How the courts have sanctioned extreme violence by prison guardsThe Supreme Court decided in the 1980s that brutal force by corrections officers is acceptable as long as it isn’t “malicious and sadistic.”

New York law enforcement officers in riot gear after they regained control of prisoners following the Attica prison revolt in September 1971. The retaking killed 39 people. A federal judge found law-enforcement actions were not “malicious and sadistic.”

It rained heavily the night before the retaking of New York’s Attica Correctional Facility. A guard, William Quinn, had been killed. Negotiations had ended. The men on the D yard waited for the inevitable.

Four days earlier, on September 9, 1971, 1,281 prisoners had wrested control of Attica, taking 42 prison staffers hostage and delivering a manifesto demanding humane treatment including adequate healthcare, independent oversight, and an end to racial discrimination.

“We are men,” said L.D. Barkley, one of the leaders of the revolt. “We are not beasts, and we do not intend to be beaten or driven as such.”

In the early-morning light on September 13, men in D yard heard the thrum of a helicopter as it flew over Attica’s 30-foot stone walls and flooded the yard below with tear gas. Steady gunfire from ground forces tore through the gas clouds, chipping the concrete and shredding the bodies of hostages and prisoners alike. Terrified, the men desperately searched for cover. They found none. One prisoner was shot 12 times at close range by two separate guns. Another lay dying of a gunshot wound when a New York state trooper stepped up to finish him off, firing buckshot directly into his neck. A paramedic later testified he saw a trooper execute a prisoner begging for help at point-blank range. State troopers and corrections officers fired nearly 400 shots, killing 39 people — 29 prisoners and 10 prison staff — and wounding 89 more.

The surviving prisoners were corralled and moved to A yard, stripped, and ordered to lie face down in the mud. If they moved, troopers beat them and threatened to shoot them where they lay. Hours later, still naked, they were ordered to stand and run, hands above their heads, through what judges would later refer to as the “gauntlet” — a tunnel leading inside that was lined with troopers and corrections officers. They struck prisoners with clubs and hurled racist epithets. Many prisoners stumbled to the ground and ended up crawling on pavement littered with shattered glass. Once inside, officers threatened some prisoners with castration. Others they forced to play Russian roulette with live ammunition or lined up against the wall in mock executions.

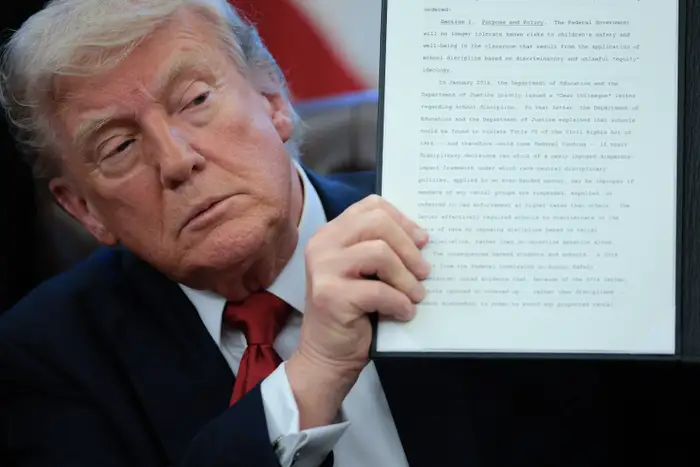

It took nearly three decades for the surviving D yard prisoners to reach a final resolution on their claims that those nightmarish days and nights constituted “cruel and unusual punishments,” in violation of the Eighth Amendment. In the intervening period, a series of new laws and legal standards changed the landscape for incarcerated plaintiffs. The Supreme Court introduced one standard in 1976, further codified in 1994, that prison officials violate the Constitution only when they are “deliberately indifferent” to a prisoner’s suffering. And in 1986, the court granted broad protections to law enforcement, as long as their actions were not “malicious and sadistic.” Guards, the justices found, often had to make decisions “in haste, under pressure, and frequently without the luxury of a second chance.”

In 1986, the Supreme Court granted broad protections for the use of force by prison staff, as long as their actions were not “malicious and sadistic.”

One set of claims, over the failure of New York’s corrections commissioner, Russell Oswald; Attica’s warden, Vincent Mancusi; and other senior officials then in charge to provide adequate medical care and prevent retaliatory violence by officers after the uprising was quelled, was decided on the new deliberate-indifference standard. Those claims settled in 2000 without state officials admitting any wrongdoing; damages were capped at $10,000 for anyone not subject to torture, serial beatings, or gunshot wounds.

