Inside the Billionaire BunkerIt’s America’s wealthiest town. Approach at your own peril.

As my boat cruises toward the private island city of Indian Creek Village — better known as the Billionaire Bunker — I’m hoping my trip doesn’t end in an arrest.

It’s a hot morning on South Florida’s Biscayne Bay, and I’ve convinced two local tour boat captains to pilot me around the perimeter of what is quite possibly the wealthiest and most heavily defended town in America. I’m not entirely clear on the rules about boating near the island, which lies just across the bay from Miami, and neither are my captains — they’re both in their first weeks on the job. What I do know is that Indian Creek employs a new all-seeing security system and a small navy of police officers who frequently stop and ticket boats that venture too close to the island’s manicured shore.

As we near the northwestern side of the island, I spot the bright red steel beams of “La Petite Clef,” the Mark di Suvero sculpture that towers 20 feet over the front lawn of the car magnate Norman Braman’s mansion. We glide past a modern palace hidden behind a dense cluster of palm trees, purchased for $50 million in 2019 by a mysterious LLC linked to the emir of Qatar. On the southwestern shore, we come upon the island’s most sought-after mansions. This is where the elite of the elite live: Tom Brady, Carl Icahn, and the neighborhood’s most recent arrival, Jeff Bezos. The wealth here is staggering — 25,000-square-foot mansions with ivy-strewn stucco walls, fronted by sprawling lawns and sleek yachts. Today, almost all the mansions appear to be empty.

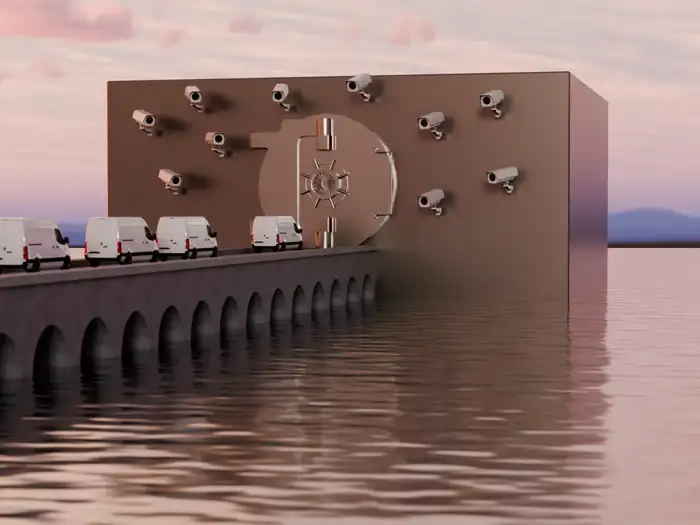

As we get closer to the shore, I start to notice the cameras.

Their beady eyes are everywhere. Some are mounted on poles along the seawall. Others peek out from hedges. Many are connected to an inconspicuous white box — an Israeli-designed radar system capable of detecting passersby, in low visibility, from half a mile away.

There is no way for a person to set foot on Indian Creek without the express permission of one of its 89 residents or a member of its ultra exclusive country club, which reportedly costs $500,000 to join. Because the town’s government serves such an ultra wealthy subset of the population, things like public parks and social programs are practically nonexistent. Instead, the lion’s share of Indian Creek’s budget goes to its police department — which keeps watch on the island’s sole entrance and patrols the perimeter 24/7. Through federal funds, the town has also amassed a panoply of other security measures that would make Bezos’ Ring cameras blush.

“The wealthier you become, the more you want perfect security,” says Setha Low, the director of the Public Space Research Group, a center at the City University of New York that focuses on the access and control of everything from city parks to gated communities. “And that produces an industry making a lot of money off of people’s fear.” Much like the military-industrial complex, she says, “there’s a security-industrial complex — this entire sector of our economy being fed by people wanting this kind of security.”

I’m relieved when we pull away before running into an Indian Creek police patrol. But there’s no doubt we’ve been seen. In an increasingly atomized age, the Billionaire Bunker is an increasingly insular and secure enclave. If you want to live in a part of America that no outsiders can set foot in, Indian Creek is the most gated community in a country of gates.

