Miami’s beachfront high-rises are sinking fast. It’s a warning for coastal properties worldwide.

High-rises on barrier islands near Miami are sinking, a new study found.

Coastal properties worldwide are sinking, including some of Miami’s pricey waterfront high-rises.

In a study published in the journal Earth and Space Science in December, researchers found that 35 buildings along the coasts of Miami’s barrier islands have sunk into the ground by 2 to 8 centimeters between 2016 and 2023.

This sinking phenomenon, called subsidence, is happening “almost everywhere that we look,” said Manoochehr Shirzaei, a geophysicist at Virginia Tech who was not involved in the Miami-area study.

That sinking can lead to expensive — and sometimes deadly — damage and flooding in some of the most populated places on Earth. It doesn’t have to, though.

The new Miami study shows how satellites can help save buildings and infrastructure before the sinking contributes to catastrophic failure.

Coastal cities’ sinking problem

Cities all over the world weigh so much and draw so much groundwater from beneath them that they’re sinking into the ground. It’s been documented on every continent.

Sinking coastal cities are extra vulnerable because the seas are rising to meet them, doubling the flood risk.

“One centimeter of sea level rise and one centimeter of subsidence each have the same effects” on flooding hazards, the lead authors of the new Miami study, Farzaneh Aziz Zanjani and Falk Amelung, told B-17 in an email.

Many of the most afflicted coastal cities are in eastern and southern Asia, but major hubs in Europe, Africa, and Australia are also sinking rapidly.

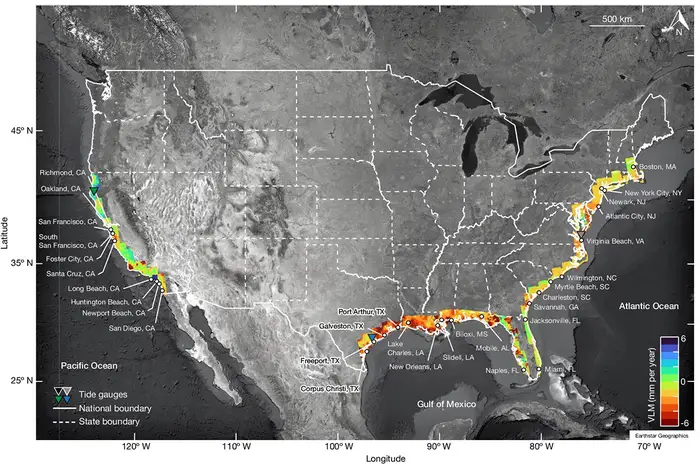

In the US, Shirzaei’s research group found that huge swaths of the East Coast — including New York and Baltimore — are sinking by at least 2 millimeters each year.

In a follow-up study, Shirzaei’s research group found Gulf Coast cities sinking even more.

Mapping from Shirzaei’s research shows vertical land motion (VLM) along the US coasts. Red and orange indicates sinking. Green and blue indicate land rising.

Expensive flood risks and structural damage

Despite its prevalence, subsidence isn’t usually factored into future flooding estimates.

By combining it with sea-level rise projections, Shirzaei’s group estimated that up to 518,000 more Americans will be exposed to high tide flooding by 2050 in up to 288,000 more properties, amounting to $109 billion in property value.

It’s not just flooding, though. Subsidence can also compromise a building’s structural integrity.

Flood waters inundate a neighborhood in Hallandale Beach, Florida.

“The situation becomes concerning when different parts of the building move at varying rates,” Aziz Zanjani and Amelung said.

“This can cause structural damage, such as cracks or distortions, which could compromise the building’s safety over time,” they added.

Knowing if and how buildings are sinking could help prevent future damage. That’s where the Miami researchers’ study comes in.

Satellites can spy hot spots before they sink too far

After the 2021 collapse of the Champlain South Condominium Tower in Surfside, Florida, which killed 98 people, Miami researchers began to wonder if the ground beneath that building was part of the problem.

When they assessed satellite data, they didn’t find any indication of subsidence before the incident, which surprised them because so much construction was happening in the area.

They’d found that the subsidence of other buildings was associated with nearby construction. The researchers think the difference is sand.

The limestone underground might be interspersed with sandy layers in the barrier islands. Vibrations from construction could cause the sand grains to shift and give way under the buildings’ weight.

Though there are likely other factors at play, having such a specific link to the subsidence of specific structures can be helpful. That’s the first step in solving a building’s sinking problem.

“It would be incredibly helpful if this type of information were more readily available to researchers,” Aziz Zanjani and Amelung said.

The Miami researchers are seeking more funding to study Miami’s sediments and investigate uneven subsidence, where different parts of a building sink at different rates.

Shirzaei said satellite remote-sensing could be a diagnostic tool to scan specific regions — such as Miami’s barrier islands — for buildings tilting on uneven land subsidence. Then, investigators can target at-risk spots and, if necessary, suggest structural reinforcements.

After all, the Miami scientists wrote in their paper, “There are no indications that subsidence will come to a stop.”