For God, for country, for rainHow 24-year-old cloud-seeding wunderkind Augustus Doricko plans to save the world

It’s 9:30 a.m., and Augustus Doricko, the mulleted 24-year-old founder of the cloud-seeding company Rainmaker, is clutching a coffee. He and his colleagues spent the prior evening hopping from one Las Vegas hot spot to the next, gorging on “monstrously large” steaks and smoking cigars. They tried to end the night at Bruno Mars’ jazz club, The Pinky Ring, but fled due to some sort of metaphysical disturbance.

“The vibe was off,” Doricko said. “What you’ll come to find, should we get to be friends very long, Jessica, is that the vibes are of critical import.”

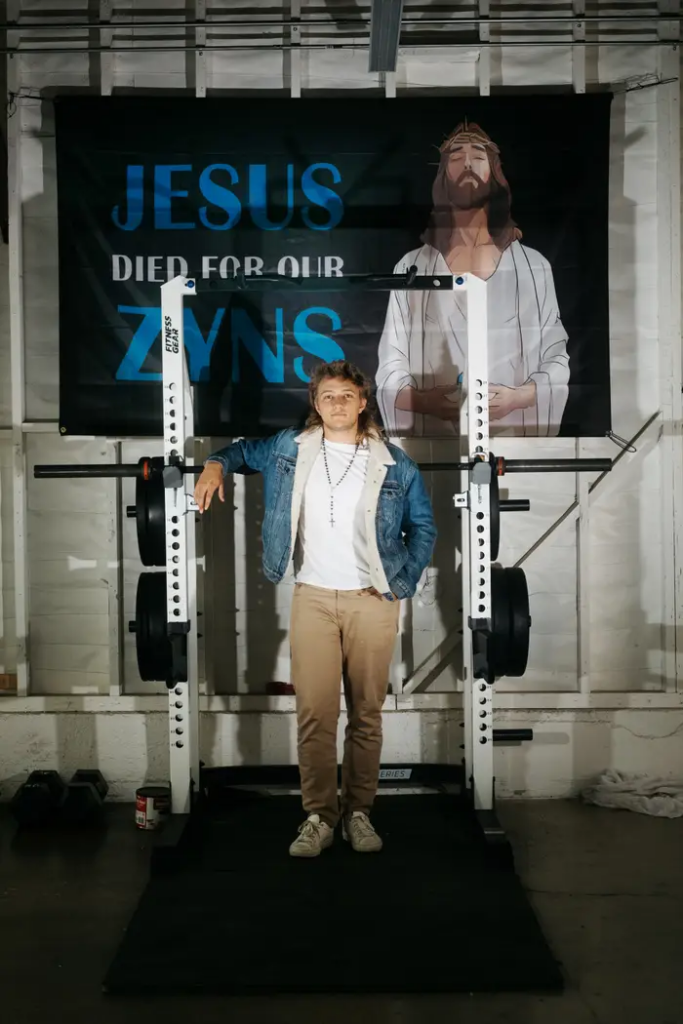

The vibes are decidedly stale at our first meeting that morning in a windowless conference room in the basement of the MGM Grand. I’d reached out to Doricko after noticing him on X, where he posts photos from his office gym, which is decorated with a “Jesus died for our Zyns” banner, as well as musings on startup life and water policy. He’d invited me to join him in Vegas in April, where he and his team were spreading the gospel of Rainmaker at the annual Weather Modification Association conference.

Amid the crowd of checkered shirts and receding hairlines, Doricko’s staff of 20- and 30-somethings, clad in matching fleeces, look like an amateur sports team that’s stumbled into the wrong room. Luckily, they have their game faces on. Rainmaker wants to revolutionize cloud seeding — the process of firing a solution, usually silver iodide, into clouds to induce precipitation or rain that wouldn’t occur naturally — by using specialized drones, radar-based weather tracking, and numerical modeling to make the process more precise, economical, and easier to deploy.

While the weather industry isn’t exactly known for pumping out celebrities, Doricko has gotten as close as it gets to a household name. This year alone, he was photographed next to Bezos Earth Fund’s vice chair, Lauren Sánchez, at Miami’s Aspen Ideas conference; flew to Tennessee to testify against a controversial chemtrail bill, which could limit cloud-seeding operations; and attended a Clinton Global Initiative dinner, where he and Bill, both wearing suits and sneakers, discussed how cloud seeding might supplement the country’s water supply.

