Google, Microsoft, and others are racing to crack open quantum computing. Here’s how their breakthroughs stack up.

The quantum race is heating up.

Tech titans Amazon, Google, IBM, and Microsoft each recently announced advancements in their prototype chips, tightening the race to develop a commercially useful quantum computer that could solve some of the universe’s stickiest problems faster than a classical computer ever could.

Quantum computing is a rapidly evolving — though still largely theoretical and deeply technical — field. But cracking it open could help discover new drugs, develop new chemical compounds, or break encryption methods, among other outcomes, researchers say.

Naturally, each of the major players in Big Tech wants to be the one to take quantum computing mainstream.

“You’re hearing a lot about it because this is a real tipping point,” Oskar Painter, the director of quantum hardware at Amazon Web Services, told B-17 in late February, following the company’s announcement of its Ocelot chip.

Stick with us — here’s where it gets complicated.

Where classical computing uses binary digits — 0s and 1s, called bits — to represent information, quantum computing relies on a foundation built from the quantum equivalent of bits, called qubits. When they behave predictably at a large enough scale, qubits allow quantum computers to quickly calculate equations with multiple solutions and perform advanced computations that would be impossible for classical computers.

However, qubits are unstable, and their behavior is unpredictable. They require specific conditions, such as low light and extremely cold environments, to reduce errors. When the number of qubits is increased, the error rate goes up — making advancement in the field slowgoing.

Small-scale quantum computers already exist, but the race is on to scale them up and make them useful to a wider audience rather than just scientists.

Recently, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have announced new prototype chips, and IBM has made strides in its existing quantum road map. Each company is using unique approaches to solve the error reduction and scalability problems that have long plagued the field and make useful quantum computing a reality.

Here’s how each approach stacks up.

Microsoft

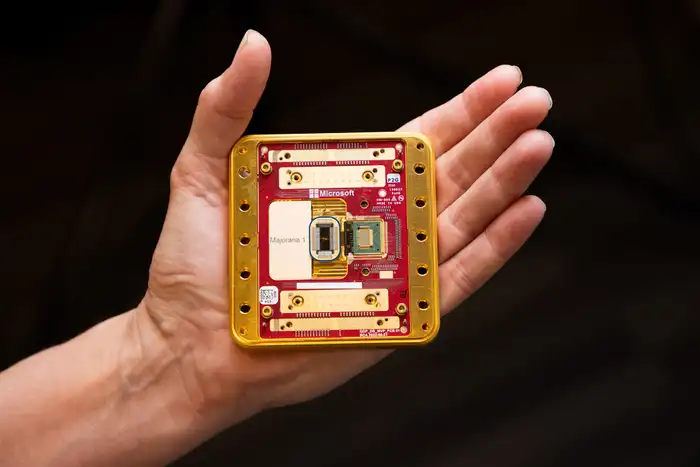

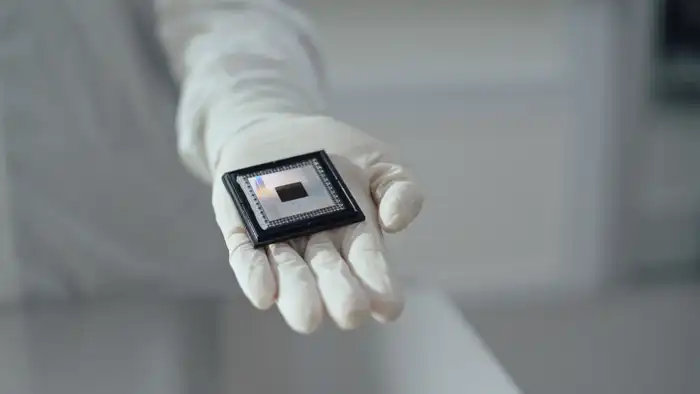

Microsoft’s Majorana 1 chip is the first quantum computing chip powered by topological qubits.

Approach to quantum: Topological qubits

Most powerful machine: Majorana 1

In February, Microsoft unveiled its new quantum chip, Majorana 1. The aim is for the chip to speed up the development of large-scale quantum computers from decades to years.

Microsoft said the chip uses a new state of matter to produce “topological” qubits that are less prone to errors and more stable. Essentially, this is a qubit based on a topological state of matter, which isn’t a liquid, gas, or solid. As a result, these quantum particles could retain a “memory” of their position over time and move around each other. Information, therefore, could be stored across the whole qubit, so if any parts fail, the topological qubit could still hold key pieces of information and become more fault-resistant.

“Microsoft’s progress is the hardest to get an idea about because it’s very niche,” said Tom Darras, founder of quantum computing startup Welinq. “Even experts in the industry find it difficult to assess the quality of these results.”

Quantum experts agree that Microsoft still has many roadblocks to overcome, and its peer-reviewed Nature paper only demonstrates aspects of what its researchers have claimed to achieve — but some in the quantum ecosystem see it as a promising outcome.

Google researchers are aiming to reverse a long-standing qubit problem.

Approach to quantum: Superconducting qubits

Most powerful machine: Willow

In December, Google announced Willow, its newest quantum chip, which the company claims takes just five minutes to solve a problem that would take the world’s fastest supercomputer 10 septillion years.

Perhaps more impressive was Google’s breakthrough in how quantum computers scale. Historically, the more qubits that are added, and the more powerful the computer becomes, the more prone it is to errors. With Willow, Google’s researchers said that adding more physical qubits to a quantum processor actually made it less error-prone, reversing the typical phenomenon.

