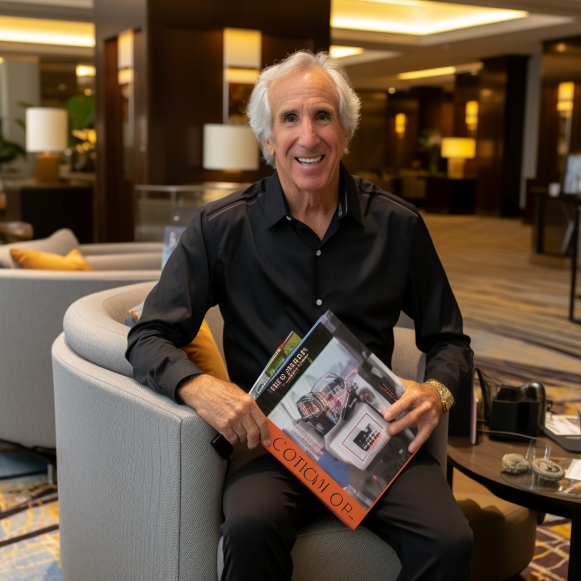

Could anyone wear his fame more comfortably than Henry Winkler?

CHICAGO (AP) — Henry Winkler’s smile is the smile of an old friend seeing you for the first time in years, or a genuine affectionate smile for an unexpected new friend, or a smile that nudges into a laugh. It’s a smile so genuine and warm that you despise yourself for wondering how any human can generate such emotion a dozen times a day for 50 years of public life.

And yet, at 8 a.m. in suburban Rosemont, there was that smile again.

You can see it in a hotel Starbucks, where Winkler commands a small crowd despite the late hour; they stare in awe, as if a 12-point buck had just wandered in. You see it over breakfast in a hotel restaurant, which means a sip of coffee, a taste of food, then a stranger approaching cautiously to ask for a picture, telling him he was their entire childhood, over and over. You notice it at the hostess counter, waiting for a table.

A long, slender man in jogging clothes turned offhandedly, noticed Winkler, did a double take, interrupted what Winkler was saying, and exclaimed:

“Henry!”

“Oh! Kiefer! Hello!” Winkler responded to Kiefer Sutherland, who was in town for a few days as well, doing one of those fan convention autograph marathon gauntlets. They spoke briefly, and Sutherland apologized for “Ground Control,” a 1998 film in which Sutherland and Winkler played minor roles — there’s a reason you’ve never heard of it.

Winkler dismissed the apology, and they agreed to meet up soon. “‘Ground Control,'” Winkler later told me, “was the worst movie ever made by a human being.” But look who’s there: Kiefer Sutherland! A lovely performer. That makes me so happy!”

Winkler is aware of the impact he has on others, but he wholeheartedly reserves the right to gush over others all the time. In his new memoir, “Being Henry: The Fonz… and Beyond,” he writes about meeting Joaquin Phoenix at the Screen Actors Guild Awards, saying, “I can’t believe I’m meeting you,” to which Phoenix replied, “You can’t believe you’re meeting me?” “How are you?” he asked the hostess. There are a lot of obstetricians in the hotel today.”

“Opticians,” she corrected herself. “But so nice to see you.”

“I’m Henry,” he introduced himself.

“Well, yes… “I understand,” she admitted. “Having a good time in Chicago?”

“Unbelievable time,” he said, a big smile on his face.

The waiter at our table asked Winkler if he wanted coffee. Winkler inquired as to the man’s origins. Bangladesh, said the man. “Nice!” Winkler explained.

“Far away,” said the man.

“And then there’s the flooding,” Winkler added.

“Right now, yes.”

“Your family is fine?”

“My family is here!”

“Oh, well — good!”

That goes on and on all day. Winkler’s voice has a melodious New York City working-class lack of arrogance, and it flows without many staccato thoughts or half-completed sentences, and it almost never ends with a negative thought. Years ago, he told himself that he would never let a negative thought enter his mind. “Remove it any way you can,” he said to me. “‘I don’t have time for you,’ ‘I don’t want you in my life,’ and that changes your whole countenance, then you get to be here, having breakfast, this morning, right now.”

