JPMorgan’s junior bankers just gained an ally in their fight against overwork. Here’s what we know about the longtime exec tapped to advocate for them.

Ryland McClendon

Last week, JPMorgan Chase announced that it would be seeking to limit junior bankers’ work hours to 80 per week to tackle concerns over unhealthy working conditions. Now, the bank seems to be showing it means business by tapping an investment banker turned HR executive to enforce its new rules.

In a memo obtained by CNBC, JPMorgan said it named managing director Ryland McClendon to be the investment bank’s “associate and analyst leader,” a role it created to oversee the “well being and success” of its junior investment bankers.

The appointment comes amid growing concerns about the work life of junior investment bankers following the death of Leo Lukenas, a 35-year-old Bank of America associate who died of acute coronary artery thrombus, which is a type of blood clot. Lukenas reportedly complained leading up to his death about an exhausting work schedule, including 100-hour work weeks.

Little is known so far about McClendon, an HR exec who has been at JPMorgan for about 14 years, or how she plans to tackle her new role. JPMorgan declined to make her available for an interview.

In an effort to understand McClendon’s potential approach to the position, B-17 put together everything we could find publicly about her background and JPM’s plans for the job. Here’s what we know.

Inside McClendon’s new role

Efforts to protect junior bankers have failed in the past, and skepticism continues to be raised over the latest guardrails introduced by JPMorgan and Bank of America.

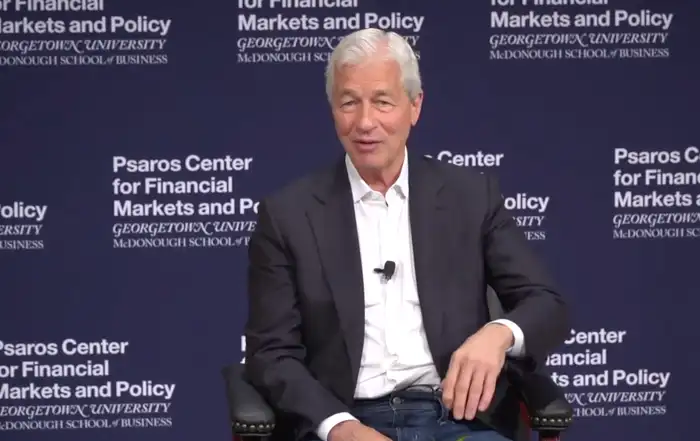

Earlier this week, however, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon offered the first concrete hints about how his bank’s program might work.

“We actually hired someone who is going to do nothing but manage the analyst and stuff so they can actually track it,” Dimon revealed at a Georgetown University financial conference, presumably referring to McClendon.

He suggested that the first priority will be tracking hours and ensuring they are accurately reported.

“First of all, we want kids to tell the truth,” he said. “Some kids are saying they work more hours than they do. Some kids are saying they work less hours than they do so they get more work.”

Another priority, he said, will be to “teach” senior bankers — who manage the analysts and associates — how to dole out assignments so junior bankers aren’t left scrambling to get things done at the last minute, especially on weekends.

“So a lot of investment bankers — they’ve been traveling all week. They come home, they give you four assignments, and you gotta work all weekend. It’s just not right,” he said, adding, “Assignments should be given out by Wednesday, not on Friday night.”

Lastly, Dimon called for consequences for senior bankers who don’t take the new policies seriously. That means standing up to them with the message that “You’re violating, you gotta stop,” he said, adding, “And it will be in your bonus – so people know we actually really mean it.”

Jamie Dimon on Tuesday addressed Ryland McClendon’s new job

The investment banker’s daughter

McClendon grew up near Atlanta, Georgia with her parents and three siblings. Her father was an investment banker, and her mother was a longtime public administrator.

Her dad, Raymond J. McClendon, ran the Atlanta investment firm Pryor, McClendon, Counts and Co., which helped the city of Atlanta raise money through the sale of bonds for what is now the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, according to news reports from the early 1990s. The firm also helped finance the city’s MARTA public metro system, which McClendon’s mother later helped lead.

