Fear the Fed? History says US stocks will underperform once interest rates fall, a consensus-defying researcher warns

Investors who think US stocks will charge higher may be in for a letdown.

Investors are waiting with bated breath for lower interest rates, but researcher Lyn Alden believes they should have sweaty palms instead.

Markets have been glued to commentary from the Federal Reserve, which will decide how much rate cuts are needed next month. The consensus view from strategists is that more moderate rates will keep the US economy afloat and, by extension, US stocks.

Neither of those conclusions holds much weight with Alden, who runs the eponymous research firm Lyn Alden Investment Strategy.

After all, it takes many months or even years to see the full impact of interest rate adjustments, which work with a long and variable lag, in the famous words of economist Milton Friedman. Additionally, fixed-rate debt that’s agnostic to interest rates has become more prevalent lately.

And since rate hikes haven’t crushed economic growth, there’s little reason to believe that the first few cuts will move the needle much.

“The market’s making a really big deal of upcoming Fed cuts that are expected to be kind of gradual,” Alden said in a recent interview. “At least for the first several cuts, I expect them to be relatively unimpactful for the US economy.”

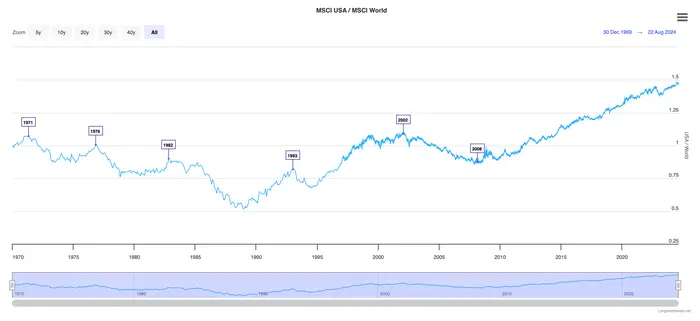

US stocks underperformed their global peers in the mid-2000s after interest rates fell.

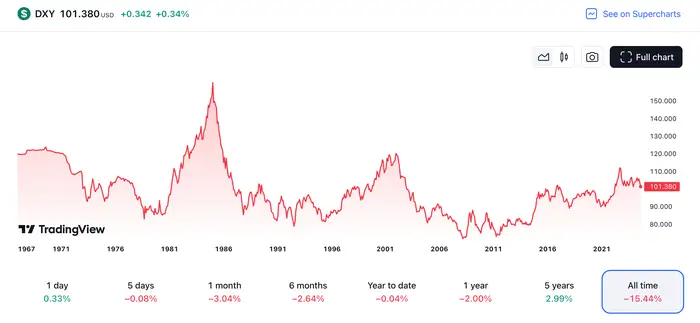

As US stocks struggled to find their footing, international companies — now unburdened by a strong dollar and the ensuing inflationary effects from it — began what became their longest stretch of outperformance since at least 1970.

“You got kind of a boom in emerging markets,” Alden said. “The dollar finally weakened to a significant degree, and then that alleviated their dollar-denominated debts.”

The similarities between that backdrop and 2024 are self-evident.

US equities are once again trading at historically rich levels after years of crushing foreign stocks, thanks to exceptional runs from large tech stocks. Global investors have scrambled to get exposure to artificial intelligence, which is said to be one of the biggest innovations since the internet. That has pushed the share of US stocks in the MSCI World Index to an astronomical 71.7%. Also, the US dollar has held up well relative to foreign currencies.

Crucially, the Fed is about to reduce rates, though this time, it’s not in response to a recession. Alden is torn between whether there will be no downturn or a mild one, though she confidently described her base case for the US economy as a lengthy period of “malaise” as growth slows.

“Should we get a recession, I would expect it to be closer the 2001 variety: unemployment going up — maybe 5%; maybe a little higher,” Alden said. “But not one of those big — everybody just has 2008 and 2020 locked into their minds.”

Lower rates won’t boost US stocks much in this tougher backdrop, Alden said. But she believes they’ll be a massive tailwind for long-burdened international companies — including firms in emerging markets. She cited Brazil and Colombia in Latin America, as well as Malaysia and Indonesia in Southeast Asia, as examples of potential beneficiaries.

“Every quarter-point cut shouldn’t really matter too much for the US market,” Alden said. “But it is pretty meaningful for emerging markets because that allows them to ease; it potentially eases their dollar debts a little bit. And so I actually view them as potentially some of the biggest benefactors from the Fed’s gradual rate-cutting intentions.”

The market reversal Alden is counting on should have come sooner, she said. Five years ago, the US central bank slowly reduced rates in a so-called “mid-cycle adjustment” that came in response to slowing growth. But the pandemic and subsequent stimulus threw everything off.

Unless there’s another black swan event, Alden expects a lower federal funds rate to strengthen international currencies compared to the US dollar. All else equal, that should support a long-awaited rebound for equities trading overseas, especially those in emerging markets.

“There’s always a risk of a false alarm,” Alden said. “You never know what’s going to happen. People couldn’t have, in 2019, have predicted COVID.”

Alden later added: “Outside of some sort of equivalent to COVID, I would say there’s a reasonable chance of this being a rotation that people in 2019 thought might happen for fairly credible reasons.”