Elon Musk hates OpenAI’s for-profit transformation plan. He’s not the only one.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman.

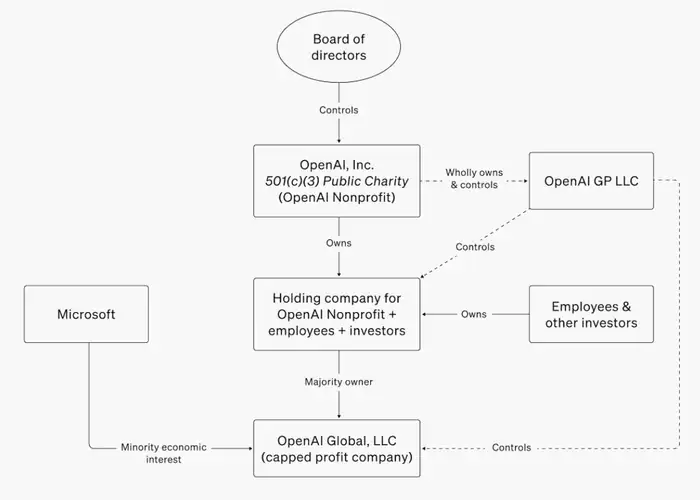

Sam Altman is attempting a thorny maneuver, transforming OpenAI from a subsidiary of a convoluted nonprofit into a more conventional business.

Jungwon Byun knows what that’s like.

In 2023, the organization Byun cofounded, an AI lab named Ought, went through a similar transition. Launched in 2018, Ought built AI research tools and was structured as a nonprofit because its cofounders didn’t expect AI to be commercially viable anytime soon, Byun said in an interview. Then ChatGPT launched, AI mania took hold, and the leadership team realized their structure might be a hindrance to raising capital and pursuing their mission.

The decision was made to spin out Ought’s core product, Elicit, as a for-profit company, along with most of its staff. Byun and several other executives set to lead the independent Elicit recused themselves from discussions, and a firm specializing in asset valuations was hired to independently appraise the value of Elicit so the remaining nonprofit, Ought, could be paid appropriately. (Byun declined to share the exact price, though she said Elicit chose to pay a premium on top of the recommended price.)

OpenAI’s planned transformation is on a far grander scale but faces similar questions and potentially more gnarly challenges.

Altman wants to extricate OpenAI’s revenue-generating business from its nonprofit parent, creating a more traditional company that can take in investments and give stock to shareholders who expect big returns.

The process is complicated by OpenAI’s complex corporate structure, the billions of dollars it has already raised from investors, and Elon Musk’s attempts to block the deal.

It’s not just Musk though. A growing chorus of critics, including entrepreneurs, other companies and charities, investors, academics, and activists, say OpenAI may be about to make a grave mistake.

Byun is one of them.

“Artificial general intelligence is the most transformative technology of our lifetime, and OpenAI is absolutely at the frontier and one of the most important players in that,” she told B-17. “So I think giving up governance rights to controlling the most important technology of our lifetime is an insanely huge decision and will affect all of humanity at a very great scale for a long time.”

Her advice to OpenAI’s charitable parent organization: Do not sell to anyone.

“I don’t know, obviously, the details of what pressures they’re under and what the details are of the options they’re considering and how it affects the mission,” Byun said. “But from what I can see, I absolutely would not sell those governance rights or give them up.” OpenAI didn’t respond to requests for comment over the past week.

A convoluted structure

A chart showing OpenAI’s structure.

OpenAI was established as a nonprofit in 2015. Over time, its need for capital to pay for AI development prompted it to establish a for-profit subsidiary to raise venture funding and pursue business partnerships and revenue-generating products. This and various other subsidiaries are controlled by the nonprofit, which is controlled by a board of directors chaired by Bret Taylor, alongside Altman, Fidji Simo, Larry Summers, and other business luminaries.

The board’s main legal obligation is to further the nonprofit’s charitable mission, which is to build “safe and beneficial artificial general intelligence for the benefit of humanity,” rather than delivering returns to shareholders.

OpenAI now seeks to transition to a more conventional corporate structure, turning the for-profit subsidiary into an independent public benefit company that controls “OpenAI’s operations and business.”

PBCs are relatively common. This approach takes into account the interests of shareholders, other stakeholders, and the public. OpenAI has said that with investors taken care of, this will help the startup raise “necessary capital with conventional terms like others in this space.”

Finding fair value

Elon Musk, an OpenAI cofounder turned bitter rival.

OpenAI said the remaining nonprofit would receive shares in the public benefit company “at a fair valuation determined by independent financial advisors.”

That may be the ultimate challenge — and one made more complex by potential conflicts of interest.

OpenAI investors and others focused on the startup’s business-focused future may prefer to pay the nonprofit less for its assets and control, leaving the new for-profit entity with more financial firepower. However, some of these people could be in positions to influence the valuation and decision-making.

Musk, an OpenAI cofounder who acrimoniously split from Altman, has sued the startup over its plans. Musk and a group of other investors also made a bid in February to acquire the nonprofit parent OpenAI Inc. for $97.4 billion. That was more than half of the total value of the entire startup based on its most recent funding round.

“It is in the public’s interest to ensure that OpenAI, Inc. is compensated at fair market value,” the Musk consortium said in a statement. “That value cannot be determined by insiders negotiating on both sides of the same table.”

