Meet the professor who just won the Millennium Technology Prize — and $1.1 million

Professor Bantval Jayant Baliga previously worked at General Electric.

Just a few years after Bantval Jayant Baliga started working at General Electric in the 1970s, word of a discovery he made went all the way to CEO Jack Welch.

As an electrical engineer at the time, the now 76-year-old Baliga had developed the beginnings of what’s known as an insulated-gate bipolar transistor, or IGBT. It promised to make electrical devices a whole lot more efficient. Greater efficiency would mean bigger cost savings.

So once Welch, the towering leader of the American conglomerate, caught wind of an idea with the potential to reduce his costs, he was ready to be pitched. “In half an hour, I convinced him this is a great idea,” Baliga tells B-17.

Since then, his invention of the IGBT semiconductor device has made its way into the wider world of electronics, delivering electrical efficiency and helping reduce carbon emissions in everything from medical devices and consumer appliances to hybrid electric vehicles.

In 2016, it helped earn him a place in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Now he’s become the latest recipient of the Millennium Technology Prize — a 1 million euro ($1.1 million) award presided over by the president of Finland that spotlights innovations beneficial to society.

“It’s like a capstone for my career,” he says.

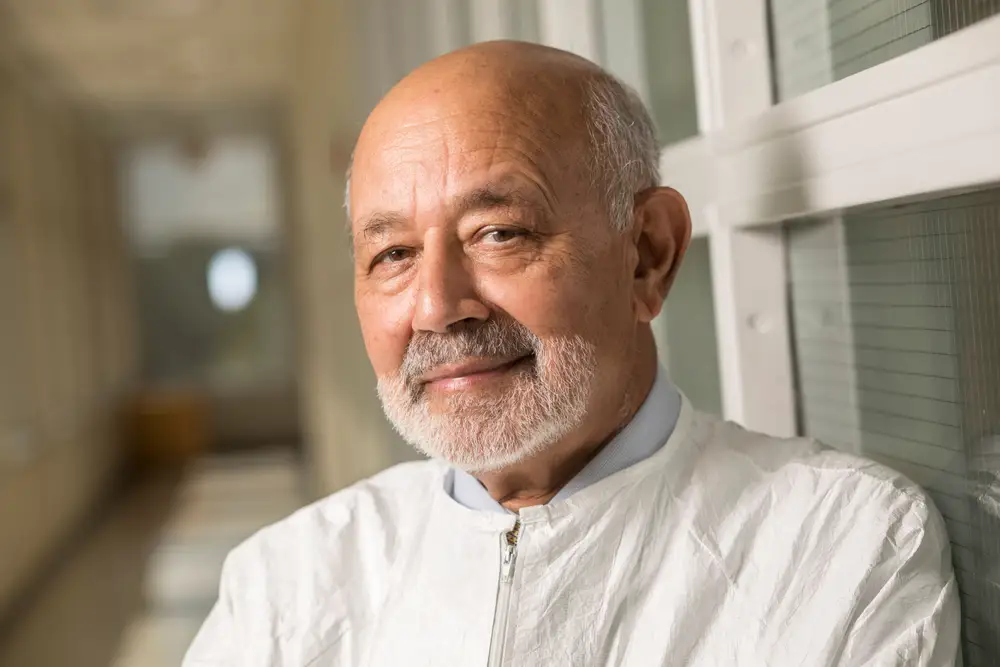

Professor Baliga has won several prizes following his invention of the IGBT.

Baliga’s career started as an undergraduate student at the Indian Institute of Technology in Madras, where — like so many others of his time — he became enthralled with the legendary lectures delivered by physicist Richard Feynman in California in the 1960s.

“It was not in my curriculum, but in our bookstore,” he said. “I used to read when other students were going to the movies. It just inspired me.”

From there, a doctorate in electrical engineering in the US led to an initial role at General Electric, where he spent his time working in the world of transistors and thyristors at a time when the semiconductor industry was “already considered very mature,” Baliga recalls.

Fast track

Though that meant a big breakthrough would be tough to come by, he was full of ideas that could have a huge impact, particularly on how electrical efficiency could be improved in the full roster of products his employer was working on.