Another set of claims, covering the planning and execution of the retaking itself, was decided in 1991 on the malicious-and-sadistic standard. The plaintiffs’ lawyers argued that the standard had been met, as defendants were responsible for the “wanton infliction of pain and suffering for the purposes of ‘maliciously and sadistically’ punishing rebellious prisoners.”

The judges of the 2nd Circuit disagreed. Aspects of the plan, such as declining to give prisoners an ultimatum before opening fire or allowing correctional officers to participate in the retaking “despite the extreme hostility the officers bore toward the prisoners as a result of the takeover,” might constitute negligence or even indifference, Judge Jon O. Newman wrote. But that was not enough, without evidence that those elements were designed to wantonly inflict pain. “Tactical decisions needed to be made,” he wrote, and courts cannot substitute their own judgment for that of law enforcement officials on the ground.

One of the most infamous campaigns of state violence against incarcerated people in US history did not, in the eyes of the court, constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

A lone prisoner victory

Senior corrections officials agree that physical force is sometimes necessary to maintain order and safety for both staff members and the prisoners in their care. If prisoners are harming themselves or another person, for example, quick intervention can be critical.

Training documents B-17 obtained from 37 state departments of correction show that officers in most states are guided to use the minimum amount of force necessary to maintain order. Many departments train officers on de-escalation techniques meant to defuse violence before force is necessary and instruct them to use force “only as a last resort.”

But in the 50 years since the Attica uprising, many corrections departments have failed to check staff violence when it tips into excess. Government oversight reports and journalistic investigations over the years have documented systemic abuse in multiple state prison systems: guards brutalizing incarcerated people in New York state, a pattern of sexual assault committed by prison staff in California, and a culture in Alabama prisons in which “unlawful uses of force” were common, including two beating deaths by staff in 2019 alone.

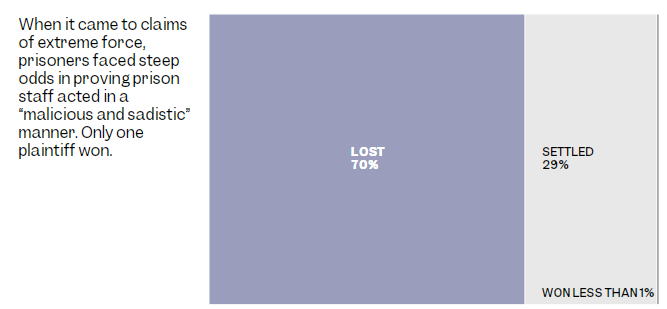

In the face of these institutional failures, federal courts have declined to step into the breach. B-17analyzed a sample of nearly 1,500 Eighth Amendment lawsuits, including every appeals court case with an opinion we could locate filed from 2018 to 2022 citing the relevant precedent-setting Supreme Court cases and standards. Of these, 208 cases involved claims of excessive force.

In 2017, Mario Gonzalez filed suit claiming that four officers at California’s New Folsom prison cornered him in his cell and kicked him in the ribs, torso, back, and groin. His case was dismissed repeatedly over six years.

In analyzing these cases, B-17 found that courts have often sanctioned extreme acts of violence by guards against prisoners. Dozens of plaintiffs in B-17 sample said they were beaten while immobilized in restraints. Another dozen said they were subjected to racist abuse or threatened with retaliatory violence. Others said they were placed in life-threatening chokeholds or hit with plastic or rubber bullets shot at such high velocity they cracked femurs and skulls. Multiple people said they were sexually abused by prison staff, including two while in restraints. All of these plaintiffs lost their cases.

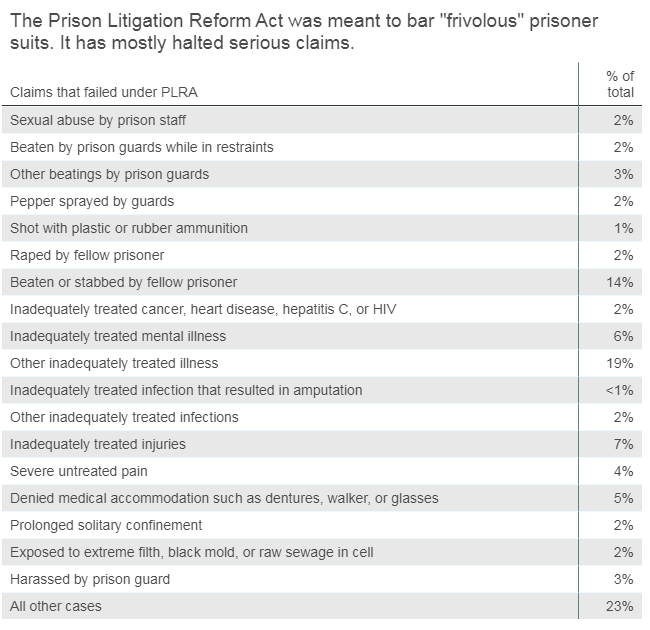

Judges dismissed many excessive-force claims under strict administrative requirements imposed by the Prison Litigation Reform Act, a 1996 federal law designed to curb “frivolous” prisoner lawsuits. Judges dismissed others for failing to meet the malicious-and-sadistic standard, or due to doctrines that protect law enforcement officials like prison guards. Judges rarely questioned the authority of prison staff to determine when a use of force was justified.

