See inside a WWII-era U-boat, the only submarine that the US Navy captured intact and towed home

The German submarine U-505, captured by the US Navy during World War II, is on permanent display at the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

Submarine warfare played a pivotal role in the Battle of the Atlantic as German U-boats targeted merchant ships and troop carriers from the US and other Allied nations.

The underwater predators sank Allied ships faster than they could be replaced, starving the British of crucial war material, but the Allies eventually turned the tide as they implemented improved radar and sonar detection, codebreaking measures, and warship convoys.

In 1944, a US Navy task group hunted a Nazi U-boat in a top-secret operation that was only made public after the war ended, marking the first time the service captured an enemy vessel since 1812.

The U-505

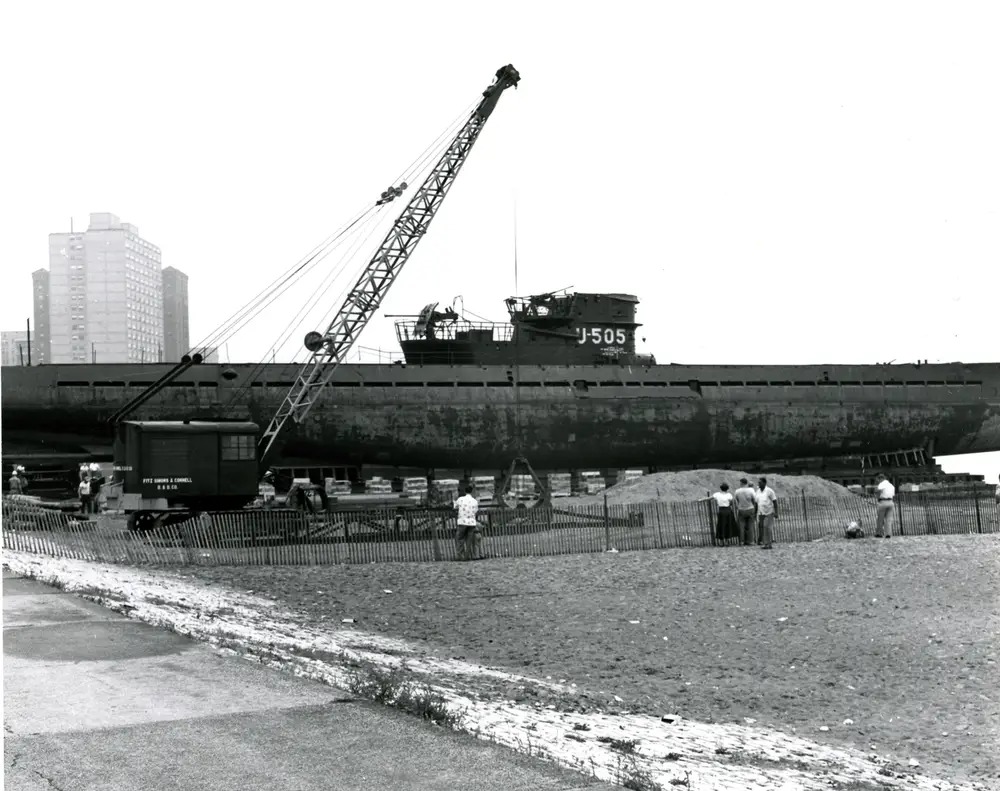

The submarine is held aloft near the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry as it is lowered into its future exhibit space.

Constructed at the docks of Hamburg, Germany, the U-505 was one of the German navy’s Type IX-class submarines, a long-range attack boat developed with longer dive times and agility compared to its predecessors.

Given the Kriegsmarine’s limited surface fleet, the U-boat was tasked with destroying shipping vessels in the Atlantic owned by the US and other Allied nations. After the U-505 entered the Battle of the Atlantic in 1942, it sank eight ships over a dozen war patrols and was credited with the loss of nearly 50,000 tons of Allied supplies and goods.

Tens of thousands died in the brutal war at sea. Allied mariners died in the torpedo explosions or drowned in the cold ocean waters afterward. In some incidents, U-boats also attacked passenger liners like the SS Athenia.