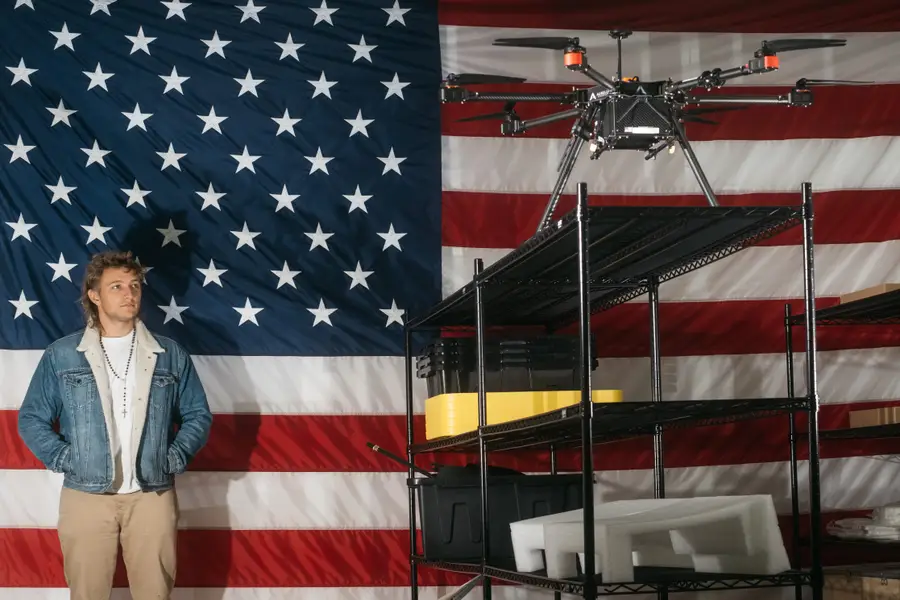

Doricko’s home base is El Segundo, a beachside suburb 30 minutes from Los Angeles that’s known as the aerospace capital of the world. Lately, the place seems full of young tech entrepreneurs who love cigarettes, America, and throwing parties in their small-scale factories. They’ve built a community set apart from Silicon Valley — one that merges techno futurism with a blue-collar aesthetic and a libertarian mindset. At its center is Doricko, who seems to know just about everyone and can be found most Sundays at Christ Church Santa Clarita where he and many of his peers do the other thing they have in common: worship God.

Doricko, far right, hosts weekly beach bonfires in El Segundo for tech founders and their hangers-on.

Doricko, who resembles a baby-faced Billy Ray Cyrus, is quick to note that being Christian isn’t a requirement for joining the El Segundo scene; everyone is welcome, “as long as you want to build something spectacular,” he said. But he also believes that if he does achieve his version of greatness — if he manages to upend the way we interact with the weather or alleviate the water shortage that scientists say is imminent — his success will be in service to something bigger. “Any technology that moves the needle on humanity’s well-being, that is something that brings us closer toward Heaven on earth,” he told me while striding across the sticky carpets of the MGM Grand.

“I view in no small part what we’re doing at Rainmaker as, cautiously and with scrutiny from others and advice from others, helping to establish the kingdom of God.”

It won’t be easy. There’s a long way to go before cloud seeding becomes a viable option for solving one of humanity’s many self-made crises. Beijing claimed to have used cloud seeding to ensure clear skies for the 2008 Olympics. And last year, the US government spent $2.4 million on a cloud-seeding program to revitalize the dwindling Colorado River. But the industry has seen little innovation since the 1970s, and some are skeptical that the process even works outside a laboratory, where things like wind patterns and topography are hard to control.

I view in no small part what we’re doing at Rainmaker as helping to establish the kingdom of God.

Doricko’s peers are certain he’s on the cusp of something big, though. His former roommate Cameron Schiller, whose company uses 3D printing to manufacture metal parts, said Doricko’s determination borders on obsession. “Augustus is going to be an individual that truly changes the world — someone that people can point to and say, ‘This person did something that stands the test of time and history,'” Schiller said.

