Meet the generation that may never retire: Why some millennials are behind on savings — and how they can catch up

A few years ago, Nathaniel Hudson-Hartman, 38, calculated that he’d need about $1.5 million in savings to retire comfortably in his sixties.

“I was making roughly $50,000 a year between my W-2 job and gig work, and I hope to enjoy retirement for about 30 years,” he said.

As of March, the Portland-based gig driver had roughly $100,000 in his 401(k) from a previous job and about $12,000 across other savings and investment accounts.

In other words, he still has a ways to go.

The average millennial said they expected to need about $1.7 million in savings to retire comfortably, according to a Northwestern Mutual survey of 4,588 US adults conducted by the Harris Poll between January 3 and January 17. However, the average millennial reported roughly $63,000 in retirement savings so far.

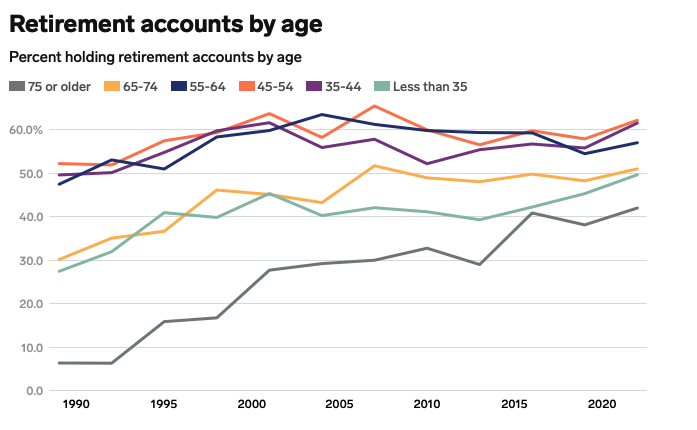

Meanwhile, the Census Bureau’s 2022 survey of consumer finances found that only about 62% of Americans between the ages of 35 and 44 had a retirement account like a 401(k), and among those who did, the median balance was $45,000.

A common rule of thumb when it comes to retirement savings is that by age 30, one should have saved up 100% of what they make in a year. So if one earns a $75,000 salary at 30, they should have $75,000 in total across their savings, retirement accounts, and other assets. While millennials will need more money to retire comfortably, many are far away from the savings milestone experts suggest.

Millennials are at risk of not having enough money to retire, a reality many in the boomer generation are currently experiencing. As a result, some boomers have postponed their retirements or returned to the workforce. According to 2023 Pew Research data, nearly 20% of Americans aged 65 and older are working. That number was 11% in 1987.

However, millennials have their own unique set of obstacles compared to boomers. Millennials are more saddled with student debt than prior generations and face some of the worst housing affordability levels relative to income ever seen. What’s more, the future of the US Social Security system is uncertain, and longer expected lifespans — while a positive development — will require more retirement savings.

How to figure out how much retirement savings you need

Tiffany Bell, a 36-year-old business management professional based in Houston, didn’t always take retirement savings seriously.

When she was 23, she said she didn’t participate in her company’s 401(k) plan. But after about a year of “chastising” from one of her supervisors, she said she finally gave in.

“Their harping significantly changed the course of my life over the next decade.

Over the past 10 years, Bell said she’s meticulously tracked her budget and focused on saving. She now has roughly $280,000 in savings and retirement accounts.

That’s way ahead of many of her peers, but it might not be enough.

Bell would like to retire around age 65 but isn’t sure this will be possible. Using the NerdWallet retirement calculator, she estimated she’d need several million dollars in savings to retire comfortably. Assuming a 4% annual investment return on her $280,000 savings, she’d have about $900,000 in 30 years, her target retirement date. She’d have to invest an additional $40,000 each year to get to $3 million in savings by age 65.

Initially, she put into the calculator that she’d need 80% of her annual pre-retirement income — which is currently in the six figures — to maintain her lifestyle in retirement. But when the calculator spit out a savings goal of over $6 million — which felt impossible — she tried 40% instead. This provided a $3 million savings goal, which she said still felt out of reach, but is a more realistic goal for now.

