After my mom died, I thought I’d never enjoy the holidays again. It took me years to find joy in my grief.

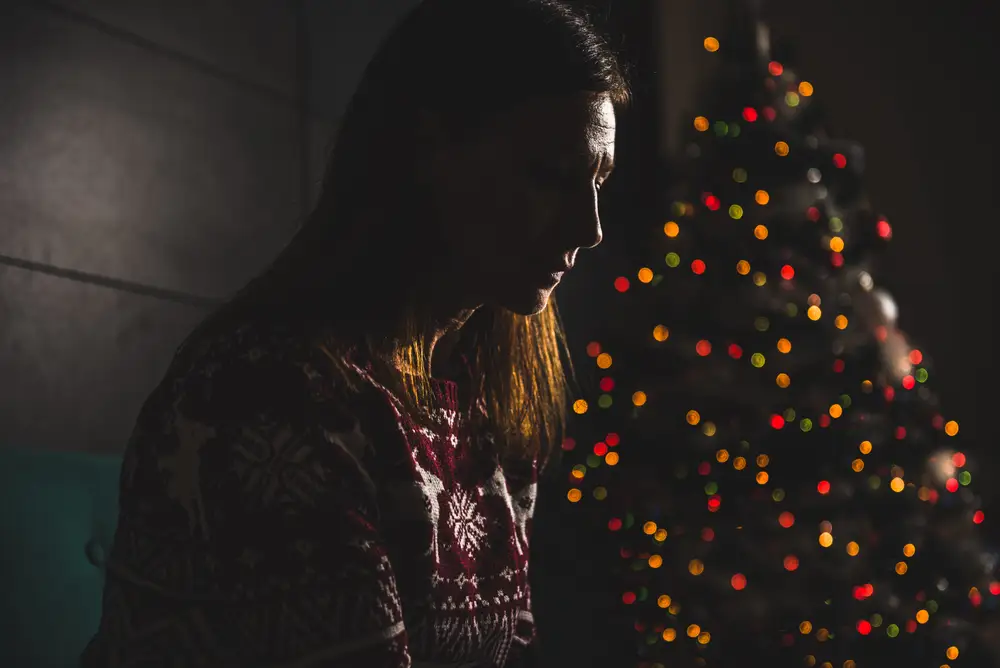

The author (not pictured) didn’t feel like celebrating the holidays after the death of her mom.

My mother had a penchant for making things special.

She knew how to grab joy where she could. She decorated our home for every holiday, donning earrings and sweaters that matched the occasion.

On Christmas, she’d watch with joy while we opened her thoughtful gifts and ate our favorite holiday dishes. I don’t remember a lot about the first Christmas without her in 2018. But for the next few years, like The Grinch, I wanted Christmas gone. If I’d had energy that wasn’t solely dedicated to staying upright amidst my grief, I might have even taken down a Christmas tree or two in the night.

Nothing could compare to what my mom did

At 20-years-old, I didn’t know how to make things special myself. I wasn’t really interested in trying, either, or welcoming anyone else’s efforts.

Nothing could compare to the holiday scene she’d set. No one else could make the food, decorate the house, or wrap the presents right.

I couldn’t accept this truth: that everything would change. So I put a wall up between Christmas and I, white-knuckling my way through December. I didn’t want to watch holiday movies or listen to holiday music. I wanted to dismiss it as any other insignificant day.

I’d get together with my family and try to pretend I was happy to be there, but I felt guilty for pretending and resentful of having to. Yet I didn’t think not pretending was an option.

The thing about grief, though, is that with each year, the tide rose, washed away more grit, and left me softer.

I had to find beauty in things again

From the spring of 2019 through the spring of 2020, I spent a year living in Denver. I needed to change my surroundings — and make a change that was in my control — to teach my brain that there could be beauty in newness. I needed to learn what the newness would make of me.

When I returned to Michigan at the start of the pandemic, I returned as someone who had made new memories in a new place. It helped me accept that things could look different and still be good. The holidays could still be special if I wanted them to be.

During the Christmas of 2020, my sister and her family had COVID-19, so I stood outside their window in the snow for 15 minutes before going back to my apartment alone. I noticed, with sad poignancy, how much I wanted to be inside with her, my brother-in-law, my nephews, and my dad.

In 2021, I met my now wife, and I had the delicious instinct to make things special together. To create our own traditions. She prioritizes fun, and it rubbed off on me. I came to love taking part in her family’s traditions, too. It became clear that there was so much celebration to go around, no matter what it looked like.

I look forward to the holidays now

This year will be the seventh Christmas without my mother, and I look forward to the holiday now.

My wife and I put up our tree on November 3rd. To me, Christmas symbolizes coziness, a focus on joy, an excuse for good food and extra sugar and sitting around a table with people I love.

While there are traditions, new and old, that I cherish, it’s less about the specifics and more about the feeling. And, grief is a part of that feeling. It’s just not such a sharp ache anymore — more like a familiar smell that reminds me of a warm and nostalgic childhood memory.

Holiday grief (and any grief, for that matter) isn’t a thing to be conquered and moved on from, but a thing to accept and learn how to live alongside. In those early years, much of my strife came from wishing I could prevent change and control my feelings. When I don’t set rigid expectations of myself, and instead let the tide wash over and soften me, that softness allows space for grief and joy.

I’ve learned how to appreciate specialness any way it comes and grab joy where I can — even if it means putting the Christmas tree up before Thanksgiving.