After his pitch to Welch, Baliga was given the rare opportunity to fast-track a nascent idea from a research phase straight into manufacturing on a production line in California.

Concern about global warming then was far less acute. However, it later became clear that reducing the electrical consumption of devices with IGBTs — found in everything from CAT scanners and microwaves to refrigeration and Japan’s bullet trains — would have a huge positive downstream impact on carbon emissions.

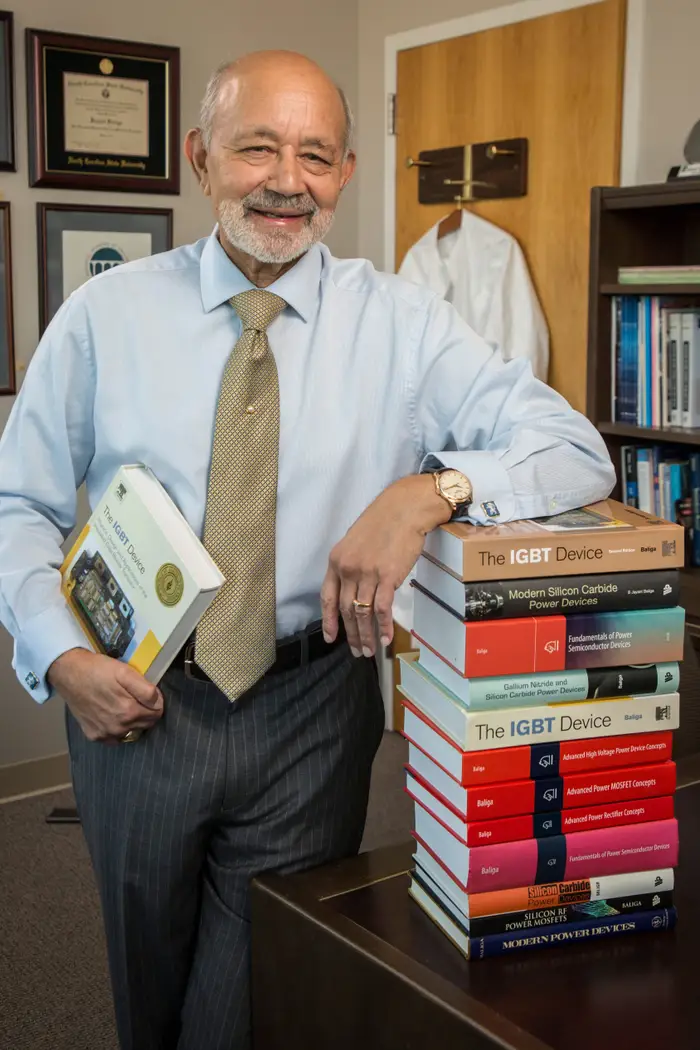

IGBTs can be found in everything from domestic appliances to bullet trains.

By Baliga’s own calculations, IGBTs have helped reduce global carbon emissions by more than 82 gigatons, or 180 trillion points, between 1990 and 2020 through reduced electrical energy and fuel consumption.

“Two-thirds of the electricity in the world is used to run motors in consumer and industrial applications,” says Professor Päivi Törmä, chair of the International Selection Committee of the Millennium Technology Prize. “Professor Baliga’s innovation has allowed us to develop societies with electricity efficiently, while dramatically reducing energy consumption.”

Baliga, who has worked as a professor at North Carolina State University since his time at General Electric, knows there’s more work to be done to ensure the world of electronics and semiconductors reduces electricity consumption.

In particular, Baliga sees the world of artificial intelligence, which has seen a huge burst of growth in recent years, consuming a lot of power.

Staying true

In July, for instance, Google revealed that its total greenhouse gas emissions had increased 48% since 2019, something it put down to “increased data center energy consumption and supply chain emissions.” Baliga and his team, then, are working on new inventions to improve “power delivery for AI servers.”

As he looks back on half a century of work, he recalls that his award-winning invention would not have come to be had he not stayed true to a note he made in his application to attend university in the US: “Develop a technology that would benefit mankind.”

“That’s a naive idea for a young 21-year-old, but it actually came true so how about that,” Baliga says. “So my encouragement for young people: be ambitious but do something that is socially beneficial as well.”