Ellen Aprill, an expert on charities at the UCLA School of Law, said OpenAI’s board has an obligation to make sure the nonprofit is getting a fair value for giving up its assets and control.

“One of the very big issues is what is fair market value?” she told B-17. “In particular, how much should the nonprofit get for giving up control?

“Part of what Musk and his group were trying to do with this offer is to set at least some floor, some sense of what the fair market value would be,” she added. “Putting it out for auction — let’s see what people would pay.”

Should Altman recuse himself?

Altman.

Taylor, the OpenAI board chairman, officially rebuffed Musk. “OpenAI is not for sale, and the board has unanimously rejected Mr. Musk’s latest attempt to disrupt his competition,” Taylor wrote in a statement. “Any potential reorganization of OpenAI will strengthen our nonprofit and its mission to ensure AGI benefits all of humanity.”

Days earlier, Altman shot the bid down with a post on X that mocked the struggles of the Musk-owned social network: “no thank you but we will buy twitter for $9.74 billion if you want.”

Altman’s post prompted some discussion of whether he was, or should be, recused from this process.

“When it comes to looking at a conflicted transaction like this one, it’s much easier to satisfy the court’s review if you take people who are on both sides of their transaction out of the negotiations,” said Peter Molk, a law professor at the University of Florida.

However, he noted that under Delaware law, Altman isn’t legally required to remove himself. Molk also cautioned against recusing too early.

“There’s value in his being there. Along the way, he can provide useful insight and information that’s actually useful for OpenAI, for the nonprofit, if they’re going to go ahead with that process,” Molk said. “You want to try and strike a balance that allows them to do their job, that helps a transaction occur in a way that’s actually beneficial to all parties, but then have them take themselves out of the picture once you’re beyond that point.”

Meta and others pile on

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

The existing for-profit parts of OpenAI have already raised billions of dollars in pursuit of artificial general intelligence, or AGI, which the startup defines as systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work. This has raised hackles among some consumer advocates.

Public Citizen, a consumer watchdog, has repeatedly assailed the AI startup, accusing it of betraying its nonprofit mission. “The nonprofit board has behaved as a subordinate to the for-profit, and has done nothing that evidences any commitment to the nonprofit mission,” said Robert Weissman, the copresident of Public Citizen.

He argued that the solution is to forcibly dissolve the nonprofit and auction off its assets for the benefit of a new independent charity not linked to the current OpenAI board.

Meta, Facebook’s parent company, raised similar concerns, writing to California’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, in December to ask him to step in.

“Taking advantage of this non-profit status, OpenAI raised billions of dollars in capital from investors to further its purported mission,” the company wrote. “Now, OpenAI wants to change its status while retaining all of the benefits that enabled it to reach the point it has today. That is wrong. OpenAI should not be allowed to flout the law by taking and reappropriating assets it built as a charity and using them for potentially enormous private gains.”

In late January, a group of 25 charities, including one started by the eBay founder Pierre Omidyar and his wife, piled on. The coalition urged Bonta “to take prompt legal action to ensure that OpenAI’s assets are not illegally diverted for private gain.”

Dubious legal justifications

Rose Chan Loui, a law professor at UCLA specializing in nonprofit and philanthropy law, is skeptical of the legal justifications for OpenAI’s plan.

She said the proposed changes would amount to a change in purpose for OpenAI’s current nonprofit. To do that under Delaware law requires one of four criteria to be met:

- Is the charity’s original purpose now illegal to fulfill?

- Has the mission become impossible to fulfill?

- Is it now impracticable to fulfill?

- Or is it too wasteful to fulfill?

“We don’t think any of those apply here,” Chan Loui said. “We keep going back to — your purpose is not to be first in the race to AGI. Your purpose is to make sure that AGI is to protect, and ensure safe development of AGI.”

The lesson of other nonprofits

OpenAI’s existing structure — a nonprofit that controls a for-profit subsidiary — is unusual, but by no means unheard of.

The Mozilla Foundation, for example, owns a tech company, Mozilla Corporation, that produces the Firefox internet browser. “Nonprofit organizations can not only coexist with commercial enterprises but also challenge them to do better,” a Mozilla spokesperson said in a statement. “Nonprofit commitments provide the kind of public interest compass we don’t see enough of in tech.”

Another parallel comes from the healthcare sector. In the 1990s, in the face of mounting financial pressure, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association allowed its affiliated nonprofit plan organizations to transition to for-profit businesses. Many subsequently did so, to the chagrin of some.

“The mission of the nonprofit in most Blue Cross Blue Shield plans was to provide affordable, accessible healthcare to people,” a Consumers Union attorney told NPR in 2010. “And now the mission is to make money for stockholders.”

The most substantial threat to OpenAI’s plans though, might not be Musk or other critics. The California and Delaware attorneys general are both making inquiries into the specifics of the transition.

“The current beneficiaries of OpenAI have an interest in ensuring that charitable assets are not transferred to private interests without due consideration,” Delaware’s attorney general, Kathleen Jennings, said.

AGs have meaningful legal powers to get involved. In 2002, Pennsylvania’s attorney general intervened in a planned deal by the nonprofit foundation that controls the for-profit Hershey chocolate brand to sell its assets to Wrigley for $12 billion, citing the potential harm to the town of Hershey.

The sale was ultimately called off.