CRISPR gene editing could kill HIV. But is it a cure?

Gene-cutting technique is targeting infectious disease, hoping to eradicate virus.

Three patients have received CRISPR gene-editing therapies in an attempt to eradicate HIV from their bodies, in a provocative first step toward an elusive end to a devastating disease that has claimed 40 million lives.

The results — whether the men were cured or not after the one-time intravenous infusions this year — have not yet been disclosed by the San Francisco biotech company that developed the technology based on UC Berkeley’s Jennifer Doudna’s Nobel Prize-winning research.

However, Excision BioTherapeutics reported this week at a meeting in Brussels that the potential treatment, called EBT-101, is safe and has caused no major side effects.

Six more men will be treated with higher doses, possibly at UC San Francisco. Participants in the research program take a risk by discontinuing their anti-HIV drugs for 12 weeks after gene-editing treatment to see if the virus has been eradicated.According to the company, the data will be presented at a medical conference next year.

“We are opening the door to how this new drug will work and what potential it has for people living with HIV,” said Dr. William Kennedy, Excision’s senior vice president of clinical development. “Ultimately, we see this as a fundamentally new approach.”

According to him, the novel strategy could potentially treat other chronic infections in which the virus hides latently, such as hepatitis and herpes. It preserves human DNA.

“We were super excited about this, and getting the chance to be among the first to do human studies of gene editing for a cure,” said Dr. Priscilla Hsue, professor of medicine and principal investigator for the study’s clinical trial site at UCSF. “If we can permanently remove viral DNA, the thought is, people would get this infusion and then be done.”

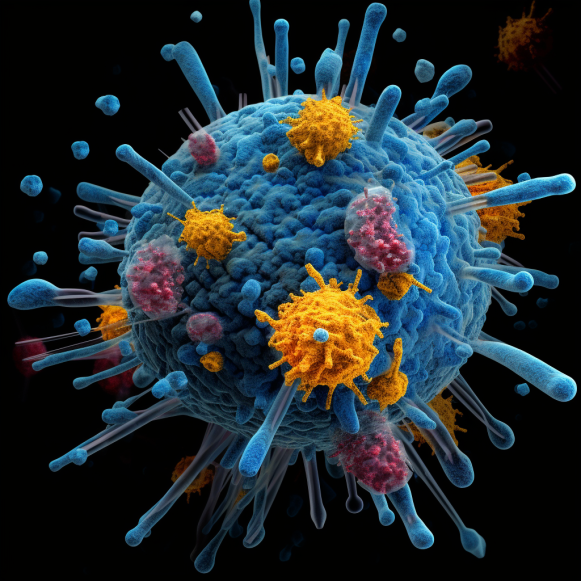

EBT-101 is designed to find specific viral sequences without cutting human DNA. An empty virus is used to deliver the “guide RNA” that marks where to cut in the CRISPR-based therapy. Cas9 is an enzyme that acts like a pair of scissors. The medicinal solution is administered intravenously.

It received the FDA’s “fast track” designation in July after animal experiments proved successful. SIV, a virus related to HIV, was safely and efficiently removed from the genomes of rhesus monkeys with a single injection. Previously, it removed HIV from nine of 23 mice.

However, there is a significant gap between promising mouse results and human success. Patients will be recruited at Quest Clinical Research in San Francisco, Washington University in St. Louis, and Cooper University in Camden, New Jersey, in addition to UCSF.

Treatment has evolved in the four decades since the AIDS virus was isolated. Strong antiretroviral drugs, when taken on a daily basis, can suppress the virus and control illness. Medicine can also be used to prevent infection.

However, a cure is required to bring the pandemic to an end. Nearly 39 million people worldwide are infected with HIV. Approximately 77% of them are being treated.

So far, only three cases of HIV cure have been documented. Two of the men received bone marrow transplants from donors who possessed a mutation that prevents HIV infection. The third case involved a woman who received an umbilical cord blood transplant. However, because all three treatments were aimed at cancer, this is not a viable option for the average HIV patient.

“The future of so many lives depends on another breakthrough,” said Mark S. King, an HIV/AIDS activist in Atlanta and author of the book My Fabulous Disease, who has lived with the virus for nearly 40 years.

“A lot of people think that this was all rectified when we got successful treatments,” he went on to say. “But the difference between a treatment and a cure, or a vaccine, is profound.”

Excision BioTherapeutics was founded on research from Kamel Khalili’s lab at Temple University in Philadelphia, where he is also the director of the Center for NeuroVirology and Gene Editing.

Its research is funded in part by the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine, which is funded by taxpayers. On Wednesday, preliminary findings from the study were presented at the European Society of Gene and Cell Therapy.

CRISPR gene editing, an ingenious system discovered by Jennifer Doudna, a biologist with UC-Berkeley’s Innovative Genomics Institute, can cure genetic disease by cutting out a piece of a person’s DNA with tiny molecular scissors. It is now used to treat a variety of diseases, including sickle cell anemia, nerve disease, and congenital blindness.

Scientists wondered if CRISPR could cure HIV by severing the virus’s DNA. Excision’s method cuts the virus in two places, removing genes required for replication.

“This is an exceptionally ambitious and important trial,” said Fyodor Urnov, a UC-Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and an IGI gene editor, in an email. “It would be good to know sooner rather than later” whether it works, he said, “including, potentially, no effect.”

Earlier research in Khalili’s lab demonstrated that CRISPR could locate and destroy HIV genes in cells.

Long-term survivors like King welcomed the findings with caution. “Am I interested? Yes. Wary? Absolutely. We’ve been here many times before. We’ve heard of many promising developments over the years, only to have the rug pulled out from under us — due to the perplexing nature of how HIV operates in the body.”

HIV has been difficult to eradicate because it hides in our cells, according to Dr. Jyoti Gupta of the PACE Clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, which specializes in HIV care.

“The virus is very smart,” she explained. “It integrates into our immune cells’ host genomes, which are supposed to protect us from infection.” It simply lies there, hidden.”

“As soon as someone stops the therapy, the latent virus starts replicating again, within days,” Gupta said. “Then there’s virus everywhere.”

Excision patients will be monitored for 15 years, according to Kennedy.

Even if it just stops replication for a while, Gupta believes it will be beneficial. “In this case, less is more.” So it’s reasonable if a patient can come in for an infusion once a year, for example, and the virus won’t resurface for a year.”

Excision’s therapy, it is hoped, will become a permanent cure, freeing patients from daily pill-popping.

“Scientists tell me that this is going to be part of a cure someday,” said Matt Sharp, 68, a Berkeley-based AIDS activist who has lived with the virus for 38 years. “And I shrug my shoulders and say, ‘Here we go again.'”

“Now we just have to get the research done,” he went on to say. “We’ve got to have hope, because the epidemic isn’t over.”