I’m a British expat who worked in China’s brutal 996 tech culture. I’m relieved they laid me off.

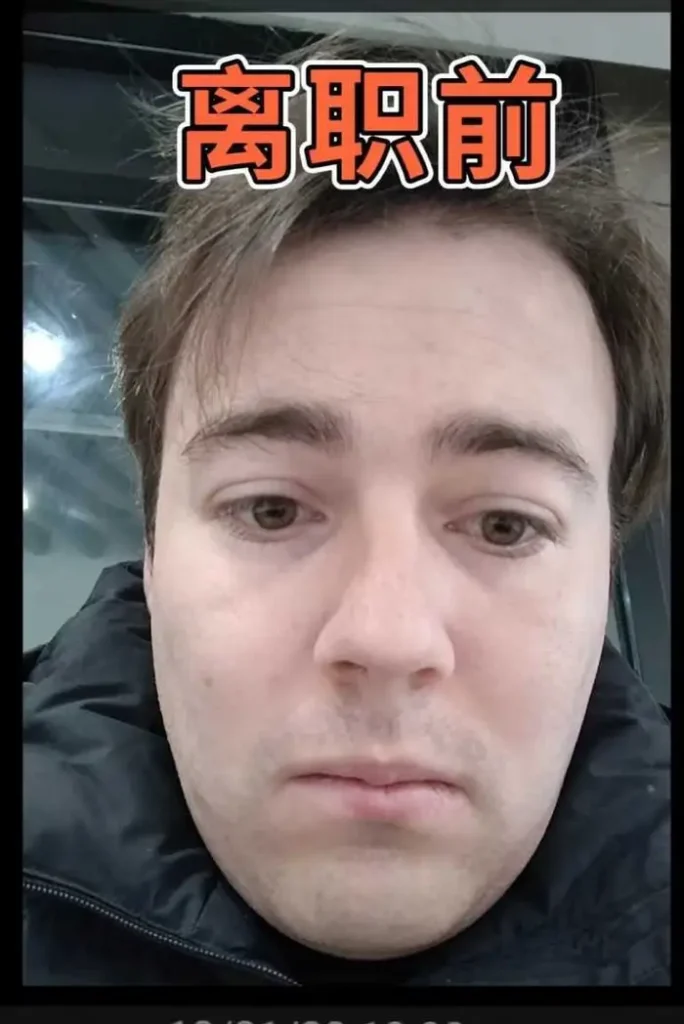

Forsdike said the long work hours under China’s 996 culture took a toll on his mental and physical health.

When I first learned I’d be subject to China’s infamous 996 hours, I was actually excited.

At that point, I’d worked for nearly two years in Guangzhou as an English-Chinese interpreter at a local tech giant.

But my passion was in game design, so it was my dream come true when my employer offered me a development role in January 2024.

Human resources straight-up told me that my hours would increase drastically.

As an interpreter, I’d grown accustomed to a knock-off-at-seven office life. Developers were instead expected to work from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day, six days a week.

That wasn’t what our contracts said, but it was understood as the norm.

At the time, being put on 996 felt like I was being recognized. I had this idea that those work hours meant I was on a serious, valuable team and that my productivity mattered.

I soon realized how naive I was.

Forsdike studied Chinese for about six years as he was attending university, before moving to Guangzhou to work.

Life didn’t exist outside 996

My 996 life didn’t start immediately; I’d just gotten married and asked my manager if I could leave the office early on some days and not work every Saturday.

He agreed. As long as I could get the job done, he said.

But eventually, the work began piling up. I’d have to come in on the odd Saturday or Sunday. On some days, I started leaving work at midnight.

In a few months, my 996 schedule was in full swing. I spent my waking hours either leaving the office, being in the office, or getting to the office.

Working weekends wasn’t going to get me a pat on my shoulder. Even on Sundays, I found out it was normal to see a third of the office around.

The worst month was April, when my team was under pressure to meet a deadline. Western game developers use the term “crunch” to describe grinding unpaid overtime before a big release.

Normal 996 already felt like “crunch,” so this was “crunch” on steroids. There was a period when I worked 12- to 14-hour shifts for three weeks straight — around 20 overtime days in the office without any rest.

“My face shape is like a potato,” Forsdike wrote in a social media post on a day he worked overtime.

I would typically reach the office just before 10 a.m. for breakfast — where all meals were subsidized at the company canteen. Then, I’d work until 12:30 p.m. when it was time for lunch.

We enjoyed the privilege of a 90-minute lunch break, during which I could grab a coffee with office friends and vent for an hour or so. I think that was one of the reasons I survived the 996 routine.

Then we’d work again before grabbing a quick dinner, after which we’d plow through the rest of the night. This wasn’t really treated like overtime — my bosses regularly scheduled 9 p.m. meetings.

I’d get home after midnight, take a shower, and head straight to bed. Then I’d get up and do it again.

Life outside work was nonexistent. I was barely getting any face time with my wife. I’d stopped playing tennis, which is one of my favorite hobbies, and I couldn’t work out. Every meal I ate was in the office canteen.

Forsdike said he realized he’d been spending almost no time with his newlywed wife after working 996.

I started to realize that my health took a hit. I was losing muscle and gaining weight. It was becoming unsustainable, but I just prayed that the pressure might lighten up.

This was going to be my life

A continual blow was that we never saw the senior managers who made the decisions keeping us in the office. They’d assign deadlines from above, and our team leaders were powerless to negotiate.

But what really hit my morale was the understanding that this was a long-haul expectation.

Plenty of people work insane hours back home in the UK. Yet there’s typically light at the end of the tunnel, like a job placement or a promotion.

In 996, these hours are the minimum. Everyone, from my manager to my colleagues to my friends in other teams, knows this work life is never-ending and demanding, yet they all seem resigned to it.

With 996 as the industry standard, my colleagues were afraid that if they switched companies, they’d end up in a tougher role.

I finally got a break in May. Labor Day is one of China’s biggest “Golden Week” holidays, and I’d negotiated a longer period of leave as a condition for switching to my new role.

When I returned, I found out that most of my team, including myself, had been laid off. Our project was essentially finished, but the company decided to roll back to an earlier stage of development in our game.

I was disappointed, mostly because I’d just worked crazy hours for this firm. But a wave of relief swept over me, too.

996 made me realize that I’d been missing so much in life outside work, and getting laid off hit the reset button for me.

Forsdike has been spending time off with his wife, who is Chinese, in Harbin, which is famed for its ice sculptures.

Senior managers need to know that the 996 mindset is just outdated. It doesn’t make your teams more productive because it crushes morale, and tired teams make more mistakes.

After leaving the office for good at the end of my 28-day notice in June, I’ve been spending some time away from work with my wife in the frosty city of Harbin.

My dream is still to make games in China, but I’m not sure if any company could ever entice me to work 996 hours again. There’s just too much I’d lose.