How companies are helping employees stuck between work and caring for aging parents

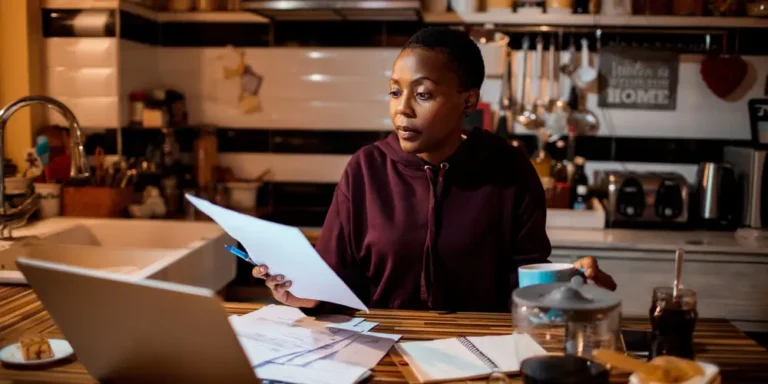

Last year, Ellen Kessler was visiting her mother in Florida when things went wrong.

“She called me at 3 a.m. and was just hysterical, frightened that someone was in the house,” said Kessler, who was staying at a nearby hotel. “When I got there, it was as if she wasn’t the same person. “I had no idea what to do.”

Concerned about leaving her then-91-year-old mother alone, Kessler decided to bring her back to Maryland with her, which she described as “the worst mistake I ever made.” Being away from home exacerbated her mother’s anxiety and added a demanding burden to Kessler’s daily life as a senior director at hotel chain Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc.

Kessler’s bind is becoming more common. According to US government data, more than half of the US labor force has caregiving responsibilities outside of work, and 37 million Americans can spend nearly four hours a day caring for an elder. According to AARP, workers who care for aging parents while also raising children at home, known as the “sandwich generation,” experience even greater emotional and financial strain.

Estimates of the economic cost of caregiving in the United States range from $264 billion to $600 billion. “The impact is felt by a surprisingly large share of the population, and it comes at an enormous cost,” according to a report by health insurer Blue Cross Blue Shield. Many people are forced to miss work, take leave, or quit their jobs in order to balance their professional and personal lives.

One startup is experimenting with new ways to assist working caregivers in carrying the load. When Kessler told her boss about her situation, she discovered that Hilton had a new elder-care benefit managed by a startup called Wellthy. Other major corporations, such as electronics retailer Best Buy Co., tech behemoth Meta Platforms Inc., and mutual-fund behemoth Vanguard Group Inc., provide Wellthy’s services to their employees.

According to Gallagher Surveys, only 12% of companies provide some form of elder-care assistance. Though an increasing number of large employers provide paid caregiver leave and many provide referral or counseling services, few provide tailored, expert advice on navigating the complex, acute challenges of caring for elderly family members. As a result, Wellthy faces little direct competition.

This relative scarcity of elder-care options contrasts with the increased availability of child-care benefits such as pretax set-asides for daycare expenses and emergency backup-care services.

Wellthy assists workers in navigating the plethora of issues that can arise when an elderly family member requires care. When Kessler contacted Wellthy, she was connected with care consultant Lynda Cooke. Kessler’s mother has macular degeneration, which impairs her vision, but she refused to move to a facility with full-time caregivers, so Cooke assisted the family in finding a home health aide.

Then, after a nighttime fall that resulted in a broken rib, Kessler’s mother reconsidered assisted living. “She said, ‘Ellen, I will not fight you anymore,'” Kessler recalled. Cooke was able to redirect the conversation and provide Ellen with detailed questions to ask the facilities, fee negotiation advice, and emotional support.

“Between the hospital, rehab and trying to work, it’s a lot,” Kessler told me. “You really feel the wear and tear of being there for your parent.”

Employee assistance programs (EAP) offered by many large corporations typically cannot assist employees in navigating the labyrinthine maze of long-term care providers, regulations, and payment options. Some employers provide referral services to vendors, but a shortage of home health aides and other workers in low-paying, high-turnover health-care roles can make getting help difficult.

“It’s a big, gaping hole,” said Boston Consulting Group managing director and partner Suchi Sastri, who was part of a team whose research estimated that the nation’s caregiver shortage, combined with its aging population, will cost the United States $290 billion per year beginning in 2030. “I don’t think it’s top of mind right now, but it has to be on the agenda of CEOs.”

Lindsay Jurist-Rosner co-founded Wellthy in 2014 after struggling to balance a demanding marketing career with caring for her mother, who suffered from multiple sclerosis and died in 2017. She began by providing the concierge service to individuals, but quickly shifted her focus to selling it to employers as a sponsored benefit, which means it is free for employees. Companies typically pay between $3 and $6 per month per employee. This gives them access to Wellthy’s network of care specialists, many of whom are experienced social workers and are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“People come to us in times of crisis,” Jurist-Rosner explained. “You have few moments in your life like this, so we have to deliver extraordinarily well.”

Last August, Christopher Cowan, the chief human resources officer at ChristianaCare, a Delaware-based health-care network with 13,700 employees, gave Wellthy a chance. While Cowan admits that “it’s not cheap,” he believes it will pay for itself if it allows him to retain 11 nurses or three executives who would otherwise leave due to caregiving responsibilities.

Caregiving obligations, according to Harvard Business School professor Joseph Fuller, who has studied the effect of caregiving on the labor force and advised Jurist-Rosner when she launched Wellthy, are a primary driver of employee turnover. “It does not take much utilization to justify the coverage,” he went on to say. In addition to elder care, Wellthy offers assistance to young children, teenagers, and employees.

Hilton’s human-resources chief, Laura Fuentes, said Wellthy saved the company’s 49,000 U.S. employees 20,000 hours in less than a year, persuading her to expand it to the company’s UK and Ireland employees. Wellthy has saved Best Buy’s 90,000 employees about 60,000 hours over the last two years, according to Kamy Scarlett, senior executive vice president of human resources, corporate affairs, and Canada, and has one of the highest satisfaction ratings of any of its employee benefits.

“I went through this years ago and if I had Wellthy then, I would have made different decisions,” she said.

Despite everything Wellthy does — its specialists will also interview vendors on workers’ behalf — it cannot offset the costs of care, which can be unpredictable and steep. Wellthy is also unable to diagnose illnesses or prescribe medications.

Balancing work and family can be difficult for employees who do not have access to elder-care benefits, particularly those who still have children living with them. Kelly Mann, 50, works in a high-level corporate position advising companies on hybrid work. She has a teen daughter with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and aging parents who are suffering from serious health problems.

Her 79-year-old mother was recently admitted to the hospital with diverticulitis, and a subsequent MRI revealed a brain bleed, necessitating a neurological consultation. Her mother’s health-insurance provider initially denied her mother’s rehab stay, forcing Mann to spend five hours on the phone appealing the decision. Her mother then had a stroke, landing her back in the hospital.

Her father, 85, was diagnosed with midstage dementia around the same time and required a daytime home health aide. Mann’s husband, who works in residential real estate, assists, but Mann admits that juggling everything is difficult.

“I have an unlimited amount of time off,” Mann explained. “If you do not, you are screwed.”