“Ideally, I’d like to overshoot the target and actually have something to pass down to family,” she said. “But it is depressing to think I might not even be able to save enough for myself.”

Fidelity recommends that people plan to need between 55% and 80% of their annual pre-retirement income to fund a retirement lifestyle they’re satisfied with, though it depends on one’s personal circumstances.

While saving for retirement can be a challenge, developing retirement savings goals — and figuring out if they’re realistic — is a crucial yet complicated part of the process.

For example, the suggestion that people should have saved 100% of their salary by age 30, has many issues, experts say. One of them is that people don’t always start working at the same point in their 20s, said Chris Chen, a certified financial planner and cofounder of financial advisory firm Insight Financial Strategists.

“A lot of the time, when kids graduate from college, not very long thereafter, there might be graduate school, and that’s going to put a dent in their style,” Chen said. “And for these people, getting to the level of one-times earnings can be very difficult.”

Meanwhile, he said, salaries for those who don’t go to graduate school often won’t be as high as those who do.

Another problem with the rule is that the cost of living varies greatly depending on where one lives, says Judi Leahy, senior wealth advisor for Citi Personal Wealth Management. In big cities, costs are going to be much higher, but this is where job opportunities for some industries are concentrated.

Initially, she put into the calculator that she’d need 80% of her annual pre-retirement income — which is currently in the six figures — to maintain her lifestyle in retirement. But when the calculator spit out a savings goal of over $6 million — which felt impossible — she tried 40% instead. This provided a $3 million savings goal, which she said still felt out of reach, but is a more realistic goal for now.

“Ideally, I’d like to overshoot the target and actually have something to pass down to family,” she said. “But it is depressing to think I might not even be able to save enough for myself.”

Fidelity recommends that people plan to need between 55% and 80% of their annual pre-retirement income to fund a retirement lifestyle they’re satisfied with, though it depends on one’s personal circumstances.

While saving for retirement can be a challenge, developing retirement savings goals — and figuring out if they’re realistic — is a crucial yet complicated part of the process.

For example, the suggestion that people should have saved 100% of their salary by age 30, has many issues, experts say. One of them is that people don’t always start working at the same point in their 20s, said Chris Chen, a certified financial planner and cofounder of financial advisory firm Insight Financial Strategists.

“A lot of the time, when kids graduate from college, not very long thereafter, there might be graduate school, and that’s going to put a dent in their style,” Chen said. “And for these people, getting to the level of one-times earnings can be very difficult.”

Meanwhile, he said, salaries for those who don’t go to graduate school often won’t be as high as those who do.

Another problem with the rule is that the cost of living varies greatly depending on where one lives, says Judi Leahy, senior wealth advisor for Citi Personal Wealth Management. In big cities, costs are going to be much higher, but this is where job opportunities for some industries are concentrated.

“If you’re living in New York, it’s going to be harder to save money than if you’re in Montana,” Leahy said.

While financial advisors say you should have savings that equal your salary at 30, they recommend that people have three times their annual salary saved by 40.

While still difficult, this one should be easier to achieve, in part because of the law of compound interest on previous savings, Chen said. When one is invested in securities like a bond or dividend-paying stock, they can choose to reinvest the yields they earn. Doing this repeatedly then snowballs the total return for the investor.

In addition to speaking with a financial advisor, some free online retirement tools — like those from Vanguard, Bankrate, and NerdWallet — may be able to help people develop more personalized retirement goals.

But these tools aren’t without their limitations. Bell — who used one of those calculators — said her future is too uncertain to accurately assess her retirement needs. For instance, Bell doesn’t know where she’ll be living when she retires and if that home will be paid off. What’s more, she can’t anticipate what health needs she’ll have when she stops working.

“I have no idea where I’ll be at that point in my life,” she said. “To me, it seems almost impossible to guess what is really needed.”

To be sure, many millennials may feel similar to Bell: It can seem impossible to predict how much you’ll need for possibly 20 or 30 years of your life without an annual salary. Even if someone saves what they think is enough, there’s no telling exactly how much they’ll need for any family emergencies or health crises that arise. If it turns out they haven’t saved enough, the lack of a social safety net in the US means they may be forced to work well past their desired retirement age.