The string of sunken ships earned the U-505 a feared reputation as an underwater predator, but little did the crew know that its winning streak would someday come to an end.

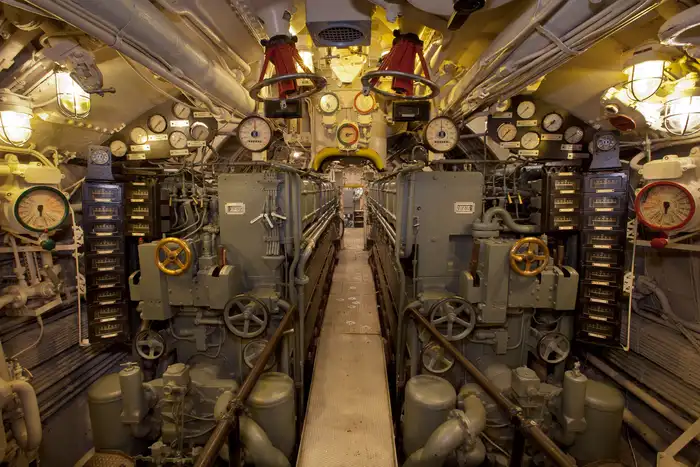

Inside the U-boat

The engine room of the submarine.

The U-505 had a displacement of over 1,100 tons and measured about 250 feet long. Propelled by two saltwater-cooled diesel engines, the U-boat had a range of nearly 17,000 miles, allowing it to deploy on long-range patrols to target merchant vessels.

Its surface speed was 18 knots, but its underwater speed was eight knots, which left it vulnerable to faster enemy ships while it operated below the surface. It mostly sailed on the surface at night and dove when spotted or when sneaking up on ships to torpedo.

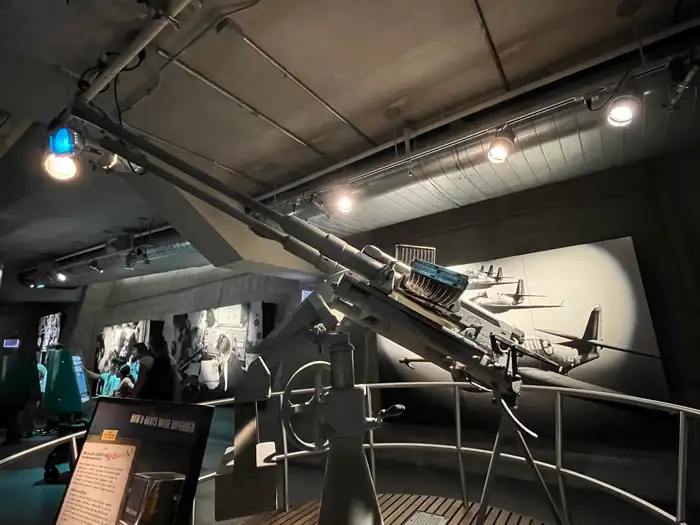

An underwater ship-killer

A display shows the antiaircraft naval gun that was equipped on the U-505.

Serving as an attack submarine, the U-505 had six 21-inch torpedo tubes — four in the bow and two in the stern — with storage to carry up to 22 torpedos at a time.

The U-boat’s surface armament included two antiaircraft guns and a 4.1-inch deck gun that could fire 15 rounds per minute.

Life aboard the German submarine

A torpedo sits nearby hanging cots in the submarine’s torpedo room.

Built to endure longer voyages and dive times, the U-505 could operate on patrols for 100 days or more. Despite the larger design of the Type-IX subs, the pressure hull was no bigger than a subway car.

As many as 60 people would live and work on the U-boat, taking turns sharing the 35 bunks, some of which were installed in the sub’s front and rear torpedo rooms.

Harsh living conditions

The submarine’s galley.

Space was hard to come by in the cramped hull. Only one sailor could stand in the tiny kitchen at a time. The fumes would waft from the engine room to the rest of the U-boat, leaving the crew’s limited provisions tasting like diesel.

Personnel often just wore shoes and underwear while living in the submarine, where temperatures could exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit during the warmer months.

The U-505 only had two bathrooms aboard — one of which was used to store food — but the crew never bathed and had to clean themselves with alcohol throughout the two-month patrols.

