or emotional. Strict caps on attorney fees discouraged lawyers from representing prisoners, leaving the vast majority of plaintiffs, many without a high-school diploma, to file on their own.

Many prisoners would no longer get their day in court: A judge or staff attorney would screen cases before any evidence could be presented or any motions could be made. If the screener deemed a case frivolous or decided it had failed to clearly state a constitutional claim, the judge could simply dismiss the case. A prisoner who had three suits dismissed in this way — the “three strikes” rule — would be barred from filing another without paying prohibitive court fees.

Crucially, any claims that made it to court would be dismissed if a prisoner could not show they had exhausted their prison’s internal grievance process — procedures that a number of state corrections departments have turned into arcane, highly technical affairs.

“In a busy court, there’s a template to get rid of the cases,” Nancy Gertner, a former federal district judge in Massachusetts, said of the PLRA, “and invariably they’re gotten rid of.”

The senators were right that there had been an uptick in prisoner lawsuits. But that increase closely tracked the rise of the prison population as the war on drugs and punitive sentencing laws more than doubled incarceration rates from 1986 to 1996, the year the PLRA became law.

Reid had compared prisoners to “an alcoholic locked inside a liquor store,” abusing the nation’s legal system with easy access to the courts. But legal scholars have found that the rate of prisoner legal filings had actually stayed relatively consistent.

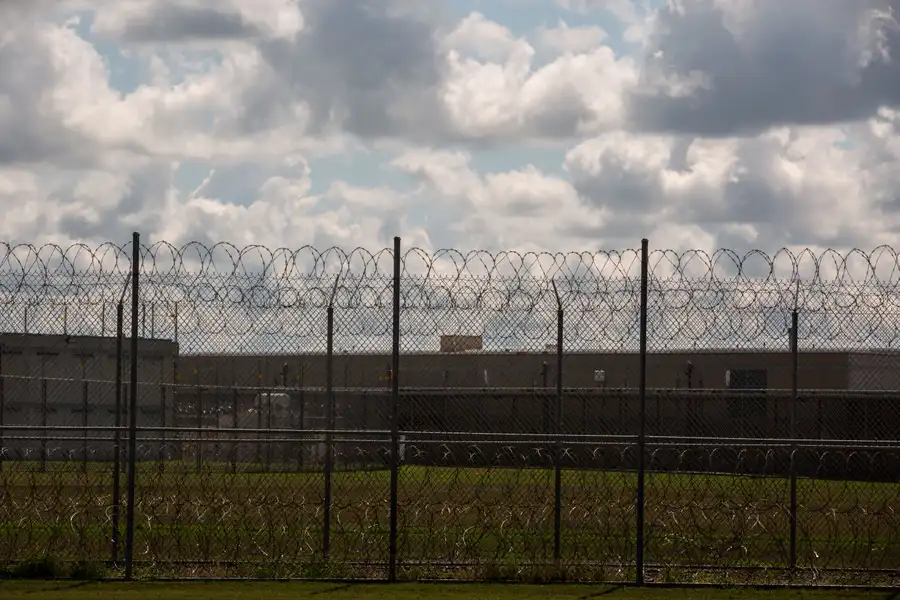

The William G. McConnell Unit in Beeville, Texas, where Ornelas is incarcerated. She lost her Eighth Amendment case because a judge decided she had failed to properly submit grievances before filing suit

In fact, Margo Schlanger, a law professor at the University of Michigan, found that in the year before the PLRA was signed into law, prisoners filed a similar number of lawsuits per capita as people on the outside.

Within five years of its passage, prisoner suits dropped by 43%, even as the prison population continued to grow, according to Schlanger’s research. Schlanger examined prisoner filings again in 2022 and found that the filing rate never rebounded.