Dredged from the Tiffany-blue waters of Biscayne Bay in 1928, Indian Creek was incorporated in 1939 under a now defunct Florida law that allowed groups of more than 25 people to form their own municipalities. Designed to re-create the English countryside, the 300-acre island is more than 80% golf course, encircled by a single road and 30 or so mansions. The village was initially envisioned as a refuge for wealthy white gentiles. Early residents included William Henry Hoover, of vacuum fame, and Frank Woolworth, the eponymous founder of the department-store chain. Back then, residents conspired to keep Jewish homebuyers out by running their electric services exclusively through the formally segregated Indian Creek Country Club.

An Israeli-designed radar system encircling the island can detect passersby, in low visibility, from half a mile away.

That system of de facto segregation no longer exists, but Indian Creek remains fixated on keeping certain people out. “The security is very different than how it used to be,” says Gerardo Vildostegui, who grew up in the neighboring town of Surfside, a middle-class community that shares a two-lane bridge with Indian Creek. A member of Surfside’s town council, Vildostegui recalls a time in the early ’90s when he could bring his college friends to Indian Creek’s gate and get permission from the police to give them a tour of the island. Now if he approaches the bridge, the cops start flashing their lights and order him to back away.

In the 1980s, the island’s police force — whose motto is “protecting and serving America’s most exclusive municipality” — was made up of 11 people. Recent town documents show they employ 19, one for every five residents. That’s compared with a national average of about 2.4 cops per 1,000 residents. If New York City had the same officer-to-citizen ratio as Indian Creek, it would employ more than 1.5 million cops. Because Indian Creek’s denizens are jet-setting billionaires with homes all over the world, there are likely many days of the year when police officers actually outnumber the island’s residents.

If New York City had the same officer-to-citizen ratio as Indian Creek, it would employ more than 1.5 million cops.

Often described as “butlers with badges,” the Indian Creek police force is unlike most of its counterparts. For starters, it’s nonunion. The town government quashed a union drive in the 1980s, firing a lead organizer accused of taking gasoline from a town tank. And rather than responding to calls from citizens in need, the police spend an estimated 97% of their time on security work, like patrolling the island’s perimeter in three high-speed police boats and manning the access command center by the bridge. The force’s recruitment materials say officers have “extremely high levels of training in areas such as weapons, defensive tactics, and tactical operations” and are trained to use fully automatic firearms. All told, the town spent $4.1 million — a whopping 74% of its budget — on public safety in fiscal year 2023.

In 2011, the town installed new cameras by the entrance gate that allow police to simultaneously view a visitor’s face, pull up their driver’s license, and read their license plate. Indian Creek also narrowed the gate’s opening to create what it called “a greater sense of exclusivity.” In 2012 the town replaced the tinted bullet-resistant glass in the access command center, and in 2013 it added a fence to keep pedestrians out. Such investments are generally lauded by residents, who often push the town council for more stringent security measures. “Safety is our No. 1,” Irma Braman, Norman’s wife, said at one meeting. “It should be everyone’s No. 1.”

Whatever crimes the island’s residents may be committing, they aren’t doing it on the island. Many years, not a single offense is reported to the Indian Creek police. Instead, the cops have their hands full fending off the curious boaters who try to land on the beach near the golf course. “The police are being run ragged right now,” Mayor Bernard Klepach — who is also the CEO of the world’s largest in-flight duty-free company — said at a council meeting in 2020, referring not to a crime wave but to recent incursions by beachgoers. “We need something quickly.”

That year, Indian Creek began its most substantial security upgrade in decades — a high-tech radar fence encircling the island. According to public records, the system features 10 thermal cameras and 17 radar sensors mounted at nine locations along the island’s perimeter, in addition to 30 traditional cameras. The radar sensors overlap, creating what the records call a “geofence” that can detect anything that comes within a half-mile of the shore. The project cost about $1.6 million — equal to about a quarter of the village’s annual budget.

The radars were built by Magos, an Israeli company whose founders worked with military radar technology before shifting their focus to private security. Its website says Magos radar systems are generally used in data centers, oil and gas facilities, and solar farms. “Radar works extremely well in wide-open spaces,” says Mike Bullman, who runs Safe Security Solutions, a perimeter-security company that has installed Magos radars around large country estates in the United Kingdom. But he and several other security professionals I spoke with had never heard of one being installed around an entire town.