“He really cares,” Schiller added, “and I don’t think he’ll stop until he sees greatness.”

El Segundo, population 17,272, has long been a bastion of American engineering, home to aerospace and defense giants like Boeing and Raytheon. That’s still true, but in the past four or so years, it’s been flooded with ambitious new startups, including the autonomous-defense-systems company Picogrid, the nuclear-fission company Valar Atomics, and the pharmaceuticals-in-space company Varda Space Industries.

Doricko and his self-described “Gundo Bros” are over app-based companies seeking to “disrupt” the way people catch cabs or order meals. They want to usher in a new era of American economic growth and stability that allows people to work in a “more embodied way.”

“Respect to Zuck, but I certainly hope the next cohort of people that build great things do it in the real world, and build products that really make everything radically different and better,” Doricko said, “rather than just trying to skim a little bit more efficiency off the top of the economy.”

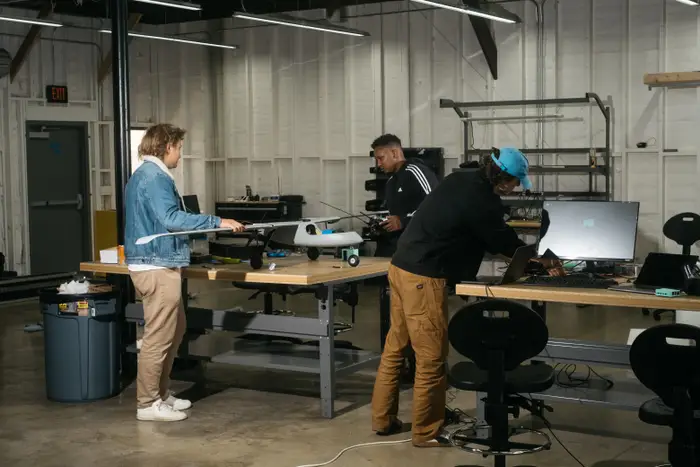

The day after the conference, we fly back to California and Doricko takes me on a tour of Rainmaker’s headquarters. On the walls, I spot two of El Segundo’s biggest American flags (and, yes, it is a competition). The largest room, for engineering, houses the drones Rainmaker uses for cloud seeding, as well as a bench press where Doricko sometimes takes interviews. In another room, desks are scattered with half-used tins of Zyn, climbing chalk, dumbbells, and a broadsword Doricko bought at an estate sale. An aerosol chemistry lab rounds out the floor, with a large, opaque bottle labeled “DO NOT DRINK” sitting in a corner. There’s an audible buzz in the air, which I later find out is the hum of the avocado-oil processing plant across the street.

In some ways, El Segundo feels like a big college campus. Doricko led me through the sunny streets to Smoky Hollow Coffee Roasters, a local staple filled with people typing away on their keyboards. We sat outside on a bench, and he told me how proud he was of his neighbors. They “are trying to enact a vision for the industry they’re in, the country that we’re in, the future of humanity — that requires radical execution,” he said. At the same time, they’re “silly, can go booze, can go burn a bunch of stuff at the beach.”

El Segundo’s founders “are trying to enact a vision that requires radical execution,” Doricko said. At the same time, they’re “silly, can go booze, can go burn a bunch of stuff at the beach.”

The burning happens every Friday around 8 p.m. at a bonfire on El Segundo Beach. (Doricko once posted an invite on X urging his followers to come watch “the finest Swedish assemblies set ablaze” and tagging Ikea.) Founders go, but so do young people from states as far away as North Carolina or Texas. They’re hoping to shake some hands, meet some people, and land a job in the Gundo by the time Monday rolls around, Doricko said.

Several hours after our coffee, Doricko and I arrived at that week’s bonfire party in his white Chevrolet pickup. The crowd, mostly white men and some women, chatter about tech, work, and Elon Musk, who’s only ever referred to by his first name. At the fire’s edge, I strike up a conversation with Isaiah Taylor, the 25-year-old founder of Valar Atomics and a friend of Doricko’s. “I can look around right now and see a lot of people that sleep in the office,” Taylor said. “It might be making it rain more, making the Earth habitable, might be making energy cheaper — we’re not apologetic about wanting to build extremely hard things for our community and country. We all love America.”