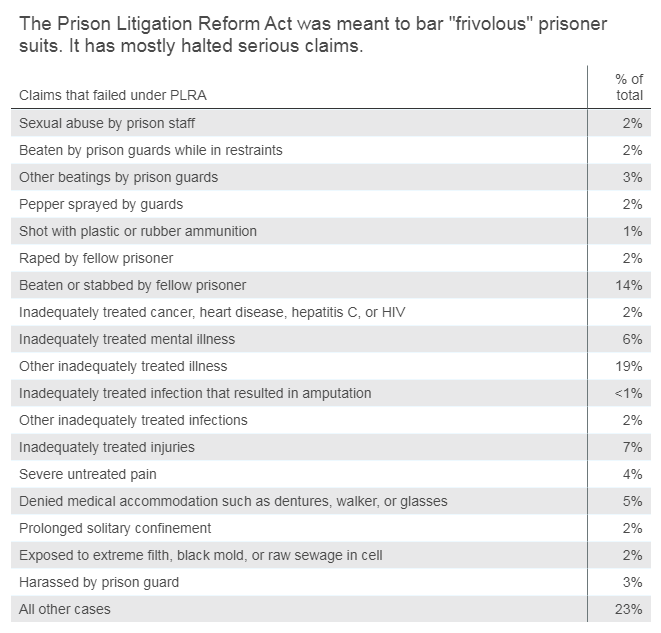

Cases that prisoners have filed since the law’s passage, she found, have struggled to succeed. To understand why, B-17 analyzed a sample of nearly 1,500 federal cases alleging “cruel and unusual punishments” in violation of the Eighth Amendment, including every appeals court case we could locate with an opinion filed from 2018 to 2022 citing the relevant Supreme Court cases and standards.

Some were filed by former prisoners after their release, or by their families, who were not bound by the PLRA. But in an examination of the roughly 1,400 cases filed by people while they were imprisoned, the impact of the PLRA jumped out — 27% of those cases failed because of the law’s requirements.

In B-17s district court sample, the PLRA’s effects were more dramatic — 35% failed because of the law.

A few dozen of the claims B-17 examined appeared to center on minor matters: For instance, an Indiana prisoner claimed he developed a rash after he wasn’t allowed to shave, an Alabama prisoner said he was served undercooked food, and a Michigan prisoner sued saying he’d been denied shoes while being held in a dirty shower. But the vast majority clearly involved claims of substantive harm. Among them were dozens of claims that prisons had allowed retaliatory beatings, stabbings, sexual assaults, and egregious forms of medical neglect.

These include the case of Kenneth Coleman, a Florida prisoner. He said prison officials put him in the same cell as an “enemy” who later assaulted him, leaving his left eye with a sag. He lost his case for failing to complete the prison’s grievance process before filing suit. They include a case out of Colorado, in which the plaintiff said she began self-mutilating after medical providers failed to dispense the hormone blockers that had been prescribed to treat her diagnosed gender dysphoria; her case was dismissed because the court ruled that self-harm didn’t count as a physical injury. And they include the case of Benjamin Gottke in Louisiana, whose left leg was amputated below the knee after, he said, corrections officials failed to protect him from being assaulted. His case was dismissed at screening for failure to properly state his legal claim.

The Louisiana and Colorado corrections departments declined to comment on the record. A spokesperson for the Florida Department of Corrections did not comment on the Coleman case but said, “We ensure the safety and healthcare of our inmate population in accordance with Florida law.”

When prisoners’ cases are knocked out by the PLRA, they rarely succeed on appeal. Such appeals, B-17 found, failed nine out of 10 times.

Victor Glasberg, a civil-rights attorney in Virginia, has represented prisoners for decades and successfully litigated an Eighth Amendment case about conditions on the commonwealth’s death row. “The Prison Litigation Reform Act is the worst piece of federal legislation to have been enacted in my lifetime, and I was born in 1945,” he said. “It is malicious, vindictive, and grossly unfair.”

An undiagnosed tumor

Kevin Harrison Jr. was 24 years old and not long into a life sentence for murder when he first noticed lumps on the left side of his chest. In July 2011, he saw Michael Hakala, a doctor at Southeast Correctional Center in Missouri who worked for a prison healthcare company called Corizon Health, now YesCare, which was then contracted to provide healthcare to the state’s prisoners. In a civil complaint he would later file, Harrison said Hakala assured him that the lump was benign without ordering a biopsy.

Two years later, the lumps had grown considerably, Harrison’s complaint said. During shirtless basketball games, he said, other prisoners told him he looked as if he’d been shot.

Harrison said Hakala again assured him that nothing was wrong.

More than seven years after his first appointment, in November 2018, Harrison said he was granted a visit with another doctor; that doctor also worked for Corizon. Concerned by what had become a gnarled mass, the doctor ordered a biopsy. At 31 years old, Harrison was told he had a rare form of skin cancer.