The Indian Creek radar can detect objects on the water and use artificial intelligence to classify them according to the risk they pose. When a potential threat is detected, the system automatically moves a thermal camera to track it. Police officers at the station can watch a live feed on a software called “Octopus,” and dispatch a patrol boat to investigate.

In 2014, the estimated net worth of the island’s 86 residents was $37 billion. Bezos added $199 billion.

Justin Ross, who’s been running tours of the Biscayne Bay for several years, first noticed the perimeter-security system while boating past the island one evening in 2022. A red light from the shore appeared to latch on to his boat. “I could see it moving,” he recalls. “I was like, oh wow, it’s following me.”

With the new security system, the Indian Creek police appear to have turbocharged their enforcement of regulations in the surrounding waters. In 2019, the department issued 211 traffic and marine citations. In 2022, the first year the radar system was fully operational, the number of citations soared to 1,600.

“Every time I go past Indian Creek, I run into a marine patrol guy,” Ross says. He knows of plenty of boaters who have been ticketed, generally for creating a wake too close to the shore. Passing by the island earlier this year, Ross triggered the attention of an Indian Creek Police patrol. The officer hit him with a $140 ticket for not having the correct safety equipment on board. The Indian Creek police department did not respond to my inquiries.

Residents, for their part, have been enthusiastic about the new system, and several granted easements to allow the tech to be mounted on their property. One key selling point for the ultra wealthy townies: The cameras would never be pointed inward. Only outsiders would be targeted by the high-tech system. “I think the security is great and have been happy with what has been implemented,” Gail Golden, the wife of Carl Icahn, tells me. “Nothing further to add.”

In August 2023, about a year after the perimeter system was installed, Indian Creek residents learned that they had a new neighbor. Jeff Bezos, the world’s second-richest man, had spent $68 million on a waterfront mansion, quickly followed by the purchase of an abutting property worth $79 million. Then, last April, he completed a billionaire’s hat trick, grabbing a $90 million mansion from Javier Holtz, the retired chairman and CEO of Marquis Bank. The Amazon tycoon got to work, applying to build a pickleball court in one of his yards and making plans to tear down two of the dwellings to construct one supermansion.

Bezos’ arrival catapulted the wealth of Indian Creek into a new stratosphere. In 2014, the entire net worth of the island’s 86 residents was estimated at $37 billion. Bezos added $199 billion. The total value of property on the island is approaching $1 billion and seems poised to climb.

“People’s price expectations just jumped drastically,” says Marko Gojanovic, a real-estate agent who has shown several houses on the island. Prices have more than doubled since the start of the pandemic and have increased by at least another 20% since the first Bezos deal. Gojanovic says he’s been asking as much as $150 million for certain properties.

For real-estate agents, Gojanovic says, “access to Indian Creek is almost like gold.” In off-market transactions like the Bezos sales, two or three brokers can find themselves pitching the same property. Agents are expected to keep transactions private, and Gojanovic says nondisclosure agreements are common. The true owners of several Indian Creek properties remain undisclosed, including the buyer of a $65 million property purchased this May.

Dina Goldentayer, who served as the broker for one of the Bezos properties, says security has become a major selling point for prospective buyers. “These people are buying a secure lifestyle as much as they’re buying a big house,” she says.

In recent years, the island, which has long served as a haven for the elite, has become even more exclusive. Vildostegui, the Surfside town council member, says Island Creek residents used to feel more like local celebrities — guys like Don Shula, the coach of the Miami Dolphins, who you might run into at church. Now, Vildostegui says, the island has become “a spot on the international billionaire circuit.”

The new arrivals have triggered a bit of a building boom, with several projects now under construction. When I visit the entrance on a Tuesday afternoon, I count about 30 vehicles entering and exiting in less than 10 minutes — the Teslas and BMWs of the residents and country-club members mixed in with the pickups, vans, and Toyotas of construction workers. A sign by the entrance gate reads “No Trespassing: Private Island,” and a black police SUV idles nearby.

Indian Creek reflects the growing rise of the security-industrial complex, a burgeoning field aimed at assuaging the anxieties of the superwealthy.

