A basic income program funded by descendants of slave owners provides $1,000 a month as a form of reparations

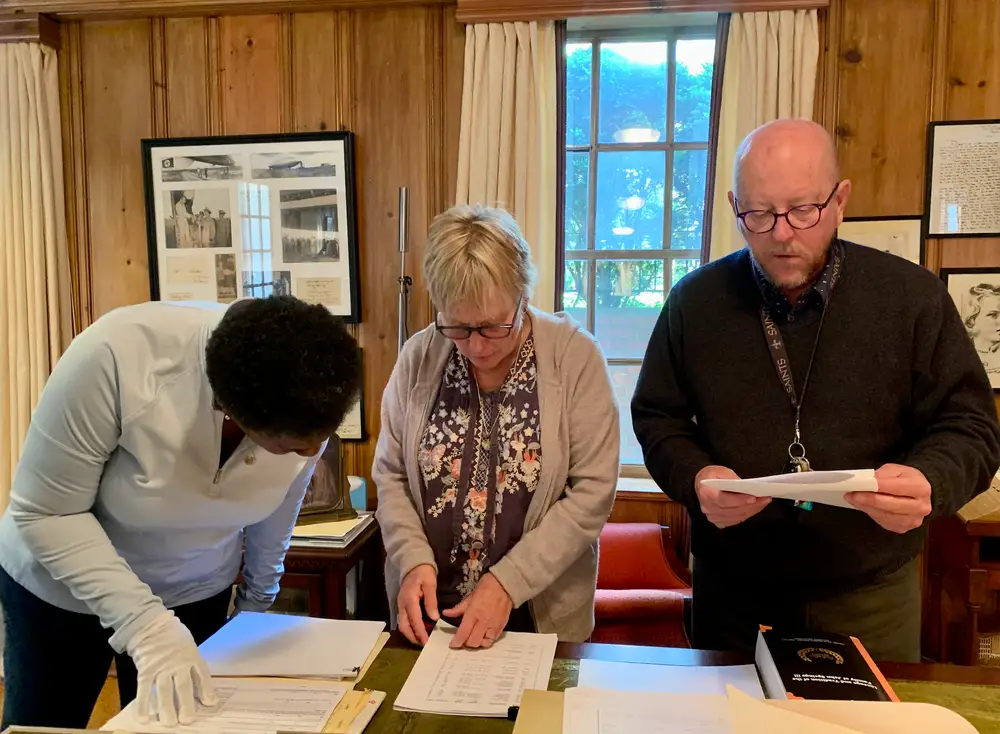

Buck and Gracie Close examine their family’s records with genealogist Core Lyles at the White Homestead in Fort Mill, South Carolina.

Buck and Gracie Close aren’t shy about their family history.

The siblings, both in their 70s, are the descendants of slave owners who operated lucrative cotton mills in North Carolina. One of their ancestors was a prominent slave trader in the region.

“We were raised with the myth of the Old South and how wonderful everybody was, and kind, and family-like with the slaves that they did hold,” Gracie Close, a 72-year-old based in Washington state, told B-17.

“The role of slavery in creating generational wealth was not something that we discussed or thought about growing up,” said Buck Close, who is 74 and now resides in Louisiana. “We were always immersed in the valor of the Old South. At that time we were, anyways.”

The two siblings are now privately funding a yearlong basic income program in Louisiana focused on transferring wealth to people who were victims of racist policing, an act they view as a form of reparations.

The Truth and Reconciliation Project was brought to life by the American Civil Liberties Union of Louisiana, which selected 12 people who were “survivors of police misconduct who did not receive restitution in the courts,” the ACLU of Louisiana website says. Program recipients told the ACLU they had spent thousands of dollars on court and legal fees while trying to fight charges and clear their names.

Since November 2023, each recipient has received $1,000 a month in no-strings-attached payments. They also get access to free financial coaching, mental health counseling, and legal expungement services. The monthly checks will conclude this month, but the services will continue being offered for at least another year.

“Those services were very important,” Gracie said. “I think it puts a foundation under them that they’ve never had access to before.”

In a progress report after the program’s sixth month, recipients of the guaranteed monthly income said they had better access to healthier food and basic necessities (such as transportation, housing, and healthcare). They were also significantly more comfortable withstanding surprise expenses.

“I am proud of the GMI program we funded at the ACLU and look forward to the culmination of it in December. We will get to spend a day with the recipients and hear how they feel it has worked for them,” Gracie said.

An artist used his $500 monthly basic income to build his hip hop career: ‘It’s not feasible to create art in a place of distress.’

Texas lawsuits keep challenging guaranteed basic income programs, calling no-strings-attached cash ‘unconstitutional’

Unraveling generations of hard truths

In 2019, Buck, a donor to the ACLU of Louisiana, met for coffee with Maggy Baccinelli, a senior director. They stayed in touch and continued their conversations in the following years.

“She started talking about the roots of your generational wealth. She brought the subject up, and that was the spark, really, for me,” Buck said. “I was very acquainted with racism and the evils of that. But I never focused on the history of my own family.”

Buck and Gracie grew up on the property of the White Homestead in Fort Mills, which is the site of the last full meeting of the Confederate Cabinet in 1865, according to the family’s archives and The Rock Hill Herald, a local newspaper.

While it wasn’t a secret to Buck and Gracie that their generational wealth had been earned using slave labor centuries prior, it also wasn’t something that they felt they had taken accountability for as a family.

“I don’t think my mother and father hid anything from us. I think this was just the milieu of the South at that time. Nobody was questioning the methods by which ancestors had become prosperous,” Buck said.

At the ACLU of Louisiana, Baccinelli and her colleagues started “discussing what it would be like to go deeper into the family history and to study the arc of slavery to mass incarceration and overlay the family history onto that arc,” Baccinelli told B-17.

“We presented to Buck our idea about it, and he agreed, and he said that he wanted to invite his sister, Gracie, to participate,” she said.

With funding from Buck, the ACLU hired a genealogist to research the Close family history, including records of people their ancestors had purchased and enslaved.

“It is time to spread the wealth and admit responsibility for our ancestors’ participation in slavery,” said Gracie, who noted she acts out of responsibility rather than guilt. “To work for justice today, we have to consider our past.”

In November, the two siblings published an op-ed urging other descendants of slave owners to take similar action to investigate their pasts.

Basic income as a form of reparations

When considering how to address past wrongs, Buck and Gracie “latched on” to the idea of a guaranteed basic income.

Small-scale guaranteed basic income programs have sprouted around the country in recent years, inspired in part by the success of pandemic-era cash handouts. These basic income programs offer unrestricted cash payments to specific groups of vulnerable low-income residents for a limited time period. The programs differ from a universal basic income, which would offer regular cash payments to all residents regardless of their financial status.

“Our goal is to try to transfer wealth gained by us through the enslavement of others to descendants of the enslaved,” Buck said. “So it fit that marker pretty well.”

American police systems can trace their roots back to slave patrols, Baccinelli said.

“The reason why it’s reparations is because policing started in the 1600s as slave patrols,” Baccinelli said. “That’s the beginning of the arc to where we are now, and so we see racist and unconstitutional policing as a vestige of slavery. I would venture to bet that every person in the program is a descendant of somebody who was enslaved, but I don’t have confirmation on that.”

To that end, Buck and Gracie hope to establish a similar basic income fund in South Carolina, the site of their ancestral home, that “transfers wealth from us as descendants of enslavers to other people who were descendants of the enslaved.”

“We’re optimistic,” Buck said.