He underwent what he described as a grueling, invasive surgery that required doctors to cut deep into his pectoral muscle to remove the tumor. He wore a bandage for months as his chest slowly healed, and he lived with debilitating pain. Several years later, the muscle pain and spasms have barely abated, he said, and with his follow-up appointments often delayed he worries the cancer will return.

In March 2022 he filed suit against Hakala and other medical staff alleging that they had violated his constitutional rights by failing for years to biopsy his tumor.

His case was dismissed during screening.

Patricia Cohen, a magistrate judge for the Eastern District of Missouri, found that his handwritten complaint, filed without counsel, had failed to make a clear Eighth Amendment claim: He hadn’t shown he could prove the defendants had intentionally delayed his treatment.

As in many claims dismissed at screening, the judge gave Harrison 30 days to file an amended complaint. In this case, a court clerk, Nathan Graves, said Cohen had provided Harrison with “clear instructions” for how to do so. Harrison, whose request for an attorney was denied by the judge, told B-17 he missed the deadline because he was locked in solitary confinement for assaulting two corrections officers. He refiled the case last year, which is still pending; the defendants have yet to respond to the underlying claims.

Tad Eckenrode, Hakala’s attorney, declined to comment on the pending litigation but noted that Harrison’s claims remained unproven allegations; the Missouri Department of Corrections declined to comment. A YesCare spokesperson declined to speak about Harrison’s case but said by email, “Our industry is filled with mission driven professionals who are committed to serving incarcerated individuals, many of whom have never received healthcare in their life, within a challenging prison environment,” adding that “ignoring the many successes and positive advancements in our industry only serve to make it more difficult to retain and recruit medical professionals to serve incarcerated populations.”

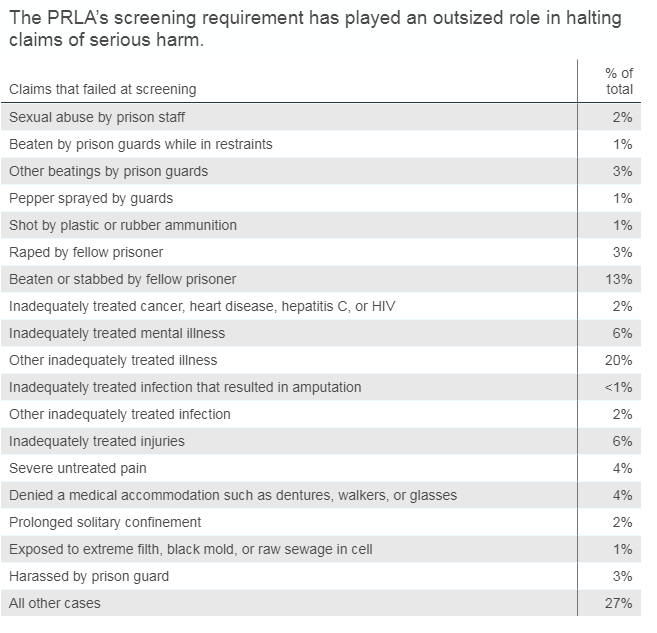

Of the 376 cases in B-17’s sample disqualified by the PLRA, 75% were dismissed at screening, denying the plaintiffs the chance to argue their case in court — or seek discovery. Over half of those cases involved allegations of inadequate medical care, including several for potentially fatal illnesses, such as Harrison’s cancer.

“As a result of the PLRA, people who have suffered horrific harm, people who have extremely meritorious and compelling cases, get thrown out of court for reasons that have nothing to do with the merits of their case,” said David Fathi, the director of the National Prison Project at the ACLU. “It just tilts the playing field against prisoners across the board.”

Several cases in B-17’s sample dismissed at screening involved claims that negligence had left prisoners with permanent disabilities. A Kansas plaintiff said one of his feet was amputated after an infection was allowed to fester; a prisoner in California said he was left with persistent migraines and dizziness after a guard, while trying to quell a fight between two other prisoners, shot him in the head. Eight prisoners who alleged that they’d been sexually assaulted had their cases dismissed at screening.

The Kansas Department of Corrections declined to comment; a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation did not address the shooting claim but said the department had “fundamentally reformed its approach to addressing allegations of staff misconduct to enhance staff accountability and improve transparency.”