Sixty-one of the excessive-force cases, almost a third, settled. Only one of the excessive-force plaintiffs, Jordan Branstetter, won his case in court.

In that case, Branstetter said a corrections officer at a state prison in Hawaii had viciously assaulted him for nearly 20 minutes, punching him in the back of the head as he curled into a fetal position on the floor, then kneeing him in the back, breaking two ribs, and choking him.

The Hawaii Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation did not respond to requests for comment.

Less than a third of the cases reached settlements — far less than is typical for civil suits filed in the outside world. Of the excessive-force settlements made public, two were for more than $1 million, but the typical award was about $9,000. None of those cases involved an admission of wrongdoing. Whether for technical reasons or because they viewed the use of force as necessary, federal courts across the country offered impunity to officers accused of excessive force the vast majority of the time.

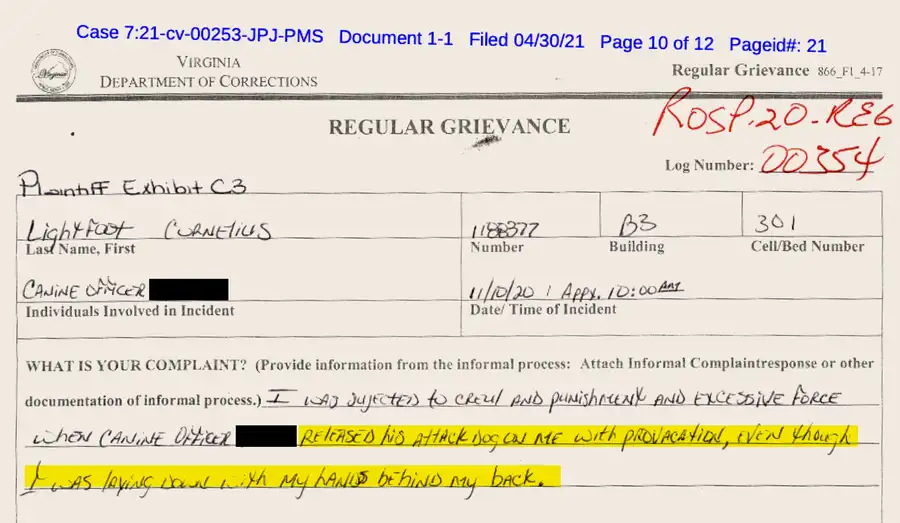

In September 2022, Judge James Jones of the District Court for the Western District of Virginia ruled that officers at Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison were justified in deploying a dog to attack Cornelius Lightfoot. Two officers, thinking Lightfoot had a weapon, tried to frisk him and, when he resisted, tackled him to the ground; a handler then allowed his dog to tear open the flesh of Lightfoot’s thigh. An incident report showed that Lightfoot was unarmed by the time the dog attacked; he said in his complaint that the officers had acted in retaliation, taunting him just before the attack that the dog would get his “grievance-filing ass.”

The officers said they thought Lightfoot had posed “a serious threat to staff safety.” Jones reviewed surveillance footage and determined that Lightfoot was resisting the officers as they tried to subdue him and dismissed the case, ruling that “no reasonable jury could find that any of the defendants used physical force or the canine ‘maliciously and sadistically to cause harm.'”

The UCLA law professor Sharon Dolovich discussed the malicious-and-sadistic standard in a 2022 Harvard Law Review article. “That this standard is intrinsically defendant friendly,” she wrote, “is undeniable.”

Cornelius Lightfoot filed a grievance saying he was attacked by a patrol dog while at Red Onion State Prison in Virginia. He later filed an Eighth Amendment suit.

Jones, and every other judge mentioned in this story, declined to comment on the record for this story or did not respond to queries. Kyle Gibson, a spokesperson for the Virginia Department of Corrections, declined to comment on the Lightfoot case but said that the agency had “zero tolerance for excessive force or abuse” and that violators “are disciplined according to agency operating procedures.”

