Health workers warn loosening mask advice in hospitals would harm patients and providers

Nurses, researchers, and workplace safety officers are concerned that new CDC guidelines will reduce protection against the coronavirus and other airborne pathogens in hospitals.

This year, a CDC advisory committee is updating its 2007 standards for infection control in hospitals. Many doctors and scientists were outraged when the group released a draft of its proposals in June.

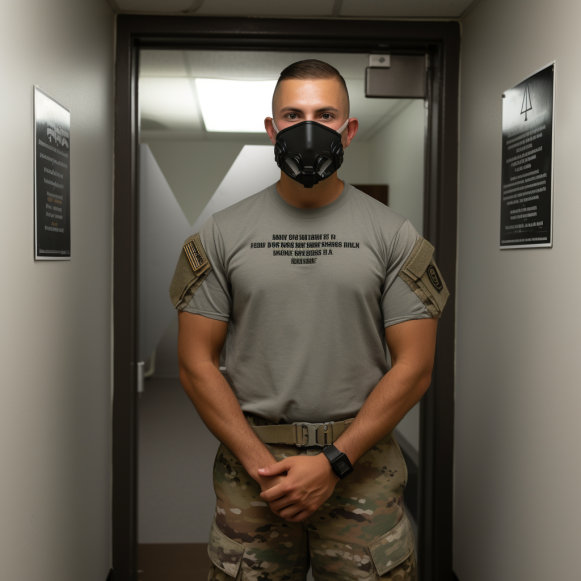

In certain settings, the draft concluded that N95 face masks are equivalent to looser, surgical face masks — and that doctors and nurses must wear only surgical masks when treating patients infected with “common, endemic” viruses, such as those that cause the seasonal flu.

The committee was supposed to vote on the changes on August 22, but it pushed it back to November. Once the advice is finalized, the CDC begins the process of converting the committee’s recommendations into guidelines that hospitals across the country typically follow. Following the meeting, members of the public expressed concern about the CDC’s direction, particularly as COVID-19 cases increased. For several weeks, hospital admissions and deaths due to COVID have been increasing across the country.

“Health care facilities are where some of the most vulnerable people in our population have to frequent or stay,” Gwendolyn Hill, a research intern at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said following the committee’s presentation. N95 masks, ventilation, and air-purifying technology, she claims, can reduce COVID transmission within hospital walls and “help ensure that people are not leaving sicker than they came.”

“We are very happy to receive feedback,” said Alexander Kallen, chief of the Prevention and Response Branch in the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. “Our goal is to create a guideline that protects patients, visitors, and health workers.” He also stated that the draft guidelines are far from complete.

Members of the CDC’s Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee presented a draft of their report in June, citing studies that found no difference in infection rates between health providers who wore N95 masks in the clinic versus surgical masks. They discovered flaws in the data. Many of the health workers who got COVID in the trials, for example, were not infected while wearing their masks at work. Nonetheless, they concluded that the masks were equivalent.

Their findings contradict the CDC’s 2022 report, which found that wearing a N95 mask reduces the chances of contracting the coronavirus by 83%, compared to 66% for surgical masks and 56% for cloth masks. It also disregards a large clinical trial published in 2017 that found N95 masks to be far superior to surgical masks in protecting health workers from influenza infections. It also contradicts an extensive study conducted by the Royal Society, the United Kingdom’s national academy of sciences, which discovered that N95 masks, also known as N95 respirators, were more effective against COVID than surgical masks in health care settings worldwide.

“It’s shocking to suggest that we need more studies to know whether N95 respirators are effective against an airborne pathogen,” said Kaitlin Sundling, a physician and pathologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, after the June meeting. “The science behind N95 respirators is well established, and it is based on physical properties, engineered filtered materials, and our scientific understanding of how airborne transmission works.”

Her claim is supported by the California Occupational Safety and Health Administration, whose rules on protecting at-risk workers from infections may conflict with the CDC’s if the proposals are adopted. At the August meeting, Deborah Gold, an industrial hygienist with Cal/OSHA, said, “The CDC must not undermine respiratory protection regulation by making the false and misleading claim that there is no difference in protection” between N95 masks and surgical masks.

The committee’s classification of airborne pathogens also perplexed researchers and occupational safety experts. Instead of a N95, a surgical mask was proposed as protection for a category they created for “common, endemic” viruses that spread over short distances and “for which individuals and communities are expected to have some immunity.” Researchers Hilary Babcock, Erica Shenoy, and Sharon Wright were among the authors of a June editorial arguing that hospitals should no longer require all health care workers, patients, and visitors to wear masks. “The time has come to deimplement policies that are not appropriate for an endemic pathogen,” they wrote.

In a phone interview with KFF Health News, Kallen clarified that the committee included coronaviruses that cause colds in that category, but not the coronavirus that causes COVID.

The committee’s next tier included viruses in a “pandemic-phase,” which occurs when the pathogen is new and there is little immunity through infection or vaccination. It was suggested that health workers wear a N95 mask when treating patients infected with this type of bug. Its third and highest tier of protection was reserved for pathogens like measles and tuberculosis, which they claimed could spread further than lower-tier threats and necessitated a N95.

According to virologists, the committee’s categories have little biological validity. The mode of spread of a pathogen is unaffected by its prevalence; common viruses can still harm vulnerable populations; and many viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, can travel long distances on microscopic droplets suspended in the air.

“Large COVID outbreaks in prisons and long-term health care facilities have demonstrated that the behavior of infectious aerosols is not easily classified, and these aerosols are not easily confined,” wrote Eric Berg, Cal/OSHA’s deputy chief of health, in a letter of concern to the CDC committee obtained by KFF Health News.

The committee weighed the benefits of N95 masks against their drawbacks. Its draft cites a Singapore study in which nearly a third of health care personnel, mostly nurses, reported that wearing such masks interfered with their work, causing acne and other problems exacerbated by hot and humid conditions and long shifts. Rather than discarding the masks, the study’s authors advocate for better-fitting masks and rest breaks.

Noha Aboelata, MD, CEO of Roots Community Health Center in Oakland, California, concurs. “There are other strategies to bring to bear, like improved mask design and better testing,” she explained, “if we decide it’s unacceptable to give a patient COVID when they go to the hospital.”

In July, hundreds of doctors, researchers, and others signed a letter to CDC Director Mandy Cohen, expressing concern that the CDC committee would weaken hospital safeguards. They also warned that reducing the use of N95 masks could have an impact on emergency stockpiles, leaving doctors and nurses as vulnerable as they were in 2020, when mask shortages fueled infections. According to a joint investigation by KFF Health News and The Guardian, more than 3,600 health workers died in the first year of the pandemic in the United States.

Concerned clinicians are hoping that the committee will reconsider its report in light of new research and perspectives before November. Rocelyn de Leon-Minch, an industrial hygienist for National Nurses United, said of the draft, “If they end up codifying these standards of care, it will have a disastrous impact on patient safety and our ability to respond to future health crises.”