A new tool shows what the climate crisis could feel like in your city

A heat wave in Bengaluru, India earlier this year caused a dire water shortage that forced residents to ration their use.

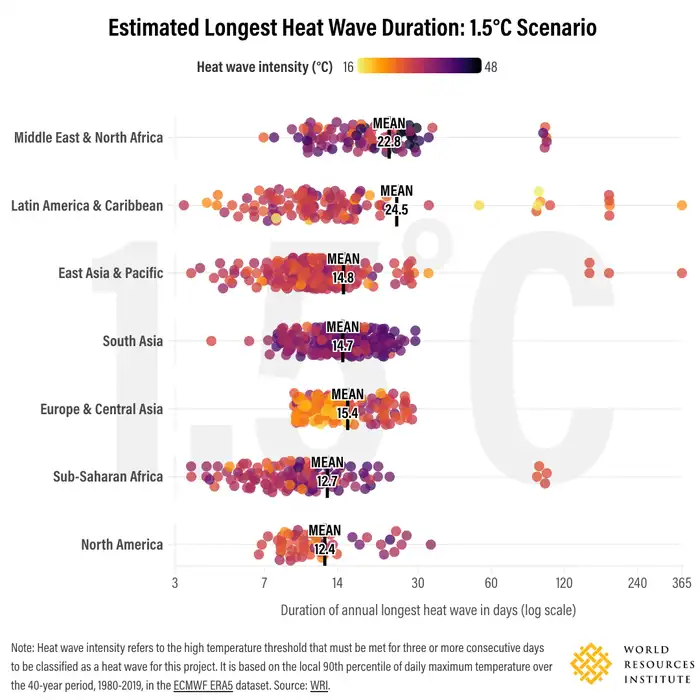

Monthlong heat waves. Skyrocketing energy demand. Greater risks of mosquito-borne diseases.

These are the climate hazards that people living in nearly 1,000 of the world’s largest cities will continue to face as global average temperatures rise through the end of the century, a new analysis by the World Resources Institute, an environmental-research group, found. And the impacts won’t be felt equally. People living in low-income cities in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Indonesia face the greatest threats.

The findings come as 2024 is on track to be the hottest year on record, and billions of people are expected to move into urban areas in the coming decades. More than half the world’s population, or 4.4 billion people, lives in cities. By 2050, city dwellers are forecast to make up two-thirds of humanity, with the vast majority of that growth in Africa and Asia. Some 2 billion people currently live in the cities that WRI studied, from Seattle and Rio de Janeiro to Johannesburg and Bengaluru, India.

“Most climate modeling looks at hazards, exposure, and risks at a national scale because that’s where a lot of policymaking and international agreements are focused,” Eric Mackres, the senior manager of data and tools at the WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities and a coauthor of the study, said. “But that’s disconnected from where people live. We wanted to put more localized information in the hands of those decision-makers so they’re informed about the risks that they are likely to experience.”

Local climate hazards

To make predictions at a city level, Mackres said WRI built on global climate modeling done by hundreds of other researchers. These models contain daily information — both historical data and projections through 2100 — on air temperature, humidity, and precipitation. WRI used that data to make its own projections about the length and frequency of heat waves, how often people will need to cool their homes and workplaces, and the number of days with optimal temperatures for mosquitoes in cities with at least half a million people. WRI compared how those local hazards are expected to change as global average temperatures rise from 1.5 degrees Celsius to 3 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels — a threshold scientists say the world is likely to cross by 2100.

The world has warmed by about 1.2 degrees so far compared with mid-1800s levels, and the consequences are playing out around the world.

In Bengaluru, India’s fifth-most-populous city, extreme heat has caused severe water shortages and surging energy demand. Under 1.5 degrees of warming, heat waves could last about 13 days on average and stretch to nearly 38 days as global temperatures rise, WRI found. Bengaluru last year launched its first climate-action plan, which includes planting trees and expanding green spaces to help cool down urban centers.

An enormous outbreak of dengue fever is underway in Brazil. In Rio de Janeiro, peak days for transmission of mosquito-borne illnesses could increase from 69 to 118 a year, WRI found. The city is investing in vaccines, and community health workers are hunting down places that help mosquitoes breed, including standing water, to reduce risks.

Meanwhile, places that haven’t had to consider cooling strategies are now being forced to, including the US Pacific Northwest. Seattle was once the least-air-conditioned city. Now it ranks second behind San Francisco after a series of deadly heat waves prompted residents to install AC. The trend is playing out in cities that are already hot, too, like Tehran, Iran, and Marrakech, Morocco, and spiking energy demand along the way. If that demand is met with fossil fuels like oil, gas, and coal, it could exacerbate the climate crisis, WRI said.

WRI noted that there are limitations to its research, in part because there are a lot of unknowns about the future. National governments and cities can slow the climate crisis and protect people from its impacts, including by shifting away from fossil fuels and investing in infrastructure that’s more resilient to heat and storms.

“Our findings are not a foregone conclusion,” Mackres said. “These are choices we have between 1.5 and 3 degrees of warming, and none are out of the realm of possibility. It’s really important that national decision-makers understand the impacts on cities and the actions that cities can take to both reduce climate change and to adapt to what’s coming.”