CEO of failed supersonic plane startup on what went wrong — and how other companies might find success

Supersonic startup Exosonic closed its doors on Friday following low customer interest and difficulty raising funds.

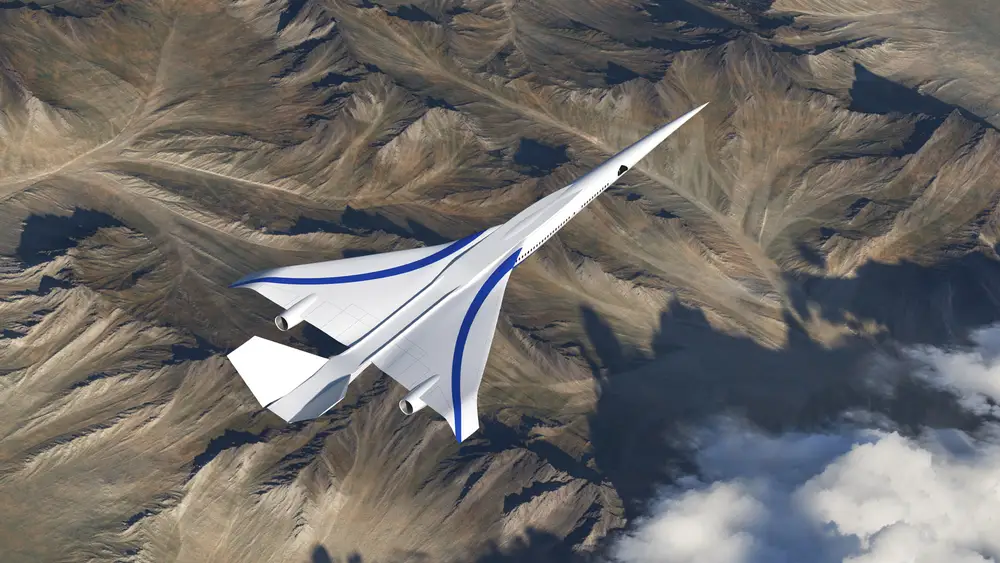

A handful of startups are vying to revive supersonic flight, but one contender just dropped out of the race.

Exosonic, which had been working for five years to build faster-than-sound jets for commercial and military use, announced its shutdown on Friday, citing a lack of continued funding and low customer interest.

The company had two main projects: a quiet passenger plane capable of Mach 1.8 speed and an uncrewed supersonic aircraft for fighter jet target practice. It had backing from private equity investors, a contract from the US Air Force, and a flying sub-scale prototype.

In an interview with B-17, Exosonic CEO Norris Tie said the company hoped its Mach-speed airliner would drastically cut travel time between faraway nations.

Crucial to the company’s promise was work to eliminate the sonic boom that prevents supersonic planes from flying over land — an issue that severely handicapped the legendary Concorde when it pioneered supersonic passenger travel in 1976.

“The goal was that by the time we were ready to hammer out the commercial design, all the regulatory framework for the boom would have more or less been established,” Tie said. “Then we could go back to designing the airliner after what we hypothesized would have been a successful UAS (uncrewed aircraft systems) business at that point.”

Exosonic CEO Norris Tie (Right).

Since 2020, the company had raised about $4 million in funding, according to PitchBook estimates. Its closure leaves fewer players working to achieve the faster-than-sound dream.

“As history shows, in many areas with new technology, there are often many more players initially than the market can support,” University of Illinois aerospace engineering professor Michael Bragg told B-17. “It was inevitable that there would be a downselect of supersonic aircraft makers. Let’s hope someone is successful before they are all gone.”

A new Mach-speed passenger jet would be too expensive and time-intensive

Supersonic travel was already achieved nearly decades ago with the Concorde, which could cross the Atlantic in as little as three hours and operated commercially for about 30 years.

But it was extremely costly and ended in disaster, stoking concerns that largely convinced the industry to end flights.

“Some investors said the timeline for a supersonic commercial aviation product was too long and capital intensive,” he said, adding passenger Mach flight was the company’s main focus for the first two years.

Tie said with full capital, meaning billions more dollars, it could take 10-15 years to build, certify, and deliver a new supersonic plane. And that’s if the supply chain, potential design setbacks, and other factors don’t add abnormal expenses.

Tie also said engine manufacturers aren’t investing in supersonic flight — hindering one of the industry’s most vital components: power.

A rendering of the Boom Overture supersonic airliner.

Boom Supersonic, another faster-than-sound startup, has been forced to build its own engine after failing to make a deal with major engine manufacturers, who remain focused on conventional jet engines. The company has been in business for about a decade and has developed a sub-scale prototype.

“Boom has said it would cost up to $8 billion to build its supersonic plane, and that’s a low number,” Tie said. “The company has only publicly funded less than $1 billion. It’s a long road, and I don’t know how it’s going to get done.”

Boom has announced billions of dollars worth of orders from American Airlines and United Airlines for its supersonic Overture jet, which is planned to fly as soon as 2029.

American has agreed to purchase up to 20 with options for another 40, while United has ordered 15 with options for 35 more.

The US Air Force changed its mind about Exosonic’s training drones

Investors pushed Exosonic to focus on military contracts instead of a commercial airliner, Tie said. This was the smallest product the company could develop while still generating some revenue — until the Air Force changed its mind.

“They didn’t want fighter jet drones focused on training; they wanted one focused on combat, which has been a priority for the past two or three years,” he said. “That’s what took away all of the funding that we were going after, and we couldn’t recover.”

A rendering of Exosonic’s Revenant supersonic military drones.

He said commercial air combat companies’ interest in Exosonic hinged on the USAF. Once the Air Force’s interest faded, so did the interest of any potential commercial players, like Drakken International, who could have used the uncrewed drones for training or other military needs.

Without a defense arm of the business, Tie said the commercial side didn’t have a chance.

Tie said hypersonic travel is a more likely commercial option

Tie said part of the problem with getting supersonic funding is because it isn’t a shiny new concept. Humans have been doing it since the 1940s, and there isn’t any “terribly new technology to develop there.”

He said a better approach for Exosonic would have been to focus on hypersonic travel.

Rendering of Venus Aerospace’s Mach 9 “Stargazer” passenger jet.

A handful of hypersonic startups, including Venus Aerospace, Hermeus, Destinus, and Spectre Aerospace, plan to build ultrafast jetliners. Venus is testing its high-Mach-speed advanced propulsion system and has achieved supersonic flight with a drone using a rocket engine.

Tie believes SpaceX’s Starship could be one of the likeliest contenders. Elon Musk’s project is set to transport satellites and astronauts to space but could also shoot into orbit and back to connect nearly any two cities in an hour or less.

“Hypersonic is certainly in vogue, and so that makes sense to go in that direction,” he said. “Supersonic is unfortunately not in vogue.”