For Taylor, like Doricko, love of country is closely linked to love of God. Taylor periodically hosts community Bible study and prayer sessions and invites his fellow founders to join. Not all of them believe in God, but many do. And Doricko has a theory why: “This is a pretty rebellious group of people,” he said. “And if the zeitgeist is nihilistically secular, then the rebellious stance is to be Christian.”

Almost prophetically, much of Doricko’s childhood took place in the water. He grew up in Stamford, Connecticut, and learned to sail at the Stamford Yacht Club, where his parents were members until they separated in 2007.

He considers those years, which he often spent soaked through and freezing — once to the point of hypothermia — to be formative. His sailing coach, Rob Coutts, who won a world championship title for New Zealand, was “tough as nails,” Doricko said. “Kids would be crying, there’d be howling wind, and he’d use very choice words to tell them to get back in the boat. Most kids didn’t like him, but I loved him.”

If the zeitgeist is nihilistically secular, then the rebellious stance is to be Christian.

In high school, Doricko lived with his mom and younger sister. He stayed busy with the debate team, more sailing, and countless hours playing the video game “Spore,” which he used to turn barren planets into diverse and sophisticated ecosystems. He’d hoped to become an astronaut, but his plans were scuppered when a swim in a Costa Rican bog ruptured his right auditory nerve, leaving him deaf in one ear. Instead, he went to the University of California, Berkeley, as a physics major.

By the end of his first year, he was disillusioned, frustrated at the prospect of spending decades doing research to move the scientific needle forward even a millimeter. He started to get restless. Then, Doricko found God.

It began because his love of absurdist philosophers — who posit that everything in life is random and irrational — started to drive him mad. His classmates seemed comfortable with the idea that their lives were of no moral consequence, but Doricko, who hadn’t grown up religious, ironically found the idea “insufferable.” He started to think that if life was truly meaningless, there was no reason not to pursue a path of “reckless hedonism.” Things came to a head one day in January 2020, when he walked past several homeless people on the streets of Berkeley. “I was starting to think, ‘Well, it’s entirely possible to end up like them, and there’s no reason not to,'” he said.

That moment sent him on a frantic search for meaning; he spoke to two nondenominational pastors, a Catholic priest, a Sunni imam, and two rabbis. He seriously considered converting to Judaism, but eventually, inspired by historical accounts of Jesus of Nazareth, he settled on Christianity. “Believing that something, someone, God, loved me no matter my faults — desired that I improve upon my faults, but loved me in spite of them — that was earth-shaking,” Doricko told me.

Still, some of his views put him at odds with the average Gen Zer. “I have and I love plenty of friends that are gay or that are very pro-choice, and I’ll continue to,” Doricko said. But “I don’t know if those are the things that our Lord wants for us.”

In October 2020, Doricko moved to Fort Worth, Texas, to attend Berkeley remotely. He dove into Bible study while simultaneously crafting his powerlifting, milk-drinking, gym-bro persona. At Berkeley, he’d been clean-cut and preppy — a style he saw as a “rebellion” against omnipresent athleisure. But these days he’s more likely to sport shearling-lined denim jackets, Jesus-themed T-shirts, and sweats. “My aesthetic preferences are just trying to push the needle on what we can look like,” he explained. “Because if we stay the same, we stay the same, and the current condition is not good.”

Rainmaker’s office is a reclaimed warehouse, which includes a gym where Doricko sometimes takes interviews.

Doricko started weight training with the entrepreneur Jason Flynt, one of the biggest water-well drillers in Texas. As they worked out together, Doricko learned about Flynt’s business, and by November 2020, Flynt offered him a contracted project: writing code to help digitize elements of the well-pumping process. The project went so well that a year later, Doricko and Flynt launched Terra Seco, a company that automated regulatory compliance and monitoring for groundwater wells.

Doricko left Berkeley in 2022, just two months shy of graduating, to focus on Terra Seco full time. But even then, he knew that the company’s efforts weren’t enough to solve the issue of water scarcity. He spent the better part of a year researching what he saw as the real solution: conjuring water out of thin air.