At about the same time as Jones’ ruling, judges with the 5th Circuit appeals court ruled that five officers at a Texas prison known as Coffield Unit were justified when they pepper-sprayed a prisoner who had refused to leave his cell, then put him in a chokehold and wrestled him to the ground. The prisoner, Robert Byrd, was serving a life sentence for capital murder; as he was splayed under the weight of four officers, a fifth officer smashed his outstretched arm with a riot baton, breaking a bone.

While officers later photographed a wooden shank they said was recovered from Byrd’s cell, an internal prison investigation determined that Byrd was restrained and unarmed when he was struck and that at least one officer, the one wielding the baton, had deployed excessive force. Still, the appeals court decided that even if Byrd was unarmed, he was violently resisting, so force was “obviously necessary.” All the officers had deployed force, Judge Stuart Kyle Duncan wrote in the majority opinion, “in a good-faith effort to maintain or restore discipline.”

Amanda Hernandez, a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, said the video footage of the incident was key to the state’s case because it showed a “‘hostile, combative, utterly noncompliant’ prisoner who was committed to violent resistance.”

“We are to accord prison officials ‘wide-ranging deference,'” Duncan, one of the 5th Circuit judges who heard Byrd’s case, wrote, quoting case precedent. “The Supreme Court has told judges not to micro-manage the force necessary to quell such volatile situations.”

Judges dismissed other cases on technicalities.

In August 2022, D’Andre White, a prisoner at Ionia Correctional Facility in Michigan, filed suit claiming that, earlier that year, he’d been shackled by his hands and feet in a bathroom stall during a court appearance when he asked a guard to uncuff one hand so he could more easily use the toilet. The guard refused, White said, then grew irate at how much time White was taking. White said the guard then grabbed him by the throat, slammed him to the ground, kicked him repeatedly, and dragged him to the court’s holding cell.

Robert Jonker, a judge in the District Court for the Western District of Michigan, ruled against White, finding that he had not fulfilled his prison’s internal grievance process before filing suit, as required by the PLRA.

The Michigan Department of Corrections did not respond to requests for comment.

Two years later, in 2024, Judge Christine O’Hearn of the District Court for the District of New Jersey dismissed the case of Tyrone Jacobs, a federal prisoner who said that four officers had retaliated against him for filing complaints against the prison. He said the officers handcuffed him, pulled him from his cell, and, out of view of surveillance cameras, slammed his head against the wall and dragged his face along the concrete. Jacobs said one officer screamed, “I will fucking kill you.”

Because Jacobs had missed a deadline to appeal his internal prison grievance, O’Hearn decided in favor of the defendants.

A ‘good-faith effort’ to restore discipline

In B-17 sample of excessive-force lawsuits, one facility stood out: California State Prison, Sacramento, popularly known as New Folsom. The vast complex surrounded by steel fences and guard towers was built in the 1980s, just across from the Gothic granite tower of Old Folsom, the site of Johnny Cash’s legendary 1968 live album. The new facility has a reputation for violence. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation data shows corrections officers there deployed force at a far higher rate than any other California prison over the past decade. In 2023, the most recent year for which data is available, New Folsom officers used force — fists, baton strikes, pepper spray, or high-velocity less-lethal ammunition — in nearly 700 documented incidents. That’s nearly twice a day. By comparison, officers at the California City Correctional Facility, a high-security facility in Southern California that was recently decommissioned, used force 192 times — less than four times a week.

Violence by guards at New Folsom sparked three complaints of excessive force in B-17 sample; all of the plaintiffs lost.

Johnny Cash performing at Folsom Prison in 1966. He would record a live album there in 1968.

The allegations contained in the legal complaints, together with evidence from state oversight reports and criminal cases against former officers there, hint at a corrections culture in which casual violence prevails and retaliatory cruelty often goes unchecked.

Terri Hardy, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, emphasized that in each California case mentioned in this story, the department prevailed, and said the department “takes every allegation of employee misconduct seriously.”