Tracking down the elusive boat

A view up the hatch.

On June 4, 1944, a US Navy hunter-killer group detected the U-505 operating off the coast of Rio de Oro in Africa’s Western Sahara. Commanded by US Navy Capt. Daniel V. Gallery, Task Group 22.3 was comprised of the escort carrier USS Guadalcanal and five destroyers.

Depth charges launched by the Edsall-class destroyer escort USS Chatelain, which detected the German vessel with sonar, jammed the U-boat’s rudder and flooded the aft compartment, forcing the vessel to surface.

Setting out on an anti-submarine sweep with the stated purpose of capturing and bringing back to the United States a German submarine, all units of the Task Group worked incessantly throughout the cruise to prepare themselves for the accomplishment of this exceedingly difficult purpose.

Salvaging the U-505

Water flooded in through a sea strainer that was left open by fleeing German submariners, threatening to sink the vessel.

German intelligence was vital during WWII, making recovery efforts for the sinking U-boat a top priority for the Navy task group.

German Capt. Harald Lange, who commanded the U-505, ordered the crew to abandon ship. To avoid capture, the Germans attempted to sink the U-boat with time bombs throughout the submarine and opened a sea strainer that caused water to rush inside the hull.

US Navy sailors who boarded the quickly flooding vessel disabled the scuttle charges and replaced the strainer cover.

In an operation wrought with numerous risks and dangers, the capture only resulted in one recorded casualty from the U-505’s crew as a result of Allied gunfire.

Captured intact

US Navy sailors stand atop the German submarine to secure a tow line to the bow.

A boarding party from the Edsall-class destroyer escort USS Pillsbury took a whaleboat to rescue the surviving 58 German sailors and salvage the U-505.

“Undeterred by the apparent sinking condition of the U-boat, the danger of explosions of demolition and scuttling charges, and the probability of enemy gunfire, the small boarding party plunged through the conning tower hatch, did everything in its power to keep the submarine afloat and removed valuable papers and documents,” Adm. Royal E. Ingersoll, then-Commander in Chief of the US Atlantic Fleet, said in the presidential unit citation awarded to the task group.

Towing it back to the US

US Navy fleet ocean tug USS Abnaki tows the captured submarine in the Atlantic Ocean.

Following the harrowing capture came the task of towing it back home. Operating under utmost secrecy, the US Navy painted the U-boat black and renamed it USS Nemo to hide its capture from the Germans.

The partially submerged vessel was towed over 2,500 nautical miles to Bermuda to study the submarine’s technology and intelligence on board.

The 58 sailors from the U-505 were transported and held at a prisoner-of-war camp in Louisiana, kept under special conditions like isolation and limited communication to keep the submarine’s capture a secret.

They remained at the camp until the end of the war, with the last of the captives repatriating back to Germany in 1947.

Uncovering German secrets

Detection and radio equipment on board the German submarine U-505.

The Navy recovered codebooks, thousands of communication documents, and two Enigma machines used by the German military to decode and encrypt messages to and from the U-505. Breaking Enigma codes allowed fleet commands to know where U-boats would attack. That, along with increasing Allied aircraft patrols for submarines, turned the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic.

American naval engineers uncovered that the Germans were developing an advanced acoustic-homing torpedo to target a ship’s propellers.

The intelligence also allowed the US to get more precise locations for German U-boat operations, redirecting merchant vessels from those areas.

“The Task Group’s brilliant achievement in disabling, capturing, and towing to a United States base a modern enemy man-of-war taken in combat on the high seas is a feat unprecedented in individual and group bravery, execution, and accomplishment in the Naval History of the United States,” Ingersoll said in the presidential citation.

