A new COVID booster is here. Will those at greatest risk get it?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends new COVID-19 booster vaccines for everyone, but many people who need them the most will not get them. Around 75% of Americans appear to have skipped last year’s bivalent booster, and nothing indicates that uptake will be better this time around.

“Urging people to get boosters has really only worked for Democrats, college graduates, and people making over $90,000 a year,” said Yale University epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves. “Those are the same people who will get this boost because we’re not doing anything different to address the existing inequities.”

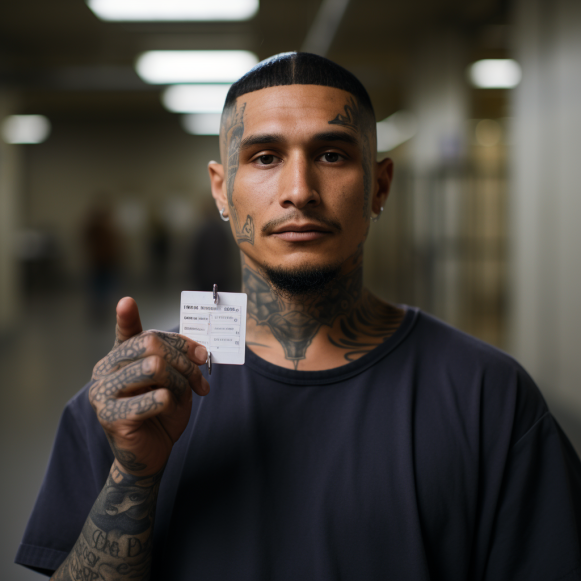

Boosters have been shown to strongly protect people against severe COVID and death, and more modestly prevent infection, as the effects of vaccines offered in 2021 have waned over time. They can have a significant impact on those who are most likely to die from COVID, such as the elderly and the immunocompromised. Re-vaccination is also important, according to public health experts, for those living in group housing, such as prisons and nursing homes, where the virus can spread quickly between people in close quarters. A boost in protection is also required to compensate for the persistent disparities in COVID tolls between racial and ethnic groups.

However, mandates and the urgency of the moment have largely ended the intensive outreach efforts that successfully led to adequate vaccination rates in 2021. Data now suggest that those receiving booster doses are often not those most at risk, implying that the COVID toll in the United States may not be significantly reduced by this round of vaccines. COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths have increased in recent weeks, and the disease remains a leading cause of death, with approximately 7,300 people dying from the disease in the last three months.

Tyler Winkelman, a health services researcher at Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, believes 2021-style outreach is required again. Thousands of people were hired back then to tailor communication and education to different communities, as well as to administer vaccines in churches, homeless encampments, and stadiums. “We can still save lives if we are thoughtful about how we roll out the vaccines.”

To make matters worse, this is the first round of COVID vaccines that are not fully covered by the federal government. Private and public health insurers will provide them at no cost to members, but the situation for some 25 million-30 million uninsured adults — primarily low-income and people of color — is in flux. On September 14, the CDC announced the start of plans to temporarily provide vaccines to the uninsured, funded in part by $1.1 billion in pandemic emergency funds through the Bridge Access Program.

Costs are most likely an issue, according to Peter Maybarduk of the Washington-based advocacy organization Public Citizen. Moderna and Pfizer have more than quadrupled the price of the vaccines to around $130 per dose, up from around $20 for the first vaccines and $30 for the last boosters, increasing overall health-care costs. Maybarduk noted that the US government funded research involved in the development of mRNA vaccines, and that the government passed up an opportunity to request price caps in exchange for that investment. Vaccine sales generated billions of dollars for both companies in 2021 and 2022. Pfizer expects $14 billion in COVID vaccine sales this year, according to Moderna’s most recent investor report. Maybarduk claims that if the government didn’t spend so much money on boosters like Medicare, Medicaid, and its access program, it would have more money for equity initiatives. “What decisions would be made to expand the response if these vaccines had remained at the same price?”

People aged 75 and up have accounted for more than half of all pandemic deaths in the United States. However, while the initial vaccines were quickly adopted in nursing homes, boosters have been less popular, with less than 55% of residents in Arizona, Florida, Nevada, and Texas receiving the bivalent booster released last year. Rates are as low as 10% in some facilities across the country.

Some of the largest outbreaks in the United States have occurred in jails and prisons, but booster uptake appears to be low. According to Minnesota EHR Consortium analyses of electronic health records, only 8% of incarcerated people in jails and 11% in prisons received the booster last year. Approximately 38% of people in California prisons are up to date on boosters. Boosters are effective. A study of California prisons discovered that the first two doses were only about 20% effective against infection, compared to 40% for three doses. (Prison staff benefited more from three doses, with a 72% effectiveness, presumably because the risk of infection is lower when not living in the facilities.)

Low-income groups are also at a higher risk, due to factors such as a lack of paid sick leave and medical care. According to Tiana Moore, policy director at the University of California-San Francisco’s Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative, roughly 60% of homeless people in California reported chronic health conditions in surveys. According to studies, members of this community age faster, with people in their 50s experiencing strokes, falls, and urinary incontinence at rates comparable to those in their late 70s and early 80s.

Booster rates among people without housing are largely unknown, but Moore is concerned, claiming that they face significant barriers to vaccination because many lack medical providers, knowledge of where to go for vaccines, and transportation. “Many of our participants expressed concern about leaving their belongings unsheltered because they don’t have a door to lock,” she explained. “This emphasizes the importance of meeting people where they are in an effective booster campaign.”

Throughout the pandemic, black and Hispanic people have had higher hospitalization and death rates than white people. Furthermore, these groups are significantly less likely than white patients to be treated with the COVID drug Paxlovid. (Hispanics can be of any race or race combination.)

People choose not to be vaccinated for a variety of reasons. Those who live further away from vaccine sites have lower rates of uptake on average. Misinformation spread by politicians may account for political disparities, with 41% of Democrats receiving a bivalent booster compared to 11% of Republicans. Lower vaccine coverage among Black communities has been linked to medical system discrimination, as well as poor health care access. However, when given information and easy access to vaccines, many Black people who were initially hesitant got them, implying that it could happen again.

However, Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, stated that the decline in reporting on vaccination and COVID rates makes tailoring outreach more difficult.

“If we had the data, we could pivot quickly,” he said, adding that this was previously possible but that reporting lapsed after the public health emergency ended this spring. “We’ve gone back to the old ways, re-creating the conditions that allow inequities to exist.”