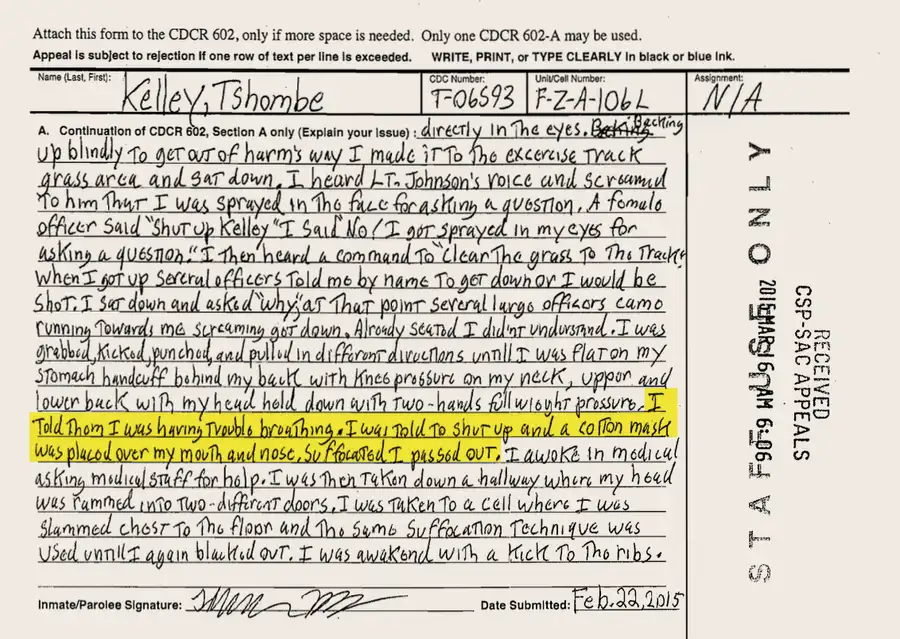

One complaint describes an incident that took place in February 2015, in New Folsom’s C yard, where a man named Tshombe Kelley, who was serving 52 years for murder, approached a group of officers to ask a question. When he and another prisoner didn’t immediately comply with an order to back away and drop to the ground, incident reports show, officers swiftly reacted. One officer, who said he saw Kelley clench a fist, blasted him in the face with pepper spray. Kelley said he reeled back and stumbled to the ground; officers said he again failed to comply with an order to lie flat. Two other officers then deployed physical force, an incident report shows; Kelley said they punched him, kicked him, and dragged him in the dirt. Transcribed surveillance video describes the officers wrestling Kelley into handcuffs and pinning him down with their knees on his shoulder and back, as he pushed against their combined weight.

An officer heard him plead, “I can’t breathe.”

Instead of easing up, officers deployed a spit mask, a cotton bag that covers the face and head. Blinded and panicked, his throat burning from the pepper spray, Kelley later said, he lost consciousness.

A California prisoner named Tshombe Kelley said officers used so much pressure on his neck and back that he lost consciousness. He lost his excessive-force claim when a federal judge ruled that the officers’ use of force had not been malicious and sadistic.

Kelley sued and lost. Officers said in court filings that they feared Kelley and another prisoner might attack them; they said Kelley had refused a direct order to hit the ground and resisted their attempts to restrain him, and only one recalled hearing Kelley say he couldn’t breathe. Surveillance video showed that as Kelley was pinned down — and struggling to breathe — he arched his back and thrashed his legs. Carolyn Delaney, a magistrate judge with the District Court for the Eastern District of California, found that the officers’ use of force was necessary to combat Kelley’s “ongoing resistance.”

Judges also sided with guards who injured prisoners they didn’t perceive to be resisting.