A ticking clock

Prisons are hierarchical systems, largely insulated from the outside world, where corrections officers control every aspect of a prisoner’s life. The PLRA effectively requires prisoners experiencing abuse or neglect to confront those officers directly, mandating that they pursue grievances internally before they have the right to seek redress in court. Prisoners in multiple cases said that requirement came with consequences.

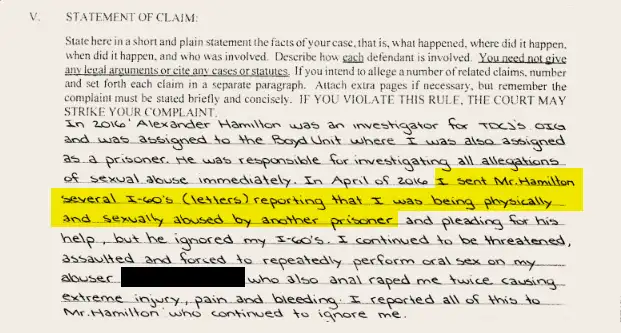

In the spring of 2016, a Texas prisoner named Juanita Ornelas began a prolonged battle with the prison bureaucracy. Ornelas, a transgender woman who said she presents as masculine in prison for safety reasons, said she was being repeatedly sexually and physically abused by another prisoner at the William R. Boyd Unit in East Texas.

The William R. Boyd Unit in Teague, Texas, where Ornelas said another prisoner repeatedly sexually assaulted her.

Ornelas, who was serving time on weapons charges, was required by Texas corrections policy to try to resolve the issue informally and then to submit a formal grievance, on a specified form, all within 15 days of the incident. The unit’s grievance coordinator would then have at least 40 days to respond, at which point, if Ornelas wasn’t satisfied, she would have another 15 days to file an appeal.

In a complaint that she would later file in the Western District of Texas, Ornelas said she had been terrified her attacker would kill her if she filed a grievance. She said that she had witnessed attacks on other people who had filed grievances and that it was common knowledge that officers at Boyd often ratted out prisoners who disclosed sexual abuse. When Ornelas finally asked an officer for a grievance form, she said in a memorandum she introduced in court, the officer refused and instead told her to stop snitching.

Desperate for help, she said, she instead submitted several I-60s — a form Texas prisoners use for routine transfer requests — to Alexander Hamilton, an investigator in the criminal justice department’s office of the inspector general who had once visited the unit. Ornelas thought if she reported the assaults directly to Hamilton, she would have a better chance at getting moved out of danger.

But her I-60s to Hamilton went unanswered and the abuse continued, she said.

Amanda Hernandez, a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, said that Ornelas’ claims were investigated and could not be substantiated and that “the agency takes all allegations of abuse seriously,” promptly forwarding them to the appropriate authorities. The office of the Texas attorney general, which represented Hamilton, did not respond to queries.

Ornelas’ handwritten legal complaint accused a state inspector general of ignoring several letters detailing allegations of sexual abuse.

In early June 2016, officials moved Ornelas to a different prison. It had nothing to do with the rape allegations, she told B-17; she’d been accused of housing a weapon in her cell, though she said it wasn’t hers. There, 200 miles away, she submitted a series of grievances to document the abuse she said she experienced at Boyd. Even then, Ornelas said in her memorandum, officials repeatedly refused to process the forms or said they hadn’t received them. In January 2017, she said — nine months after she had sent her first I-60 to Hamilton and four months after she went on a hunger strike — a grievance form was finally processed.

“I couldn’t believe it was so hard to report something like that,” Ornelas said. “They just completely ignored and disregarded the sexual-abuse report.”

A year later, Ornelas filed a pro se lawsuit alleging that Hamilton had violated her Eighth Amendment rights by failing to protect her from repeated sexual assaults. Though Ornelas said the rapes were so violent they left her bloodied, the attorney general never weighed in on the underlying claims in court, focusing on Ornelas’ failure to meet the deadline for submitting a prison grievance before filing suit; a district judge, Alan Albright, agreed with that assessment and dismissed her case. On appeal, the 5th Circuit ruled that even if Ornelas had followed prison protocols, she’d still lose the case: She had offered no proof that Hamilton ever saw or received the letters.

The offices of Albright and the other federal judges who presided over cases decided in this story declined to comment, didn’t respond to interview requests, or, in the case of Cohen, the judge in Missouri, said the decisions spoke for themselves.