Known as “below threshold,” the accomplishment marks a significant milestone by cracking a problem that has been around since the 1990s. In a study published in Nature, Google’s researchers posit this breakthrough could finally offer a way to build a useful large-scale quantum computer. However, much of this is still theoretical, and now Google will need to prove it in practice.

Amazon

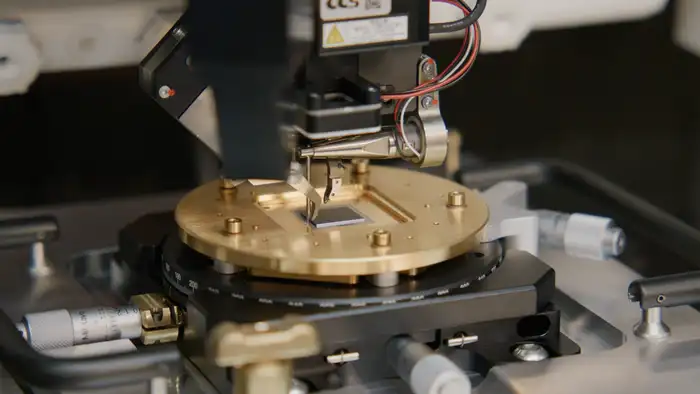

A superconducting-qubit quantum chip being wire-bonded to a circuit board at the AWS Center for Quantum Computing in Pasadena, Calif.

Approach to quantum: Superconducting qubits

Most powerful machine: Ocelot

In late February, Amazon Web Services announced its Ocelot chip, a prototype designed to advance the company’s focus on cloud-based quantum computing.

An Amazon spokesperson told B-17 the Ocelot prototype demonstrated the potential to increase efficiency in quantum error correction by up to 90% compared to conventional approaches. The chip leverages a unique architecture that integrates cat qubit technology — named for the famous Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment — and additional quantum error correction components that can be manufactured using processes borrowed from the electronics industry.

Troy Nelson, a computer scientist and the chief technology officer at Lastwall, a cybersecurity provider of quantum resilient technology, told B-17.

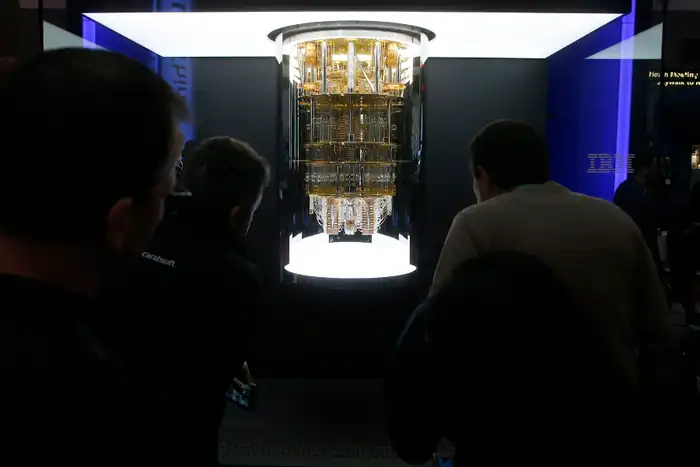

CES patrons take a look as IBM unveils this quantum computer, Q System One.

Approach to quantum: Superconducting qubits

Most powerful machine: Condor

IBM has been a quantum frontrunner for some time, with several different prototype chips and its development of Q System One, the first circuit-based commercial quantum computer, unveiled in January 2019.

IBM’s Condor chip is the company’s most powerful in terms of its number of qubits. However, since its development, IBM has focused its approach on the quality of its gate operations and making its newer quantum chips modular so multiple smaller, less error-prone chips can be combined to make more powerful quantum computing machines.

Condor, the second-largest quantum processor ever made, was unveiled at the IBM Quantum Summit 2023 on December 4, 2023. At the same time, IBM debuted its Heron chip, a 133-qubit processor with a lower error rate.

Rob Schoelkopf, cofounder and chief scientist of Quantum Circuits, told B-17 that IBM has prioritized “error mitigation” over traditional error correction approaches. While IBM has so far been successful in what Schoelkopf calls “brute force scaling” with this approach, he said the methodology will need to be modified in the long run for efficiency.

Who leads the race?

Sankar Das Sarma, a theoretical condensed matter physicist at the University of Maryland, told B-17 that the Amazon Web Services Ocelot chip, Google’s Willow, and IBM’s Condor use a “more conventional” superconducting approach to quantum development compared to other competitors.

By contrast, Microsoft’s approach is based on topological Majorana zero modes, which also have a superconductor, but in “a radically different manner,” he said. If the Majorana 1 chip works correctly, Das Sarma added, it is protected topologically with minimal need for error correction, compared to claims from other tech companies that they have improved conventional error correction methods.

Still, each company’s approach is “very different,” Das Sarma said. “It is premature to comment on who is ahead since the whole subject is basically in the initial development phase.”

Big Tech companies should be cautious about “raising expectations when promoting results,” said Georges-Olivier Reymond, CEO of quantum computing startup Pasqal. “Otherwise, you could create disillusionment.”

Reymond’s sentiment was echoed by IBM’s VP of quantum adoption and business development, Scott Crowder, who told B-17 he is concerned “over-hype” could lead people to discount quantum technology before its promise can be realized.

“We think we are on the cusp of demonstrating quantum advantage,” said Crowder, referring to when a quantum computer outperforms classical machines. “But the industry is still a few years from a fully fault-tolerant quantum computer.”