Preserving the U-boat

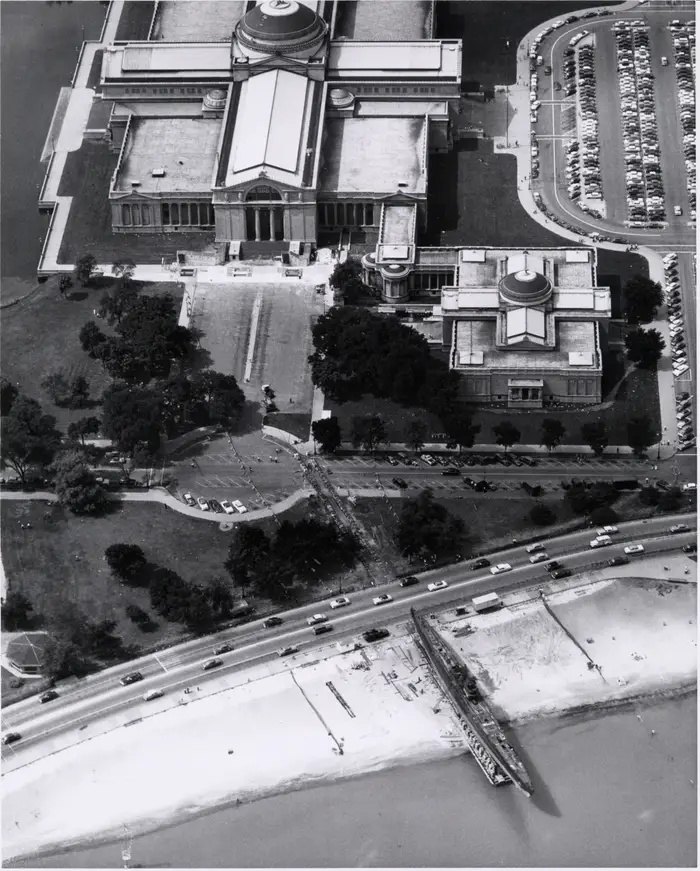

People enjoy a day at the beach near the captured German submarine.

Once the Navy learned what it could from the German submarine, the U-505 was destined to become gunnery and torpedo target practice, a typical fate for captured enemy vessels.

Two years after its capture, Chicago native John Gallery, the brother of Guadalcanal Capt. Gallery, contacted the president of the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry to preserve the wartime relic as an exhibit.

The Navy donated the U-boat to the museum, but the city of Chicago was tasked with raising $250,000 to move, install, and restore the submarine for exhibition.

‘Submarine crossing’

An aerial view of the U-505 on the beach as workers move the vessel toward the museum.

In 1954, the U-505 was towed from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where it was being stored, through 28 locks and four Great Lakes to Chicago.

After being towed 3,000 miles to 57th Street Beach in Chicago, the next hurdle was transporting the submarine from the waters of Lake Michigan to the museum — an 800-foot journey that included passing over an urban expressway.

Over the course of a week, engineers removed parts of the sub to make it easier to pull, then moved it across Lake Shore Drive using a network of rails and rollers to its permanent display outside the museum.

The U-505’s lair

The U-505 takes up a majority of the large exhibit.

The U-505 was initially berthed outdoors but was later moved into an indoor climate-controlled environment to better preserve it in the long term.

“The lives and the history that is embedded within the U-505, we don’t want to lose any of that,” Voula Saridakis, a curator at the Museum of Science and Industry, told B-7. “It’s so important, historically, of what this war was all about, especially the Battle of the Atlantic, which often, I think, gets overlooked in many ways.”

Due to its size, the exhibit’s concrete housing was erected around the U-505, surrounded by external exhibits that relayed the history of the submarine and the Battle of the Atlantic, whose toll included over 100,000 sailors and mariners and 3,500 merchant ships; Germany alone lost 783 U-boats and an estimated 30,000 crewmen.

The interior of the submarine was meticulously restored to replicate the atmosphere and environment as it was before its capture more than eight decades ago, complete with simulated lighting and sound effects to add to the immersiveness.

“As our visitors come through, they can get an idea of what life was like for these submariners and the living conditions and the tech and the innovation that went into this Type IXC,” Saridakis said.

In 1982, members from the US Navy’s Task Group 22.3 reunited with members of the German submarine’s crew in Chicago, marking the first time the German sailors saw the U-boat since the war.

“Part of what we want to do is preserve the history of the U-505, the battle, and the capture for future generations,” Saridakis said, “and we do this through telling this story, helping our guests understand its history and keeping this up and preserved for as long as we can.”