I quit my finance job to pursue my dream of writing comics. I used a pitch deck to convince my parents it was a good idea.

Brandon Chen is the writer behind series like “Just A Goblin” and “God Game.”

This as-told-to essay is based on a conversation with Brandon Chen, a 27-year-old webcomic author from New York City. It has been edited for length and clarity.

I was 7 or 8 when I discovered comics.

My mom got me this manga from the library called “Dragon Ball.” It was the first time I’d read a series that was not just words. The narrative concepts and beautiful drawings got me hooked, and I started to want to draw and do that kind of work myself.

In elementary school, I used to create a weekly manga magazine for myself and try to sell it to kids on the playground for quarters. No one was biting really, but it was just something I would do. That’s how I started getting into the manga space.

Writing and drawing involve very different skill sets, and it’s hard to improve both simultaneously. You’re doing one or the other; there’s an opportunity cost there. I felt I had to make a decision.

I was 14, and I was like, “I’m going to decide my future right here, right now, kind of like an anime protagonist, and bet it all on a coin flip.” If it’s heads, I’m a writer; if it’s tails, I’m an artist. The coin landed on heads. I had an art Instagram at the time, and I deleted the whole thing and went all in on writing.

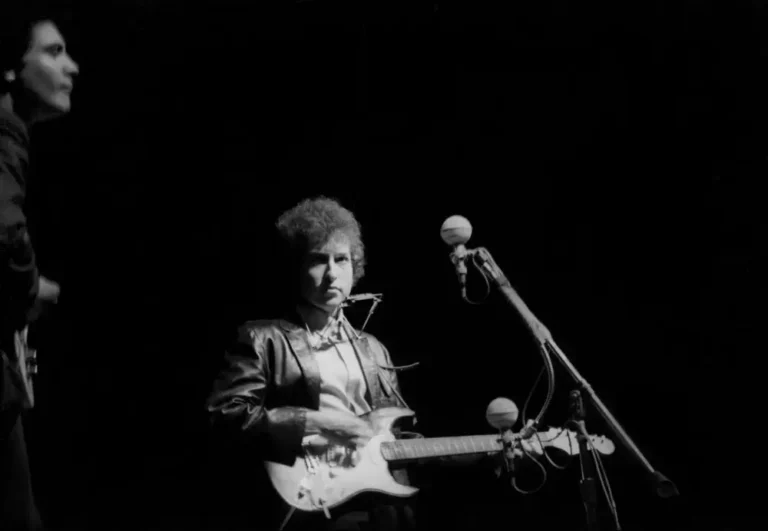

Brandon Chen at New York Comic Con.

I published my first novel when I was 17

I started working on writing my first novel when I was 14. It was pretty heavily inspired by the manga series “Naruto,” which was a big thing around that time.

I focused on novels, not manga, at that point because I had quit drawing. I didn’t understand how the whole comics business works, and working with an artist, until later on in my career.

I was chronically online as a teenager, so I promoted my work on Wattpad. I was driving a lot of traffic from Instagram to my Wattpad, and it got 100,000 reads, which at the time for me was pretty great. I was like, “Wow, I’m getting a lot of feedback.” I went ahead and finished that novel, packaged it, and self-published it when I was 17.

I think the hardest part about writing novels or doing any creative project is that the first time you do it, it’s super hard. The second time you do it, you know all the pain points and the process: how to work with an editor, how to hire an illustrator, all that stuff.

From ages 17 to 20, I put out a project every single year, whether it was comics or novels. I stopped releasing novels around 21 or 22 because I was shifting back into visual storytelling.

I was at NYU studying economics and computer science at that time, and like a lot of college students, I felt I had a lot of freedom. I was an OK student sometimes, but I was also the type of student — and I don’t encourage people to do this! — that would always learn better outside the classroom.

I’d go to class a few times, and then sometimes skip class and use that time to write and study instead. Some people were partying more than me probably, but a lot of what I used to do in my free time was writing.

When COVID hit, I kept pursuing writing

After I graduated from NYU in 2019, I took a consulting job at KPMG, but I was entering my quarter-life crisis for sure.

Those first few months out of college were rough for me because, before COVID hit and we were all stuck inside, I was working 60 to 70 hours a week in an office. You get off work, the next thing you do is eat, maybe you work out, then you sleep, and then repeat. Your weekends are like, “Oh man, I just need to rot to cope with that rough week.”

It was actually COVID that allowed me to make this career change, because I had more time to myself.

The free time I had from avoiding commutes and avoiding seeing my friends enabled me to start writing again. I would put in a total of maybe a hundred hours a week: If it was 60 hours that I was working that week, I’d put another 40 into writing.

I wasn’t sleeping that much, but I was grinding a lot to try to make the dream happen.

A panel from the Webtoon series “Just A Goblin.”

My comic “Icarus Rising” was the one that kind of jumpstarted everything in 2020.

The artist and I did an entry to Shōnen Jump Tezuka, a manga contest in Japan. I was posting about my process on TikTok, and a lot of those videos went viral. “Icarus Rising” was also going viral, and it enabled me to get my first serialization deal for “God Game,” which is still running.

From there, I was able to connect with Webtoon using my portfolio and get “Just A Goblin” off the ground. That was just the start of my partnership with Webtoon. We have a bunch of other series, like “Samurai no Tora” and “Angel Wings,” that we’re doing with them now.

I convinced my parents that my webcomic career was sustainable

I finally quit my finance job in May 2021.

At some point, I realized I was making the same, if not more, than my finance salary from writing part-time. But my parents are very traditional Chinese — there was concern over “Hey, is this sustainable?”

I had to do the classic consulting thing where I market, pitch, and basically build a PowerPoint deck to assure them: “Mom, Dad, here are the projections. If I don’t hit these projections over the next five years, I will go back to my job that I promised I would do after college to make back that college tuition.”

I was just convincing them that I wouldn’t be out of money and that I’d be OK. As soon as they saw the numbers, it was actually not super hard to convince them. And clearly, it’s worked out.

The catalyst for all this, in the quarter-life crisis mode, was definitely when the mangaka Kentaro Miura, who did “Berserk,” died in 2021. He was in his 50s. My thought was: “What if I turn 40 and I’m still doing this finance job, and I never took a chance on myself and then I died one day? What a tragedy. Why don’t I just take my risk now?” And that’s when I took a jump, and then I had to convince my parents.

My entire life they’ve known that this is my calling. They see everything I’m doing and my passion. The question for them always was, “When is he going to do it?”