During that time, he read the book “Paper Belt on Fire,” by the former Thiel Foundation executive Michael Gibson, which lists cloud seeding as one of the 100 technologies that will shape the future. That led Doricko to the 2023 Weather Modification Association conference, where he watched the scientist Sarah Tessendorf’s presentation on the SNOWIE project: the first-ever quantitative study proving that cloud seeding worked. Doricko sold off his shares in Terra Seco and messaged Gibson on X. “I was like, ‘Michael, Michael, Michael. I figured it out. I know how we can make cloud seeding real,'” he said. “Then I read more about it, and I was like: ‘Oh, this is way more complicated.'”

Gibson — whose venture-capital firm, 1517 Fund, backs “college dropouts and sci-fi scientists” — was impressed by Doricko’s industry knowledge, but he was truly won over by his charisma. “We meet a lot of engineers who can build a great many things, but they’re terrible at working with people,” Gibson said. “Augustus both had the engineering and the smarts to actually run this company.” In April 2023, Gibson’s fund invested $100,000 in Rainmaker. The next year, it forked over another half-million dollars.

That same year, Doricko also landed a Thiel fellowship, bestowed upon tech’s brightest college dropouts, which comes with $100,000 and a two-year networking and mentorship program. Like Peter Thiel himself, Doricko is happy to talk about how school is a waste of time. “There’s so much opportunity out in the world. Why would I spend my time studying for a test?” he said. “I’m not going to go through the indignity of accepting a credential from somebody to prove that I’m a capable member of the workforce.”

When asked how he first learned to code, Doricko laughed. “Uh, classes,” he said. “Classes at university.”

With Rainmaker, Doricko has taken on a rather complex problem. Numerous studies before the SNOWIE project produced inconclusive results about cloud seeding’s efficacy, and some scientists worry that it may not work at all or, at the very least, may be useless against extreme weather events like droughts.

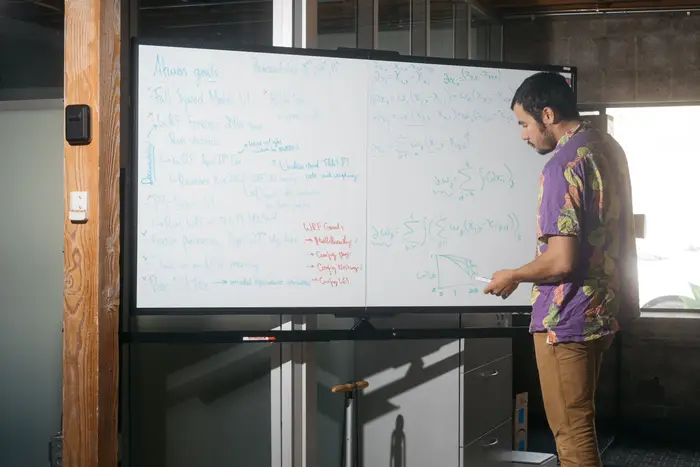

Katja Friedrich, an atmospheric scientist, says many existing cloud-seeding programs rely on measurements taken by small, twin-engine airplanes to determine when and where to seed clouds. These same planes then fire the flares containing the iodide solution. Both processes are easily thrown off by variables like wind speed and rapidly changing temperatures.

Rainmaker wants to do away with the planes altogether and replace them with drones, which would be much cheaper. (Plane-based cloud-seeding operations typically cost thousands of dollars an hour, but Doricko claims Rainmaker’s cost about $20 an hour for the same level of coverage, in part because the drones rely on electricity instead of fuel.)

Rainmaker has cycled through dozens of drone models as they seek to reimagine cloud seeding.

But Friedrich warns that this isn’t a perfect solution, pointing to obstacles like FAA regulations, drone battery life, and collecting accurate measurements from the drones, which can’t carry as much monitoring equipment. Friedrich isn’t the only one who’s skeptical. While Jonathan Jennings, who oversees Utah’s cloud-seeding program and serves as president of the Weather Modification Association, is a Doricko fan in general, he said that “there’s always going to be a human element that I want to see in the field. So I’m a little resistant to drones in most cases.”

