How investors should navigate the S&P 500 likely trailing bonds and inflation for the next decade, according to Goldman Sachs

The S&P 500’s bullish run over the past year, with an over 38% return, may come at the expense of its future performance, according to Goldman Sachs.

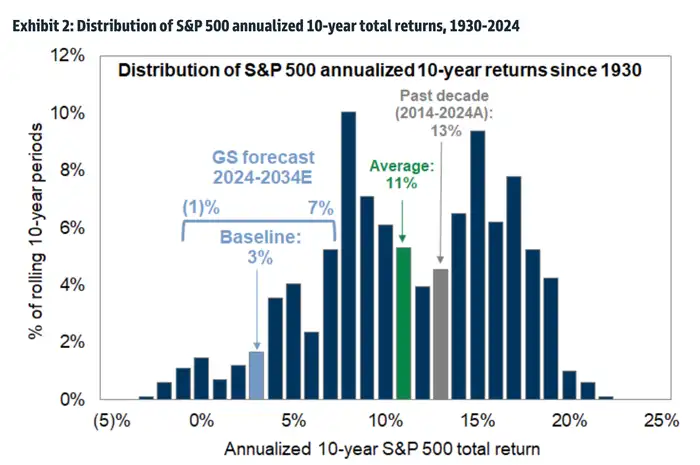

An October 18 note, led by David Kostin, forecasts muted gains for the foreseeable future. The index could post an annual return of only 3% over the next 10 years; it’s well below the average consensus estimate of 6% based on 21 asset managers tracked by the investment bank. Still, all outlooks look grim: in comparison, the index posted a 13% average annualized return over the past decade. The bank’s most bearish scenario would see the S&P 500 decline by an annual 1%, while its more positive calls for a gain of 7%.

You can thank the dominance of a small group of mega-cap tech stocks. Investor enthusiasm for the prospects of AI has cornered them into a handful of names, bringing the index’s concentration to its highest in over 100 years, the note reads. That can make things a bit shaky at the top, especially since the attractiveness of AI darlings like Nvidia rides on hypergrowth and wide profit margins. The catch-22 of this type of setup is that such extreme growth comes in bouts followed by periods of normalization.

Even if the AI darlings remain on the top for the next decade, they may not be able to sustain the same growth margins, which is the reason investors are willing to pay a premium for them.

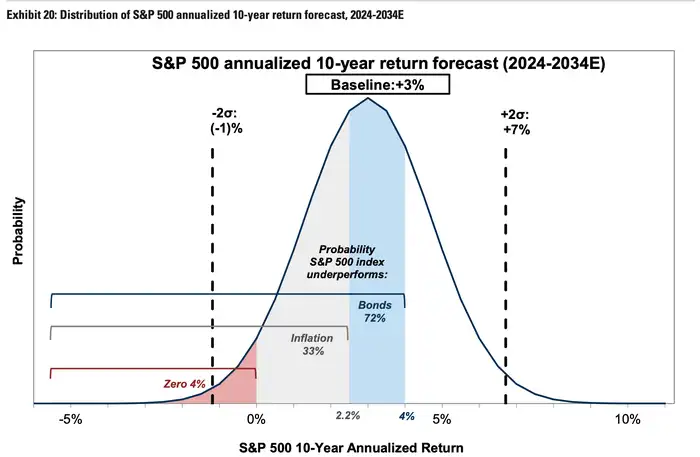

The forward-looking outlook of 3% is so muted that even lower-risk bonds, like the 10-year Treasury, are expected to outperform with a 4% yield. Goldman pegs the likelihood that bonds will beat the index over the next 10 years at a whopping 72% probability.

There’s also a 33% chance the index won’t outpace a 2.2% inflation rate. While it’s a much lower probability, it’s still at more than double the historical average of 13%. Even if it outperforms inflation, the base case would only provide real returns of 1%.

The chart below shows the distribution of returns on the index since 1930, demonstrating the rarity of such muted expectations.

Indeed, it’s a rare outlook considering that since 1930, equities underperformed the 10-year Treasury in only 13% of the time on a rolling 10-year basis, according to the note. The chart below shows the range of outcomes for the index’s performance relative to bonds and inflation.

So what should investors do?

The key word moving forward will be diversification.

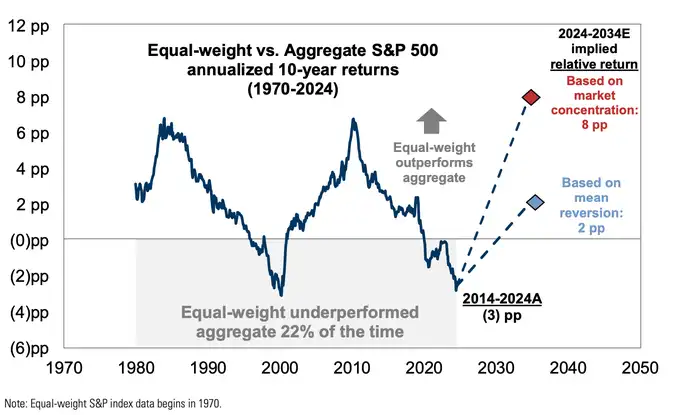

The timing could be ripe for a rotation to broader market exposure. Simply put, history shows that the equal-weighted S&P 500, which spreads the contribution of each stock to the basket’s overall performance equally, outperforms the aggregate index over the long term. This outperformance is even sharper in the periods that follow peak stock-market concentration. This was the case during the 10 years following the bear market of 1973 and the dot-com bubble of 2000, according to the note.

The chart below demonstrates the annualized 10-year returns of the equal-weighted S&P 500 relative to the aggregate one, with returns fairing better in the former on a long-term outlook and in sharper bouts following peaks of elevated concentration.

Adding an exchange-traded fund that tracks the equal-weighted S&P 500 could be one way to go about it. This also means investors will increase their exposure to small-cap stocks, another perk in a reversion-to-the-mean type scenario, where this sector has room to catch up.

Furthermore, investors should consider a more mixed asset portfolio of stocks and bonds without tilting toward one more than the other. This would create better risk-adjusted returns. Factoring in the types of yields across bonds is another option. Consider the 10-year US Treasury at a yield of 4%, investment-grade bonds at 4.8%, and high-yield bonds at a 7% yield.

Finally, be open to readjusting the allocation tilt based on macroeconomic shifts. This flexibility is referred to as a “strategic tilt,” according to a May 28 note led by the head of asset allocation research, Christian Mueller-Glissmann. For example, in an environment where economic growth is strong but there’s a risk of inflation, leaning more into equities, especially stocks with strong cash flows, may be the right direction. Meanwhile, if growth is slowed and inflation is muted, consider further allocation to bonds.