McClendon’s mother, also named Ryland, was named the first Black person and the first woman to chair Atlanta’s public transit system board of directors in the early 1990s. Before that, she was a transit aide to Washington D.C. mayor Marion Barry.

In a 2023 episode of JPMorgan’s “Women on the Move” podcast, McClendon said her career path has been heavily influenced by her parents.

“I went to Duke. I majored in econ and public policy. And where did that come from? The strong influence of my parents.”

McClendon also said on the podcast that she enjoys solving particularly tricky problems.

“I’m the person that loves logic puzzles and Sudoku and all those things. So like, the hairier the problem, the more excited I get,” she said on the podcast.

Her time as a junior banker

After graduating from Duke in 2007, McClendon started working at SunTrust’s investment banking arm: SunTrust Robinson Humphrey, according to her LinkedIn. There, she said on the JPM podcast, she had her own experiences feeling frustrated as a junior banker.

“When I started, the market was like this, it was 2007. Then it crashed, so we were all just happy to have jobs,” she said. But after the labor market had started to thaw, “nobody was talking to us about getting promoted. It got to a point where it’s really frustrating and everybody just said, ‘Oh, keep doing what you’re doing and it’ll come.’ And that just didn’t sit well with me.”

About three and a half years into that job, McClendon explained, she met a JPMorgan banker at a client meeting in Florida.

“About a month later, she called me up and said, “Hey, we’ve got an associate role in our Atlanta office. Are you interested?” And I said, sure. And so I interviewed and got the role.”

That role was in JPM’s corporate banking & specialized industries team, where she began as an associate in 2010 and stayed for nearly seven years.

The switch to HR

In 2017, she moved to the firm’s talent team and headed campus recruiting for the commercial bank, citing “organizational changes” and learning that a promotion in banking might be further off than she had hoped.

“There were some organizational changes happening, and I said, okay, this feels like a good time to kind of put some feelers out there, look at some other things, which I did,” she said on the JPM podcast.

“I had to silence my ego a little bit. I was on this path … a third-year VP in corporate banking. I was this close, I felt like, to getting my own clients,” she said. “It wasn’t easy, and it did hurt.”

She recalled calling up her mentor at the time, who she described as the “head of the business.”

“He said, you know, this is a long haul and there’s some skills that kind of put you in the middle of the pack that you may not get there in the timeframe you want to get there in. And he said, I’m saying this to you not to make you feel bad. I’m saying this to you because I love you and I care about you. I really had to listen. As much as it hurt, I kind of just had to let go,” she said, adding, “And I’m so glad that I did because it put me on a path to doing work that was more fulfilling for me personally and professionally and stretched me in different ways.”

In 2019 McClendon became head of career development programs. About two years later, she got a big call from the then-head of diversity and inclusion for the investment bank, who told her she had already recommended McClendon to replace her. She was indeed chosen for the role in 2021.

Heading DEI on Wall Street

Past reports describe McClendon’s mom as someone skilled in “forming coalitions” and getting other people to her side — skills the junior McClendon appears to also have practiced in her role as the head of diversity, equity, and inclusion for corporate and investment banking at JPMorgan.

In the 2023 podcast, McClendon said she likes to use storytelling as a tool to educate because it can be more effective than numbers alone. She explained that when presenting to a group, for example, she likes to “strategically” insert stories in with raw data to make an impression.

“They can remember maybe one or two facts and figures, but what’s really going to move them, what they’re going to be talking about months and even years from now is the stories that they hear,” she said.

During the podcast, she went on to share a particularly defining experience she witnessed as a young child in her “predominantly white” neighborhood — a neighbor approached her then-teenaged older brother with a gun in front of their home after jumping to the conclusion that the teen was trying to steal her father’s car.

“My mom, fortunately, was upstairs and looked out the window and saw it. And so she raced downstairs, ran out the front door screaming my brother’s name so that the guy would know, he lives here, we know him, this is not what you think it is. I was a young child at the time, but it was really eye-opening for me,” she said.

The point, she said, is to use stories to bring people into each others’ worlds and experiences — a tool she could use in her role as junior banker protector.

“Storytelling is the most powerful tool we can use,” she said.