In fact, though I would never write this about a celebrity, if you see Winkler in public — and he will be in Chicago this week for the release of his book and a sold-out appearance at the Chicago Humanities Festival — introduce yourself. He really enjoys meeting new people. He told me over breakfast that he had just met Christie Brinkley’s agent, “who was at William Morris when I started.” At the hotel’s medical convention, I met a woman. And a woman who began law school at the age of 50. I met a doctor whose 9-year-old dyslexic daughter. “It was only at Starbucks.”

“Oh my God!” exclaimed a woman as she approached our table.

“I’m Henry,” he introduced himself.

“And I am shaking,” she added. “All these opticians … does Henry Winkler need glasses?”

“I do!”

“Good to meet you!” I’ll see what I can come up with!”

Fame hasn’t always been like this, but it’s been like this a lot since the mid-1970s. In his memoir, he describes a publicity event in Dallas for “Happy Days,” the television series that made him as culturally ubiquitous in the 1970s as disco and “Star Wars.” He was there with his co-stars, Ron Howard, Donny Most, and Anson Williams, when their limo was blocked by a crowd of 20,000 people. He had vowed never to summon the tough-guy cool of his character, Fonzie, but here, as Fonzie, he yelled: “You are going to part like the Red Sea!” The crowd then parted, much like how Fonzie controlled electronics with the bump of a fist — until one teen, watching Winkler closely, exclaimed, “He’s so short!”

Winkler turned around and said, “(Expletive) you, I’m not short.”

Henry Winkler is attractive, but he is not made of wood. “I went with instinct,” he explained. Everyone, including Ron, was terrified. It can become claustrophobic. But because I’m dyslexic, I rely on instinct.”

When anyone younger than Generation X recognizes him, it’s because he was in Adam Sandler movies; he was murdered in the first “Scream” film; he played Dr. Lu Saperstein on “Parks and Recreation” (he delivered most of the cast’s fictional babies); he played administrator Sy Mittleman on the cult comedy “Children’s Hospital”; and he played Barry Zuckerkorn, the worst lawyer alive on “Arrested Development.” And, of course, for portraying a desperate, failed acting coach on HBO’s “Barry,” a role that earned him an Emmy in 2018 after a string of acting nominations over the years.

Indeed, those are the two extremes of his creative life: “Happy Days” on one end and “Barry” on the other, separated by 45 years, a slew of forgettable TV movies, and the agony of typecasting. He started playing Fonzie in his mid-20s and left the role in his mid-30s. He is now 77 years old. He claims that when “Happy Days” was canceled, he had no backup plan.

He’d been afraid for decades that he’d been typecast beyond employment. He became a strange kind of cultural royalty, indelible and endearing but with a small, sparse body of work. That can be difficult for an actor who graduated from Yale University’s School of Drama. Some actors fade into their roles. It took Winkler a long time to realize that the Fonz lurks behind whoever he plays. He embodied the Fonz so completely that a statue of him, the Bronze Fonz, stands in downtown Milwaukee; it’s not a statue of Winkler, but it is. There’s a lot that’s bad about that, but there’s also a lot that’s good these days. The Fonz became a layer to Winkler’s roles over the last decade, there but not the only thing there. He recalls a smidgeon of himself — and the recognition that an audience is aware of him.

“It took me until now to do the TV I’m doing,” he went on to say. “I couldn’t have done something like ‘Barry’ at the time.” To be perfectly honest, I was not authentic. I knew who I thought I should be, but I’m only now at peace with myself. And it’s so frustrating that it’s taken me 40 years to figure it out. ‘I wish I knew then,’ ‘I wasted time.’ It was wonderful back then, but because I am neurotic, the best times were marred by anxiety about who I wasn’t yet.”

In the late 1970s, at the height of his fame, he turned down the role of Danny Zuko in the film adaptation of “Grease.” He did not want to be stereotyped as a greaser. He said today, “I would just see it as work and do it.” But it hurts. He declined the part and went home to drink ginger ale, he explained. “John Travolta went home and bought a 747.”

The woman who had inquired about eyeglasses came back to our table. She had set down her coffee, forgotten about it, and the cup had become cold. “Well, now you don’t have to blow,” Winkler explained.

“Haven’t heard that in a while,” the woman winked.

“Now did you think that would come out of that woman?” Winkler slapped the table, laughed, and turned to face me. Make people feel at ease, and you’ll learn so much about them!”

