‘Trading too much and not investing enough’: Dmitry Balyasny on why he’s remade the hedge fund’s equities team

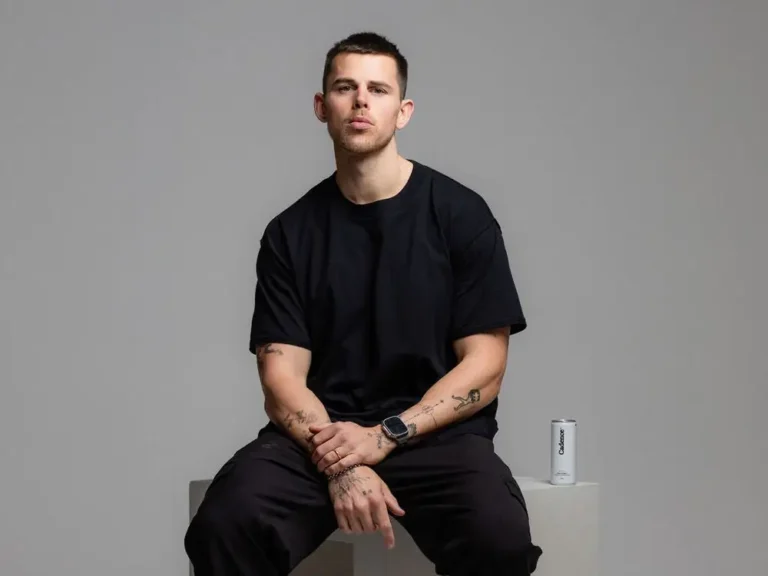

Dmitry Balyasny founded his hedge fund in 2001.

Throughout its 23-year history, Dmitry Balyasny’s firm has been known, first and foremost, as a stock picker.

While the $20 billion multistrategy firm has added strategies like macro, commodities, and quant over the years and expanded its head count to 2,000 people, the Chicago-based manager still leads with its equities expertise.

So when the firm’s equities teams were dragging the manager’s performance down to the bottom of the league tables in 2023, Balyasny decided to undergo a “course correction” in its largest business unit, the founder told B-17 in an interview at the firm’s office in London’s posh Mayfair neighborhood.

“People were trading too much and not investing enough,” Balyasny said.

The “top-down philosophical” refocus, he said, has been on ideas, research, and longer timelines. Instead of trying to “catch every wiggle” or make money on every market twitch, portfolio managers are being pushed to find multimonth or even multiquarter investment ideas, he said. The result has been lower position turnover and less trading in PMs’ books.

And performance rebounded in 2024: After a big November that had the manager up 11.6% through the first 11 months, the manager is set to land squarely in the middle of its peers for the year.

While the firm’s hiring — for the equities unit as well as other strategies — got most of the headlines for the manager this year, Balyasny said it was the improvement of existing stock-picking teams that drove the returns.

DNA change

Balyasny’s equities struggles coincided with multistrategy firms’ growth and hedge funds’ increased use of alternative data, such as credit-card transactions and email receipts, which can provide a sneak peek of a company’s performance before it reports earnings.

This data, which provided an invaluable edge a decade ago but is now table stakes at firms like Balyasny, pushed investors to focus “excessively on triangulating and calling quarters,” said Steve Schurr, a senior portfolio manager who was promoted to the equities leadership team in mid-2023, when the “course correction” began.

“It’s become a strategy of diminished expected returns” as more firms use this type of data, he told B-17.

Schurr, who started his career in investing working for the legendary short-seller Jim Chanos, performed well during the equities division’s run of underperformance. Balyasny identified his focus on primary research as a winner and pushed him to spread it across the firm.

“We had to change the DNA of how we conducted research here,” Schurr said.

The firm built out an internal research database called Telescope, which has an AI overlay to summarize things like podcasts, expert network calls, and sell-side research. A new 15-person internal research team with data scientists and former journalists has done 120 projects for PMs this year.

Schurr said he believed that “durable edge” for all multistrategy firms investing in equities would come through primary research, not alternative data.

“I think we are back to the anarchy of having to be good investors,” he said of the multistrategy sector, adding that “80% of a portfolio manager’s opportunity is going to be from equity selection.”