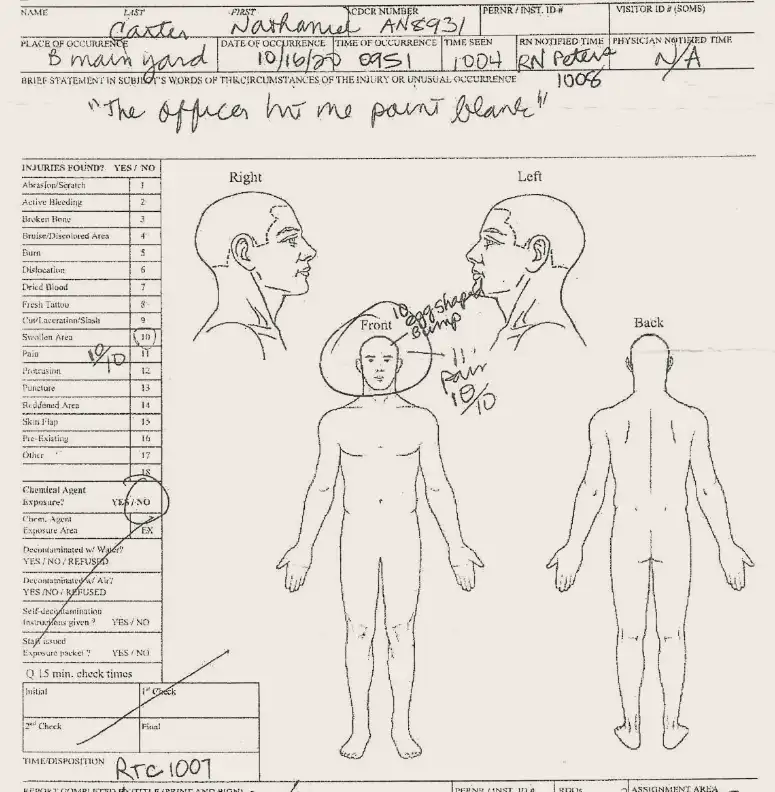

In October 2020, less than a year after Kelley’s case was dismissed, a prisoner named Nathanael Carter Jr. noticed a fight erupt in the New Folsom B yard, according to his civil suit. Guards ordered all prisoners to the ground. Carter immediately complied, dropping to his stomach, arms spread-eagled. From the guard tower, an officer fired two less-lethal rounds from his state-issued 40 mm launcher into the crowded yard, according to multiple incident reports. Both shots missed the men fighting. But one round smashed into Carter’s skull, leaving a hematoma the size of an egg and triggering migraines, blackouts, and memory loss.

Like Kelley, Carter lost his case. He’d argued in court filings that he was an innocent bystander who was shot despite “getting on the ground following instructions.” The guard said he’d hit Carter by accident, and Dennis Cota, an Eastern District magistrate judge, ruled that the use of force related to “the prison’s legitimate penological interest in maintaining security and order.”

While trying to break up a fight, an officer at New Folsom prison in California shot a bystander, Nathanael Carter Jr., in the head with a less-lethal round.

In more than a dozen cases in B-17 sample, judges found that the question of whether a use of force was malicious and sadistic was immaterial, as long as officers were doing their job.

Federal courts grant broad protections to law-enforcement officers for actions taken “under the color of law” — in the line of duty.

That’s how one California prisoner’s case failed before the District Court for the Eastern District of California. In his complaint, the prisoner said that six corrections officers at a federal prison in Atwater in April 2021 threw him to the ground, handcuffed him, and slammed his head against the wall before dragging him to a holding cell where they physically and sexually assaulted him while calling him racist slurs.

Magistrate Judge Stanley Boone recommended dismissal of the case, finding that any remedy the court might impose “risks interference with prison administration.” District Judge Jennifer Thurston agreed and dismissed the case.

Ben O’Cone, a spokesperson for the Federal Bureau of Prisons, did not address the Atwater case but said the agency “does not tolerate excessive use of force” and thoroughly investigates all allegations of employee misconduct.

Cases against corrections officers run into another set of challenges under the doctrine of “qualified immunity.” Unless a court has previously found that a particular use of force constituted a constitutional violation, a defendant is given the benefit of the doubt under the doctrine. The Supreme Court standard, established in 1967 and refined in 1982, shields public officials from civil liability when they’re legitimately acting in the line of duty. The standard has drawn national attention as an obstacle to police accountability. In prisons, B-17has found, qualified immunity has also protected corrections officers who have been accused of excessive force.

That’s how things played out in court in the wake of a December 2016 incident at the Darrington Unit, now called Memorial Unit, in East Texas. That day, a prisoner named Marquieth Jackson threw water at a corrections officer passing by his solitary-confinement cell. Incensed, the officer brandished his pepper spray and threatened Jackson. He then spun and blasted a prisoner in a nearby cell in the face at point-blank range.

Why he did so is contested: The officer, Tajudeen Alamu, said that after he was doused with water, he ran for cover by the cell of the other prisoner, Prince McCoy Sr. Alamu said that McCoy threw something that hit him in the face — court documents later identified it as a wad of toilet paper — and that his mind then “went blank” and he reacted instinctively. McCoy denied throwing anything and said Alamu attacked him in anger “for no reason at all.”

Alamu did not respond to requests for comment by phone and mail.

After losing at the district court level, McCoy appealed and got a rare finding from the judges of the 5th Circuit. They decided that Alamu had been “malicious and sadistic” in his use of force, in violation of the Eighth Amendment. But after finding that no previous case in the 5th Circuit had established that pepper spraying a man confined in his cell constituted excessive force, they granted Alamu qualified immunity.

“How could any guard not know that an unprovoked use of pepper spray is unlawful?” Gregg Costa, one of the appeals court judges, wrote in a furious dissent. “Yet the majority concludes it would have been reasonable for a guard to think the law allowed him to gratuitously blind an inmate.”

The other judges’ reading of the qualified-immunity standard, Costa wrote, “ensures vindication of the most egregious constitutional violations.”

McCoy appealed, and the case made it to a jury, which again found for the defendant. But the jury disagreed with the 5th Circuit on one critical point: The pepper-spray deployment, they found, had not been malicious and sadistic.

A culture of silence

This pattern of rejection by the courts is especially devastating to prisoners, given how hard it is for them to file suit in the first place.