How millennials can get their retirement savings back on track

While some millennials are struggling financially, it’s not all doom and gloom when it comes to their retirement prospects.

A Vanguard report released in October found that early millennials — people between the ages of 37 and 41 — were better positioned for retirement than older generations. Vanguard attributed this in part to the passage of the Pension Protection Act in 2006, which it found made it easier for Americans to join their workplace retirement plans and increase their savings rates over time.

In a Fidelity survey conducted last December — in partnership with consumer research firm Big Village — of more than 2,000 US adults with an investment account, 75% of millennials surveyed said they were confident they’d be able to retire when and how they want. The survey found that millennials started saving for retirement earlier than both Gen X and boomers. What’s more, Fidelity research published last year found that, since 2020, millennials have seen a larger increase in median income than any other generation.

But experts say that for the other millennials who are behind on their retirement savings, there are a few tricks that can make up for lost time.

First, start saving whatever you can, when you can. Nilay Gandhi, CFP senior wealth advisor at Vanguard, told Business Insider that he recommends people put between 10% and 15% of their annual pre-tax income toward retirement savings.

Second, make sure you are putting money into a retirement account like a 401(k) or a Roth IRA — which offers diversified investments and tax advantages — and getting any deposit matches that your company might offer. Many firms match deposits up to a certain percentage of an employee’s salary. The maximum one can contribute to a Roth IRA, which is funded by post-tax deposits, is $7,000 in 2024. For a 401(k), which is for pre-tax deposits, the maximum this year is $23,000.

“They should religiously put their money in there, whether it is the Roth version or the traditional version, and at the very least pick up the match,” Chen said.

Third, if you have an investment portfolio, make sure it has the right mix of stocks, bonds, and cash.

Leahy said that those in their 30s may want to think about leaning more heavily into stocks given their longer investing timeline and higher risk tolerance. Older investors may want to consider higher allocations to safer options like fixed-income assets, she said.

“If you’re trying to play catch up at 45 or 55 and you think you want to go all in on equities, it might not be your best bet,” she said.

The concern for some millennials isn’t that they don’t have the money to put toward retirement savings, it’s that they’re investing it too conservatively, Rita Assaf, vice president, retirement savings at Fidelity Investments.

Assaf said Fidelity’s research found that millennials have seen the largest drop in “age-appropriate asset allocation,” meaning they’re holding too much of their savings in cash and bonds than she would typically recommend.

“These indicators point toward a trend of millennials taking a more conservative approach to investing, which likely stems from the fact they have multiple other savings priorities of their own,” she said. “The concern is that millennials may not end up with the appropriate mix of assets to help them adequately achieve their retirement goals.”

While a solid investment strategy is important, allocating more money toward saving is the most important step.

“If an individual is not saving enough, even the best investment strategy is unlikely to help them reach their goal,” Gandhi said.

Savings outside a retirement account are also important, Chen said, and one should start by building up at least six months of expenses for an emergency fund. One way to do this is to have money deposited directly from their paycheck into a separate account. And with certificates of deposit paying annualized rates around 5% at the moment, Leahy said savers are even more incentivized to hold onto their money.

Both Leahy and Chen also agreed that credit card use should be avoided for those who are not highly confident that they can pay off their balance every month.

“Do not maintain a credit card balance. That’s a great way to erode capital because the card is charging you anywhere from 12% to 22%,” Leahy said. “So that item that you bought that was on sale that you really didn’t need wasn’t worth it.”

But for some millennials, following most of this advice might not be enough for them to reach their retirement goals. It could force them to join the millions of Americans working well into their sixties and later.

Bell, for example, has started coming to terms with the possibility that she might have to work later in life than she initially hoped.

“I’m fortunate to be in an industry that allows you to work well past retirement age because it’s not very physically intensive,” she said.

Similarly, Hudson-Hartman said he takes comfort from the fact he enjoys working — and has an income stream he can count on well past age 70 if necessary.

“I always planned to do gig work part-time in my later years,” he said. “I plan to just dial it back and work during busy times and keep my mornings and afternoons free.”