Despite the Billionaire Bunker’s fixation on remaining insular, it tends to encroach on the outside world. With on-island parking limited to construction supervisors, crews working on Indian Creek mansions sometimes park along a quiet Surfside street near the bridge. Properties in the neighborhood are also being bought up by opaquely named LLCs tied to Indian Creek residents. Julio Iglesias, a longtime Indian Creek homeowner, is particularly invested in Surfside, controlling through several LLCs at least nine properties within a few blocks of the entrance.

The sprawl into Surfside became a flashpoint in the late 1990s, when Indian Creek began building a new police and government complex on the other side of the bridge. Some Surfsiders felt the station would change the character of their neighborhood, and the conflict grew petty, bringing long-simmering class tension to the surface. Town officials snubbed each other at community meetings and filed competing lawsuits. “We used to tease each other that, for them, Surfside was spelled with an E instead of a U,” says Tim Will, who served as a Surfside commissioner during the spat. “They don’t interact with us unless you’re cutting their lawns or building their piers.”

Will was particularly bothered by the bridge connecting the two towns, which receives public money for repair projects but which the public is forbidden from crossing. Actually, Indian Creek often makes use of public funds to maintain its privacy — security projects like the radar system are almost always funded via a federal forfeiture fund.

Indian Creek eventually won the turf war, and the new police station was built. Tensions with Surfside seem to have cooled, but the questions of public funding and public access remain. The bridge received $875,000 in government grants in 2008, and last November the town requested another $400,000 for repairs. But when I visit the police station at the bridge and ask if I can walk across, I’m barred from entering.

Indian Creek’s growing wealth and security mirror trends among the global superrich. Over the past four years, billionaire wealth has grown by 88%. In April, America’s 806 billionaires boasted a net worth of $5.8 trillion, greater than the annual GDPs of Japan, Germany, and India — and more wealth than the bottom half of America. Miami is frequently said to be the US city with the most extreme income inequality.

The growing wealth gap has given rise to the security-industrial complex, a burgeoning field aimed at assuaging the anxieties of the superwealthy. Multiple billionaire-security professionals I spoke with described an increased interest in security among their ultra-high-net-worth clients. Some are shelling out millions on highly trained bodyguards or deploying high-tech surveillance drones. Elon Musk travels with up to 20 bodyguards at a time. Others are building bunkers to wait out the apocalypse. In Indian Creek, if you somehow evaded the islandwide surveillance dragnet that Bezos and his neighbors have amassed through public funding, you’d still have to contend with the formidable private dragnets guarding their individual mansions.

Walled-off communities, by their very nature, lead to ever higher walls.

Security “has become a really big concern for billionaires now, because there’s never been more talk about the divide between the haves and the have-nots,” says Brian Daniel, who operates the Celebrity Personal Assistant Network, a company that connects billionaires to security staff. “It gets people worked up.” Never mind that poor people are statistically far more likely to be the victims of crime than those who can afford supermansions on private islands. Being rich means you can afford to be safe instead of sorry.

“Trapped,” a book coauthored by Low, the CUNY researcher, describes a growing movement to build communities that are “privatized, fortified, unequal.” By 2015, more than 11 million Americans had retreated to these “secured communities,” compared with 7 million a decade earlier. But rather than making residents feel safer, Low says, the intense focus on security and privacy only serves to cut them off from the public and stoke their anxieties about outsiders. Walled-off communities, by their very nature, lead to ever higher walls.

“Indian Creek is a great extreme example of trying to pull out completely from having anything to do with the rest of the world,” Low says. “The more you enclose yourself, the more you’re reminding yourself of a sense of risk.”

At a council meeting in 2022, not long after the installation of the perimeter-security system, Indian Creek residents were once again discussing the need to ramp up their security. This time, they worried the threat might be coming from inside the mansions. The police chief, John Bernardo, proposed a measure that would require any worker entering the island to submit to a criminal background check. Despite pushback from some residents who were concerned that the policy would make hiring more difficult, the council came down largely in support of the idea.

For Mayor Klepach, the background checks were just a starting point. More wealth leads to more workers — and every worker is a potential threat.”Especially when you have so many houses going up and a caravan of employees coming in and out of here,” the mayor said, “we could do so much more.”