For nearly 30 years, thanks to the PLRA, any prisoner who wants to file an excessive-force claim has to first file an internal grievance — a petition to prison administrators to address violations committed by their staff. But it can be dangerous for prisoners to report an incident involving the very officers who control every aspect of their daily lives. The cases B-17 reviewed contain multiple claims of retaliation against prisoners who decide to complain.

One complaint, filed by a New Folsom prisoner named Christopher Elliott, offers a window into the ordeal prisoners often face when they seek redress.

In 2023, corrections officers at California’s New Folsom Prison used force — fists, baton strikes, pepper spray, or ammunition — nearly twice a day.

In January 2021, Elliott tried to raise an excessive-force complaint, filing a grievance that said a corrections officer had shoved him onto the concrete floor of his cell and jumped on him while his legs were shackled and his arms were cuffed behind his back. Medical records show a laceration on his left hand, which he said got pinned behind him in metal cuffs, spattering blood across the floor.

After Elliott filed the grievance, he said in a court filing, the corrections officer returned to his cell to issue a threat: If Elliott didn’t stop pursuing the grievance, the officer would force Elliott to perform oral sex on him — and order Elliott killed.

When asked about allegations of violent retaliation by prison staff, Hardy, the California corrections spokesperson, said the department had “fundamentally reformed” its approach to investigating allegations of staff misconduct and had deployed body cameras and audio surveillance to “create an environment in which incarcerated and supervised persons are comfortable raising concerns without fear of retaliation.”

Akiva Israel, a transgender woman who was incarcerated at another California men’s prison, Mule Creek, filed an internal grievance in April 2021 accusing an officer named J. Padilla of threatening to sexually assault her. She said other gay and transgender prisoners immediately warned her to be careful: Reporting the officer might invite even worse consequences.

Israel later filed a civil complaint saying that a week after she submitted the internal grievance, officers handcuffed her and brought her to a prison administrator’s office where they hurled transphobic and homophobic slurs and again threatened her with sexual violence. “You fuck with Padilla,” she quoted one officer saying, “You fuck with me.”

She said the officers then marched her to solitary, stripped her naked, threw her to the floor, and kicked her in the head. They then yanked her off the ground, she said, suspending her by the metal cuffs, causing “excruciating agony,” and slammed her to the concrete floor.

Kimberly Mueller, a judge with the District Court for the Eastern District of California, dismissed Israel’s case without prejudice on a technicality. Handling her case without an attorney, she had missed a deadline to file an amended complaint while being treated for breast cancer.

In Elliott’s case, Kendall Newman, a magistrate judge in the same court, also recommended dismissal on technicalities: Elliott might have a case, Newman said, but he had not signed his complaint filing and his claims of retaliation were unsupported by evidence.

It has become so rare for the courts to find constitutional violations that the wins send shock waves through prison communities. On October 17, 2022, William Shubb, a senior judge in the Eastern District, sentenced a former New Folsom guard, Arturo Pacheco, to 12 years in prison for knocking the legs out from under a handcuffed 65-year-old prisoner who landed face-first on a concrete walkway, breaking his jaw. The prisoner, Ronnie Price, suffered a pulmonary embolism and died two days later.

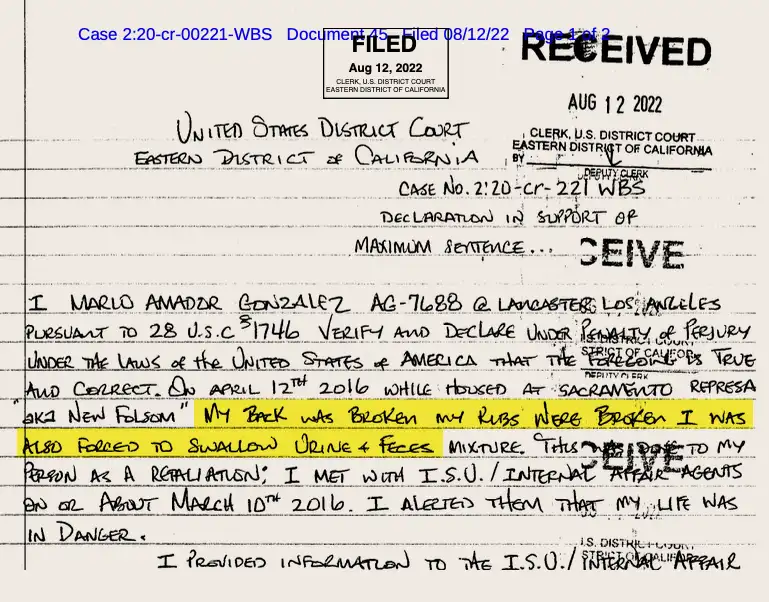

In the lead-up to Pacheco’s sentencing, a New Folsom prisoner named Mario Gonzalez fired off an urgent letter to Shubb, saying Pacheco and another indicted officer “know more than what they’ve shared.” He said many more staff there should be prosecuted, including corrections officers who he said “cuff us and beat us” and lieutenants who he said had lied in incident reports to cover up excessive force.