Player-coaches

As the industry has matured, the titans of the field have gone from brash traders to business-building executives. The leaders at Citadel, Millennium, Jain Global, Brevan Howard, and more do not run a book.

Steve Cohen, the billionaire founder of Point72 and owner of the New York Mets, stopped trading this summer — and it felt like the official end of an era.

But Balyasny has begun trading a book again for his firm after giving it up for a time. Other leaders on the equities team — including Schurr and Peter Goodwin, who’s launching an internal stock-picking unit called Longaeva Partners and plans to hire PMs to work underneath him — are also managing portfolios of their own.

Balyasny, who has tapped people to run his quant, commodities, and macro units, isn’t planning to hire someone to oversee equities. Jeff Runnfeldt, now the chief investment officer of Fortress’ multimanager platform, oversaw the equities unit, but Balyasny stepped into the role on an interim basis after Runnfeldt and the firm parted ways in October 2023.

For now, the interim tag has been removed. Balyasny said he believes that trading alongside his employees helps him connect with potential recruits as he’s in the trenches with them.

Balyasny has had its ups and downs — specifically in 2018 when the manager laid off 20% of its staff and saw investors redeem $4 billion. The circumstances this time around are much different, he said, thanks to the diversification of the firm’s assets and LP base.

In 2018, 90% of the risk was in equities; now it’s 40% to 50%. The firm’s investors were only 20% institutional in 2018; now that figure is 70%, giving the firm long-term capital partners.

Peter Goodwin’s new equities fund Longaeva — which is a type of tree considered one of Earth’s oldest and longest-living species — won’t begin trading until early 2025

That’s important to have as the firm has remade its biggest unit. There are 65 to 70 portfolio managers in the firm’s three equities groups — Balyasny, Corbets, and Longaeva — and plans to expand, specifically in Goodwin’s unit.

Schurr said the pitch to recruits was simple: “You’re not just going to be a cog in the machine.”

For years the best portfolio managers have had to choose between having all the resources and building a business — but Balyasny says you can have it all. He compares running an equities team to being a young company pitching a venture firm.

Year-end meetings between PMs and business heads lay out why someone should get certain resources and capital based on their plans and expectations for the year ahead.

While top investors can also launch their own funds, Balyasny argued that this path “is not really worthwhile” given where the capital in the industry is flowing — and which funds have been seeding new launches. “Why not be in-house and get all the resources?” he said.

Schurr has three questions for each potential PM: What’s your unique strategy? How do you build a team and a research process to support it? And how would you construct a portfolio to optimize it?

“Among the multistrats, I think we have a really compelling offering,” Schurr said, adding: “I’ll let others try to call quarters. I want Balyasny to be the house of the best investors.”

‘You have to grow’

Growth is, in many ways, a requirement of a multistrategy firm instead of a goal. Assets, head count, strategies, office locations — all should be ticking up if things are going as planned.

Balyasny said the firm is always looking for people “to deepen the bench” on both the investing side and the business side of the equation, such as Kevin Byrne, who was brought over from Millennium this year to be the firm’s chief operating officer. He pointed out that Byrne joined Millennium when that firm was roughly the same size — $20 billion, give or take — as Balyasny is now.

When asked if tripling the firm’s assets was the goal — which would put the manager close to where Millennium currently sits — Balyasny said he didn’t have a specific AUM goal in mind. Still, as long as the liquidity in the markets they trade in grows, their strategies should be able to as well, he said.

The firm wants to be a leading industry player, Balyasny said. “You can’t be substantially smaller than others,” he added.

Size certainly matters in the recruiting battleground as guaranteed payouts grow. Balyasny said the money the firm spent on new hires this year is in line with what the manager has historically invested in talent.

He said the manager had traditionally spent 1% to 1.5% of its AUM on recruiting annually, which would put this year’s figure at $200 million to $300 million. A significant portion of recruiting costs are tied to performance over time, he said.

This year, more of that recruiting spend has gone toward equities hires, including big names like Goodwin, who have commanded larger packages.

The firm knows that to keep up, “you have to grow over time,” he said. “But it doesn’t have to be a straight line.”