China and Russia are in a bad marriage that the West shouldn’t try to break up

China and Russia’s partnership is littered with potential issues that limit its potency and staying power.

During the darkest days of the Cold War, in the 1950s, the West worried that the Soviet Union and China had joined forces to form a massive Communist bloc.

But those fears proved overblown, as Beijing and Moscow soon went from allies to bitter enemies that clashed over their long border. Fast forward to today, and growing military ties have again raised the specter of a Sino-Russian alliance that unites two of the most powerful nations in the world.

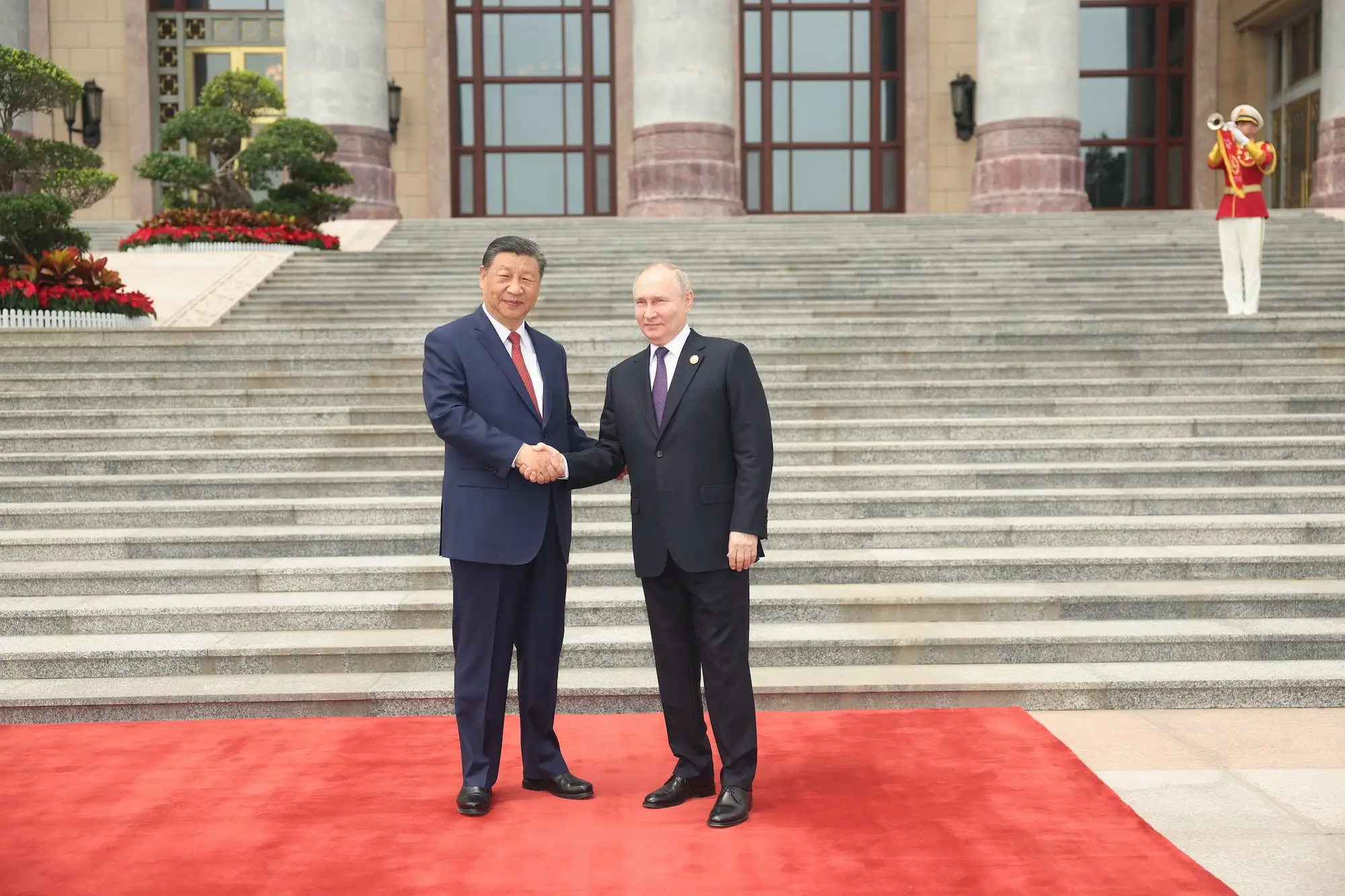

But this partnership is not a solid alliance like NATO that’s built on mutual defense and interoperability of its forces. “The Sino-Russian relationship is probably best characterized as a marriage of two imperfect partners who share a deeply cynical view of the U.S.-led international order but often hold divergent visions of the order that they believe should replace it,” according to a report on Sino-Russian cooperation by the RAND Corp. think tank.

“These two imperfect partners realize some level of shared, albeit unequal, dependency while simultaneously harboring deep suspicions about whether they can trust or rely on the other,” the study said.

This may be scant comfort to Western leaders who fear a scenario where Russian aggression in Europe is simultaneous with a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, which would overstretch US resources and allow America’s allies to be overwhelmed.

Already, Russia’s military and China’s People’s Liberation Army have held around 25 joint exercises since 2005, involving ships, aircraft and ground troops. Beijing and Moscow have teamed up to fly joint patrols, including a 2023 incident where they flew near South Korean airspace.

Equally important is that China has become a key enabler of Russia’s war in Ukraine. With Western sanctions depriving Russia of key components such as electronics, China and its vast manufacturing base have emerged as a major supplier of microelectronics, drone parts, and other components.

But these don’t equate to the sort of integrated operations practiced by the US and Britain in World War II, where American troops served under British commanders and vice versa, or by NATO today.

“Policymakers and planners should avoid overestimating the state of military cooperation and operational integration that exists between Russia and China,” RAND warned.

China sent only a few thousand troops to Russia’s massive 2018 war game of an estimated 300,000 participants.

Exercises involving Russian and Chinese forces have been “described as more ‘parallel’ than ‘joint,’ meaning that Russia’s military and the PLA are given set tasks and timelines, perform them in synchronized yet independent fashion, and overall have limited interaction in such areas as planning and C2 [command and control],” RAND said. “For this reason, these exercises have in reality done relatively little to promote interoperability at either the operational or the tactical level.”

The result is military cooperation that is more symbolic than practical. “China’s commitment to the exercises is relatively low,” RAND said. “The PLA [People’s Liberation Army] sent around 3,200 soldiers to Russia’s 300,000-strong Vostok 2018 exercise and just 1,600 to Russia’s Tsentr-2019 exercise (in which the Russian side fielded almost 130,000 soldiers). It appears that the PLA is more interested in learning from Russia than in sharing insights into its own military capabilities or training as equal partners, whereas, for Russia, the goal is to present an image of joint cooperation with China to the West to counter an impression that Moscow is isolated and vulnerable.”