Doricko isn’t deterred. For one thing, he claims that the industry-wide aversion to drones is, in part, financially motivated because business owners don’t want to spend money to update their technology. “There is momentum and vested interest in what are potentially less efficient modes of delivery,” he said. Plus, he has a planet to save. Just look at the dwindling levels of water in the Colorado River Delta; the enormous drops in drawdowns from Lake Mead, Las Vegas’ primary water source; and housing development bans in Phoenix, which no longer has enough water to support new inhabitants. “I would certainly prefer a world where we at least can avert catastrophe,” Doricko said, “to a world where we just have a slow, whimpering death and march toward said catastrophe.”

Doricko currently has a team of 23 people, including Kaitlyn Suski, an aerosol scientist who used to work at Juul. Suski is developing an alternative nucleation agent to silver iodide that Rainmaker eventually hopes to patent. (Exposure to large amounts of silver iodide can cause symptoms like vomiting and respiratory issues, and while cloud seeding uses so little that the likelihood of side effects is thought to be minuscule, Doricko wants to get ahead of the problem.)

Rainmaker employees’ desks are scattered with tins of Zyn, climbing chalk, and dumbbells.

Other Rainmaker employees are creating anti-icing systems that will allow drones to fly as close as possible to clouds filled with supercooled liquid, which provide the best possible conditions for cloud seeding. They’re also honing their radar and lidar processing to monitor how much rain is produced by each cloud-seeding attempt. In theory, all of this will make cloud seeding easier, more accessible, and more commercially viable.

On a sunny Saturday, I accompany Doricko and Jackson Schultz, the head of engineering, to a 6,000-acre farm about an hour south of Fresno where the company tests its drones. They’re cycling through different models, sussing out which supplier can provide one ideal for flying through clouds. Today’s choice, named Elijah, is a robust model with a 6-foot wingspan.

Out in the field, along with the breeze and the birdsong, you can hear the occasional whirring of Elijah’s engine as it struggles to take off. The drone’s tiny wheels — a hallmark of this particular model — are getting tripped up by the farm’s rocky terrain, preventing it from gaining enough speed for flight.

Doricko and Schultz drive around for a while looking for a new launch site: someplace where the ground is smoother. Eventually, though, they run out of time. Schultz has to go to San Jose to pick up his new car, a vintage green Corvette.

The next day, we head to church. We’re joined by Isaiah Taylor, the Valar Atomics founder, and a few others from Friday night’s bonfire. After the service, everyone spills out onto the grass, grabbing coffees from a folding table and chattering under a cloudless sky.

Eventually, Taylor and Doricko want to build their own church in El Segundo: a dedicated house of worship for the young tech elite. They want to strengthen the bonds of their already close-knit community — give their peers the gift they’ve discovered for themselves. “If I can help, through creating a church, share the grace of God with other people, that would be one of the biggest blessings I’ll have ever undertaken,” Doricko said.

That night, Doricko will fly to Dubai to speak to UAE government officials about its national cloud-seeding program, which some scientists think contributed to flash floods that killed four people. Doricko considers himself a bit of a fanboy of Dubai’s work. The fact that the city is “now bringing more water to the desert than their ancestors ever could have prayed for is super exciting,” he said.

One of Doricko’s goals is to build a church in El Segundo to “share the grace of God with other people.”

Doricko’s plans are equally ambitious. He wants to extend the Great Plains from the Midwest through West Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California, blanketing the Western states in lush, arable land capable of supporting communities. “We have this planet that we can turn into a garden,” he says. In his eyes, protecting that planet — and preventing climate disaster — is God’s will. “Mankind was made to take care of and tend to the garden and make it grow well and flourish,” he said. “That extends to now, right? It’s in our nature to take dominion and be generative with it.”

Ultimately, Doricko hopes to turn El Segundo into something like Amsterdam during the Enlightenment, or Milan during the Renaissance. But that all depends on whether companies like Rainmaker have staying power. “The reputation of the Gundo will very much live or die by the success of these startups,” Gibson, the early Rainmaker investor, said. If they fail, “all this countercultural stuff will have faded out, because the companies just didn’t make it.”

Gibson believes that Doricko has enough “gusto” and “love of the fight” to make it happen. But his faith isn’t blind.

Doricko “has said sometimes, ‘I think God is on our side,'” Gibson said. “And I’ll say: ‘Yeah, but the Lord works in mysterious ways.'”