Intel’s next CEO needs to decide the fate of its chip fabs

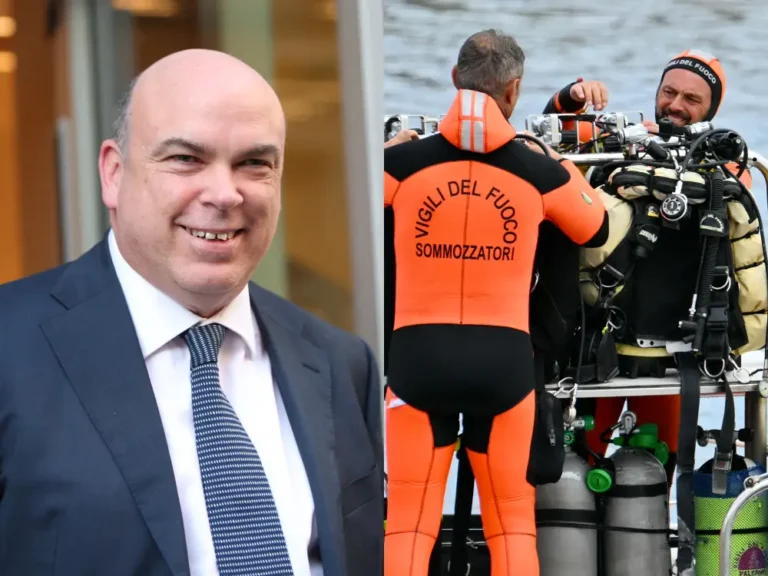

Former Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger holding up a chip at a US Senate hearing.

One central question has been hanging over Intel for months: Should the 56-year-old Silicon Valley legend separate its chip factories, or fabs, from the rest of the company?

Intel’s departing CEO, Pat Gelsinger, has opposed that strategy. As a longtime champion of the company’s chip manufacturing efforts, he was reluctant to split it.

The company has taken some steps to look into this strategy. Bloomberg reported in August that Intel had hired bankers to help consider several options, including splitting off the fabs from the rest of Intel. The company also announced in September that it would establish its Foundry business as a separate subsidiary within the company.

Gelsinger’s departure from the company, announced Monday, has reopened the question, although the calculus is more complicated than simple dollars and cents.

Splitting the fabs from the rest of its business could help Intel improve its balance sheet. It likely won’t be easy since Intel was awarded $7.9 billion in CHIPS and Science Act funding, and it’s required to maintain majority control of its foundries.

Intel declined to comment for this story.

A breakup could make Intel more competitive

Politically, fabs are important to Intel’s place in the American economy and allow the US to reduce dependence on foreign manufacturers. At the same time, they drag down the company’s balance sheet. Intel’s foundry, the line of business that manufactures chips, has posted losses for years.

Fabs are immensely hard work. They’re expensive to build and operate, and they require a level of precision beyond most other types of manufacturing.

Intel could benefit from a split, and the company maintains meaningful market share in its computing and traditional (not AI) data center businesses. Amid the broader CEO search, Intel also elevated executive Michelle Johnston Holthaus to CEO of Intel Products and the company’s co-CEO. Analysts said this could better set up a split.

Regardless, analysts said finding new leadership for the fabs will be challenging.

“The choice for any new CEO would seem to center on what to do with the fabs,” Bernstein analysts wrote in a note to investors after the announcement of Gelsinger’s departure.

On one hand, the fabs are “deadweight” for Intel, the Bernstein analysts wrote. On the other hand, “scrapping them would also be fraught with difficulties around the product road map, outsourcing strategy, CHIPS Act and political navigation, etc. There don’t seem to be any easy answers here, so whoever winds up filling the slot looks in for a tough ride,” the analysts continued.

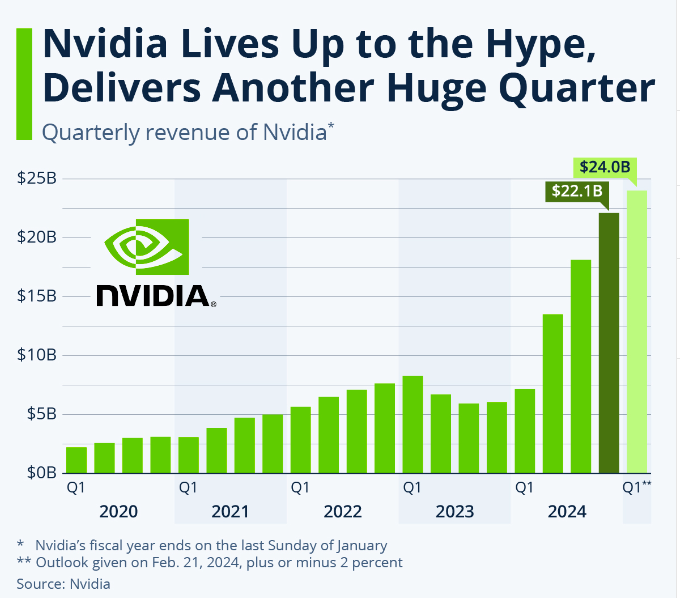

Intel’s competitors and contemporaries are avoiding the hassle of owning and operating a fab. The world’s leading chip design firm, Nvidia, outsources all its manufacturing. Its runner-up, AMD, experienced similar woes when it owned fabs, eventually spinning them out in 2009.

Intel has also outsourced some chip manufacturing to rival TSMC in recent years — which sends a negative signal to the market about its own fabs.

Intel is getting CHIPS Act funding

Ownership of the fabs and CHIPS Act funding are highly intertwined. Intel must retain majority control of the foundry to continue receiving CHIPS Act funding and benefits, a November regulatory filing said.

Intel could separate its foundry business while maintaining majority control, said Dan Newman, CEO of The Futurum Group. Still, the CHIPS Act remains key to Intel’s future.

“If you add it all up, it equates to roughly $40 billion in loans, tax exemptions, and grants — so quite significant,” said Logan Purk, a senior research analyst at Edward Jones.

“Only a small slice of the commitment has come, though,” he continued.

Intel’s fabs need more customers

Intel is attempting to move beyond manufacturing its own chips to becoming a contract manufacturer. Amazon has already signed on as a customer. Though bringing in more manufacturing customers could mean more revenue, it first requires more investment.

There’s a more ephemeral reason Intel might want separation between its Foundry and its chip design businesses, too. Foundries regularly deal with many competing clients.

“One of the big concerns for the fabless designers is any sort of information leakage,” Newman said.

“The products department competes with many potential clients of the foundry. You want separation,” he added.

It was once rumored that a third party might buy Intel. Analysts have balked at the prospect for political and financial reasons, particularly since running the fabs is a major challenge.