He asks strangers where they’re from and what they did before doing what they’re doing now. When asked about acting, he is friendly but quick and grimly serious. Any hint of irritation is softened with verbal word balloons like “Yowie!” and “Holy moly!” And when strangers approach him, their faces soften and they stare, because, though the term “iconic” is overused, Winkler is so iconic that if you were a kid in the 1970s, he was a plastic doll, a T-shirt, a magazine cover, a board game, and a lunch box.

The irony is that the man is more interesting, a paradox of determination and timidity.

His parents were Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, and they were tyrannical toward him, as his book makes clear, and he was not a fan of either of them. He has since co-authored over three dozen children’s books with Lin Oliver, the majority of which have strong empowerment themes, including the popular Hank Zipzer stories about a dyslexic child. But, until recently, he regarded himself as second-rate. In 1973, as a young actor in Hollywood, he worked out of a friend’s office to use the phone and scrounge for acting jobs, sometimes pretending to be speaking with agents to avoid looking like a failure. Despite this, he was auditioning for Fonzie less than a month after moving to Los Angeles.

“Work defined me,” he explained. “I didn’t have enough self-control to wait and calm down.” I was nobody, nothing, and I only grew half an inch with each new job.”

Despite being a young actor with a big break, he had enough self-esteem to insist on Fonzie showing vulnerability, and even sadness, before accepting the role. In an early Christmas episode, Fonzie’s surrogate family, the Cunninghams, catch him in a lie: he insists he has family to spend the holiday with, but they find him home alone, cooking for one. But, as the character grew into a monolith, ennui gave way to near-paranormal control of jukeboxes and, most infamously, the ability to jump sharks. Even his catchphrase, “Ayyyyyy,” was more of a reaction to Jimmie Walker and “Good Times,” which made “DY-NO-MITE” a tough competitor for “Happy Days.”

His family cashed in with quickie paperbacks as his star rose. Yale, who was initially dismissive of his sitcom work, asked for money. Being Fonzie, most painfully, meant becoming an albatross to coworkers who lived in the shadow of his wingspan. Any “Happy Days”-related memoir will tell you the same thing: They adored Henry but despised the emphasis on Fonzie. ABC wanted to rename the show “Fonzie’s Happy Days,” and for Christmas, the network gave the entire cast wallets — except for Winkler, who received the latest home technology, a VCR. “I found out from Ron how he felt,” Winkler explained. “I remember thinking to myself how stupid I was. What insensitivity! It was ultimately beneficial to him because that treatment inspired him to become a director. And changing the name! People would suffer. An acting ensemble like that must maintain cohesion at all costs.”

Decades later, Winkler is so tuned in to the ups and downs of fame and acting that, as he writes in his book, he has a small speech ready to capitalize on his name if he loses everything: “I could roll up to somebody’s house and say, ‘Hi, it’s Henry Winkler, I know this is crazy, but do you have leftovers?’… “I literally planned that scenario.”

When our meal was finished, we stood up, and Christopher Lloyd approached and hugged Winker. Then came the great character actor Danny Trejo. This isn’t as random as it sounds when you’re Henry Winkler. Everyone wanted to take pictures with him. Then there’s a mother and son. Then a stranger passed by and exclaimed, “I love your outfit!” “I love color!” said Winkler, who was dressed in lime green pants and a bright plaid sports jacket.

The more he did this, greeting friends and strangers in a never-ending receiving line, the more I assumed he was trained in improv. He experimented. But not what Second City does, he said. He once got on stage with “Parks and Recreation” co-star Ben Schwartz for an improv night and said, “I was so far over my head.” We were on separate continents. He’s brilliant, and I was curious about how to blend into the wall.”

Another paradox: two of his best acting performances were improvised. He sneaks pastries into his briefcase in his first “Arrested Development” episode. In his best film, “Night Shift,” directed by Ron Howard and co-starring Michael Keaton, Winkler runs out of money and begins writing checks to an insistent subway saxophone player. Those were both unscripted segments.

Winkler performs best in the heat of the moment.

I found him in front of his table at the autograph convention the next morning, at least 40 minutes before his scheduled time. Every other famous name sat behind their tables, receiving fans during set hours — Susan Sarandon across from him, Peter “RoboCop” Weller beside him. Winkler took a step forward and approached each fan in turn. His line was never the longest, but it was the most consistent, and his smile was unmistakable.