Though Ornelas says she submitted sexual-assault complaints to a Texas prison official, an appeals court found that she’d offered no proof that the official ever saw or received them.

‘Byzantine grievance processes’

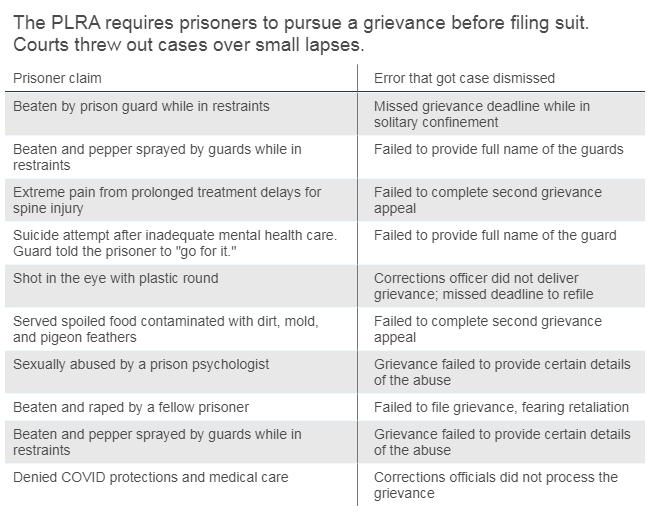

The requirement to exhaust a prison’s internal grievance system before filing suit is one of the PLRA’s most significant obstacles. Of the prisoner cases knocked out by the law in B-17s sample, nearly one in four failed because judges decided the plaintiff had not fully complied with the grievance process.

“The exhaustion-of-remedies requirement definitely incentivizes prison systems to create Byzantine grievance processes,” Corene Kendrick, the deputy director of the ACLU National Prison Project, told B-17. “If you fail to meet a single deadline, or if you worded something in a way that wasn’t quite specific enough, the courts will often just throw the cases out.”

Legal scholars have described prison grievance procedures as something out of Kafka.

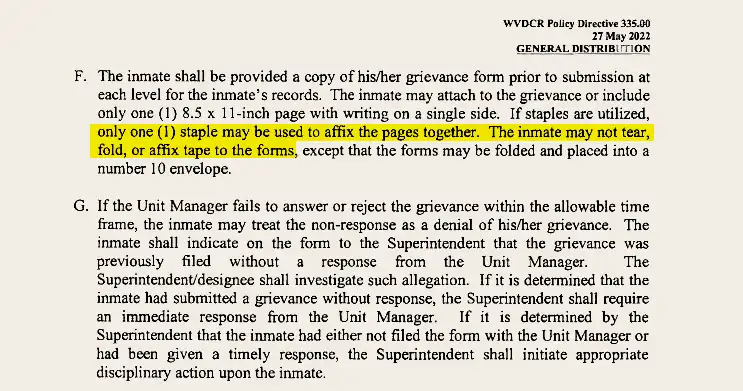

In Colorado, for instance, a grievance can be denied if the handwriting is deemed illegible or if the prisoner uses more than “one line of dialogue” to describe the abuse allegation. In Florida, a grievance can be rejected if more than one issue is discussed in a single form. In West Virginia, only one staple may be used to attach the pages.

Many states require prisoners to use an official grievance form, which prisoners sometimes depend on corrections officers to supply. Once filed, the form may go into oblivion.

“A lot of times, especially in segregation, you give the grievance to an officer,” one West Virginia prisoner told B-17. “Nine times out of 10 it’s going in the garbage.”

Andy Malinoski, a representative of the West Virginia Department of Commerce, responding on behalf of the state corrections division, said the agency “adamantly denies” the prisoner’s claim and “is committed to the safety, quality of life, and well-being of those in the care of the legal system in our state.”

Tiffany Yang, an assistant law professor at the University of Maryland, authored a study last year finding that the PLRA had effectively provided a playbook to prison systems on how to narrow the pathway to judicial relief. She documented instances in which state corrections departments had responded to a successful prisoner lawsuit by amending their grievance requirements to make the rules more complex. She called this cycle the “prison pleading trap.”