Gonzalez, outside the residential treatment program where he lives in Costa Mesa, California. In his lawsuit, he said officers at New Folsom were engaged in “illegal beatings of fellow inmates.”

In an earlier civil suit, Gonzalez said he’d reported to his prison psychologist that a group of officers was committing “illegal beatings of fellow inmates” and that he feared for his safety. Soon after, he wrote, four officers cornered him in his cell: One put Gonzalez, who then used a walker, into a headlock, wrenching his spine backward until he feared it would snap. Three others kicked him in the ribs, torso, back, and groin, then scooped urine and feces into his mouth.

“My back was broken. My ribs were broken,” Gonzalez wrote to Shubb, injuries that he had documented in his civil suit and in prison grievances. “I have night terrors at least 4-5 times a week. I also cannot get that piss and shit taste out of my mouth.” He said he reported the incident but believed no internal investigation had taken place. His case was dismissed repeatedly over six years while he was in prison, most of the time without a lawyer. He wrote to Cota, the Eastern District magistrate judge, alleging that officers were retaliating against him for being outspoken by locking him in solitary confinement and inciting fellow prisoners to attack him.

“I pray you please take action cause my life is endangered,” he wrote in one letter.

Still, his complaint languished. Only after Gonzalez got a new lawyer and was released from prison in the fall of 2023 did Cota allow his case to continue. (The case remains ongoing.)

The California state prison system has been under official scrutiny for decades, springing from a 1995 decision by a federal judge finding a pattern of egregious violence perpetrated by guards at Pelican Bay State Prison, some 380 miles northwest of New Folsom, in violation of the Eighth Amendment. California prison officials, the judges found, “permitted and condoned a pattern of using excessive force, all in conscious disregard of the serious harm that these practices inflict.”

It remains the only case decided under the malicious-and-sadistic standard to spark significant prison reforms in the state.

In a letter to a federal judge, William Shubb, Gonzalez said his back and ribs were broken and he was forced to swallow urine and feces in an act of retaliation by guards.

The court mandated a suite of new oversight mechanisms, including the appointment of a special master and a new use-of-force action plan.

Nearly a decade later, the special master issued a scathing evaluation: California prison officials had deliberately misled the court by filing false or misleading reports. The report found that administrators had endorsed a “code of silence” — an informal but aggressively policed policy under which corrections officers refuse to report misconduct to avoid being labeled “a rat.”

The special master found California’s entire system for investigating and disciplining officers accused of excessive force was “broken to the core.” The court ordered a new plan, which included direct oversight and annual reports from the state’s inspector general.

The special master’s mandate has long since expired. Yet the inspector general’s annual reports continue to identify severe deficiencies in how California prisons deploy and investigate the use of force.

Gonzalez already used a walker in 2016 when, he said, officers put him into a headlock and wrenched his spine backward until he feared it would snap.

In 2023, the most recent year examined, the inspector general reviewed 730 use-of-force incidents and identified 225 that appeared to involve staff misconduct, including 82 incidents where staff may have deployed excessive force. Prison officials initially failed to refer nearly half of those 225 incidents to internal affairs for investigation, including incidents involving the potential use of excessive force and those involving the potential withholding of medical treatment or failure to follow protocol.

The inspector general found that officers repeatedly failed to turn on their body cameras, sometimes wrote misleading or blatantly untrue use-of-force incident reports, or failed to report deployments of force at all. In the vast majority of cases, supervisors rubber-stamped the use of force as acceptable, often without interviewing the prisoner in question or reviewing all of the available video evidence. Even after the inspector general’s investigators identified cases that appeared to involve excessive force, they found that prison officials sometimes declined to open internal affairs investigations into the officers involved.

These patterns had been long documented. In each of the five years preceding 2023, the inspector general found that California prison staff appeared to have violated use-of-force policies in at least 40% of the hundreds of incidents the office reviewed. Each year, the office also found significant deficiencies in how managers investigated use-of-force incidents — and found that supervisors regularly declined to take action against officers who deployed “unreasonable force.”

If the courts were expected to provide a backstop, they failed.

Over the same five years in B-17 sample, no federal judge found for the plaintiff in a single excessive-force claim filed by a California prisoner.