“Each prison system can define its own internal grievance procedure, and that decision has created a system that is designed to fail the very people that it should protect,” Yang told B-17. “Even if an incarcerated person is successful in overcoming administrative exhaustion, what prison officials can do with that defeat is to transform it into a blueprint for how to amend the grievance policy to make it more difficult for future litigants.”

Prison grievance procedures often have very specific requirements, such as this one from West Virginia that says prisoners are prohibited from using tape and may use only one staple.

In her study, Yang discussed a 2005 case in Arkansas in which the courts allowed a prisoner to move his case forward against medical staffers he said had denied him dental treatment, ruling that they were identifiable even though his grievance listed only their job titles, not their names. The state corrections department then updated its procedures to require all Arkansas prisoners to specify, in their first grievance, the full names of each individual involved. As Yang wrote, that alone can prove to be an impossible hurdle in situations in which officials don’t wear name badges, hide their badges, or refuse to provide their names to prisoners.

The Arkansas Department of Corrections did not respond to queries.

In a 2022 legal brief, the ACLU joined with other civil-rights groups in arguing that because prison administrators design the procedures that prisoners must follow before suing them, there is “a perverse incentive to make grievance processes as impenetrable as possible.”

The statute of limitations for civil suits is typically measured in years. But most prisoners must file a grievance on a much tighter timeline. In Louisiana, prisoners are encouraged to seek an informal solution and then have three months to file a grievance. In Arizona, they have 10 days to make an informal complaint and then five days after that to file the formal grievance. In Michigan, they have two days to resolve the issue informally and then five days after that to submit a grievance form. If they don’t file on time, they can’t win in court later.

Even when an incident has left a prisoner consigned to the hospital or solitary confinement, the clock can continue to tick.

A former Minnesota prison lieutenant told B-17 that, at the facilities where she worked, “a fairly high percentage” of prisoners had no idea how to navigate the grievance process. She said that prisoners were alerted to its existence, but only through a “two-second conversation” during intake. Prisoners at facilities in several states told B-17 they were never instructed by staff on how to properly complete these forms, and instead relied on rare visits to the library or on fellow prisoners — untrained jailhouse lawyers — for guidance.

“I couldn’t believe it was so hard to report something like that,” Ornelas said. “They just completely ignored and disregarded the sexual-abuse report.”

Paul Schnell, Minnesota’s corrections commissioner, said the department continually tries to improve its grievance system. He expressed surprise at the lieutenant’s claim, “given the number of grievances we get.”

“If the door is closed for people, that’s not OK,” he said. “We want to make sure people have a mechanism” for exercising their due-process rights.

In any case, filing a grievance comes with risks. The risk of retaliation from other prisoners and staff, as Ornelas feared in Texas. Or the risk of formal punishment. In some states, such as Alaska, officials can hand down disciplinary action if they believe a prisoner has abused the grievance system.

Again and again, a law meant to end frivolous prisoner lawsuits has halted Eighth Amendment claims on technicalities regardless of the underlying merits of their case. Many were thrown out over missed grievance deadlines; others because a prisoner failed to provide the full name of a staffer or use the proper terminology in stating their claim.

Unintended consequences

From the moment it was enacted, the PLRA faced intense criticism. In testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee in September 1996, an advocate for incarcerated teenagers warned that the law “contains several provisions that hinder efforts to protect children from danger and abuse” in juvenile institutions; the American Bar Association admonished Congress for passing a law that it said contained “unconstitutional” provisions.

David Keene, as chair of the American Conservative Union, called for the law to be reformed, saying in a 2008 op-ed article that “it had the unintended consequence of virtually insulating prison officials from external oversight.” In 2014, the United Nations’ Committee Against Torture expressed concern that the law was “curbing prisoner lawsuits at the expense of inmates’ rights.”

One of the most sustained efforts at reform coalesced in 2007, more than a decade after the PLRA was signed into law. The bipartisan SAVE Coalition rallied behind a bill introduced by Rep. Bobby Scott of Virginia that sought to ease some of the law’s most onerous requirements. “It needed reform because there’s so many instances where legitimate claims couldn’t be heard,” Scott told B-17. “On the meritorious cases, prisoners just don’t have rights.”

Rep. Bobby Scott sought, unsuccessfully, to amend the Prison Litigation Reform Act. His bill never got a floor vote.

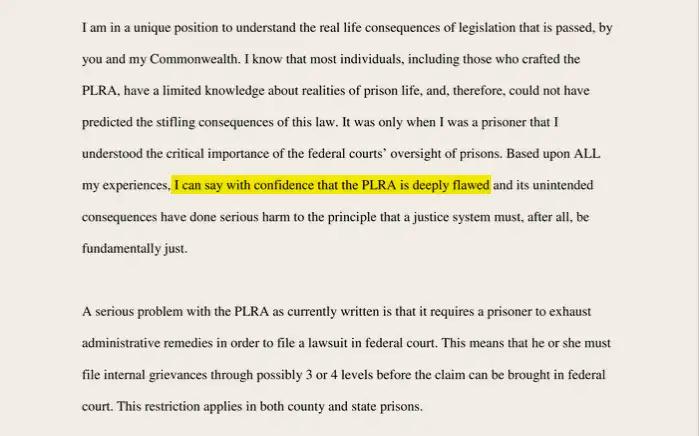

Those who testified on behalf of the bill included a retired federal judge who said the PLRA “unnecessarily constrains the judge’s role, limiting oversight and accountability”; a former director of the California prison system, who said the legislation created “often-insurmountable obstacles” for prisoners; and a former Republican attorney general who, after himself spending time in prison for mail fraud, called the PLRA a “deeply flawed” law that “undermines the protection of constitutional rights that all Americans, including prisoners, share.”

Sarah Hart, as an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia, had assisted Congress in drafting the PLRA and testified against the proposed reforms, arguing that “the current system allows corrections managers to learn of serious problems in the prison, take prompt action to stop them, and remedy past problems.”

Keene, who went on to serve as president of the National Rifle Association, told B-17 that one of the reasons he took up criminal-justice reform was that his son had spent time in a federal prison. During testimony before the House Judiciary Committee in 2007 in support of Scott’s bill, Keene said it was impossible for his son to properly file grievances, accusing prison officials of intentionally giving him the wrong forms and of reading his confidential legal mail. “The process is broken,” he said, quoting a letter his son wrote from prison. “It feels like I’m playing poker in a rigged game.”

After spending time in prison himself, a former Pennsylvania attorney general, Ernest D. Preate Jr., testified in 2008 that the Prison Litigation Reform Act was “deeply flawed.”

In their March 1995 letter in The New York Times, the state attorneys general insisted that the PLRA wouldn’t block meritorious cases, that “no reasonable individual would accept that cases of sexual assault by prison guards or unchecked and rampant tuberculosis within the prison population should be dismissed or disregarded as nonmeritorious.”

On the contrary, in the decades since the law was enacted, many prisoners accusing guards of assault have had their cases blocked by the PLRA. In B-17’s sample, PLRA technicalities likewise knocked out cases involving allegations of sexual harassment by a corrections officer, delayed treatment for hepatitis C, and prolonged stints in solitary confinement.

Just months after the PLRA became law, Jon O. Newman, a federal judge on the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, authored an article in the Brooklyn Law Review. In it, he examined the three lawsuits attorneys general cited as frivolous in their New York Times op-ed, at least two of which made their way onto the Senate floor. He found that the Nevada prisoner hadn’t filed suit because he preferred chunky peanut butter over creamy. He sued because he said that the commissary had charged him $2.50 for the jar — nearly a week’s wages for a prisoner — and that he never received the item. “I readily acknowledge that $2.50 is not a large sum of money,” Newman wrote. “But such a sum is not trivial to the prisoner whose limited prison funds are improperly debited.”

The Missouri prisoner who was ridiculed for wanting a salad bar, meanwhile, had filed suit with dozens of other prisoners alleging major deficiencies at their facility, including insufficient food, meals contaminated by rodents, a lack of proper ventilation, and dangerous overcrowding that the plaintiffs said had resulted in the housing of healthy people together with those with contagious diseases.

“The prisoners’ reference to salads was part of an allegation that their basic nutritional needs were not being met,” Newman wrote. “The complaint concerned dangerously unhealthy prison conditions, not the lack of a salad bar.”

Decades later, it was as if Newman’s article had never appeared. In a 2015 brief before the Supreme Court, Michigan’s attorney general at the time, Bill Schuette, pulled out the peanut-butter anecdote again to argue that a prisoner’s case should be dismissed under the PLRA.

His brief used the word “frivolous” 48 times.