My partner and I were together for 13 years but our marriage lasted only a year. Our divorce was no one’s fault.

I was married on a cold day in December. Thirteen months later, my husband moved out. We decided to separate in November after agreeing to spend the holidays with our families. We told just a few friends, thinking maybe this was temporary. But the weeks between were a problem. After over a decade celebrating the anniversary of the spring night he kissed me — a hotel elevator, a high school trip — now there was the date that marked the night he kissed me in his mother’s living room, where we exchanged rings and signed papers.

We had been together for 13 years, lived together for 5, and now, were we supposed to celebrate the one year we barely managed to stay married? Well — we made dinner reservations. Not knowing what to do or where to look, we talked about what we had done that day, our jobs. I tried to be careful but couldn’t help making some reference to our situation, so he would know the strangeness was not lost on me.

“What was your favorite part of being married?” I asked, smiling to shield the was. He talked about our wedding, our move to a new city, and then he asked me the same question. “Being a family,” I said, and cried, but only a little.

We flew home. We saw our families, and we fought. We were cat-sitting for a friend and my husband spent his nights elsewhere. The cats had recently been kittens and were not yet adjusted to their adult sizes. They ran and played as though they might not knock over water glasses or pull out electrical cords. They were cute and they kept me awake all night. In the mornings, my husband — my handsome husband, I sometimes thought when I saw him, even after we decided to separate, because he was, still, both — would come home and feed them, and they would immediately fall asleep. God, I hated those cats.

On the first day of the New Year, we flew back to our apartment.

By the third day I was living there alone.

No-fault divorce has changed the way people separate

Every generation of North American is now alive at a moment when they have access to what is usually called “no‑fault” divorce, the legal dissolution of marriage that does not require a reason beyond choice. Those who have lived long enough to know the difference understand the significance of this freedom; those who will never know the difference have inherited a profound question of what divorce should be, who it is for, and why the institution of marriage maintains its power.

I have looked for guidance everywhere but real life. Through fiction and film, through gossip and conversation, through research about the past and speculation about the future, and most of all through work — always working, always writing. I have always preferred reading to reality. In reading, there’s the possibility for more than just what’s on the page, or the screen, or coming through the other end of the phone. In turning over what happened, the facts are just details, significance, just interpretation. This is evasive, and better still, very effective. I want you to ask if I’ve read Anna Karenina. I do not want you to ask what I would do for love.

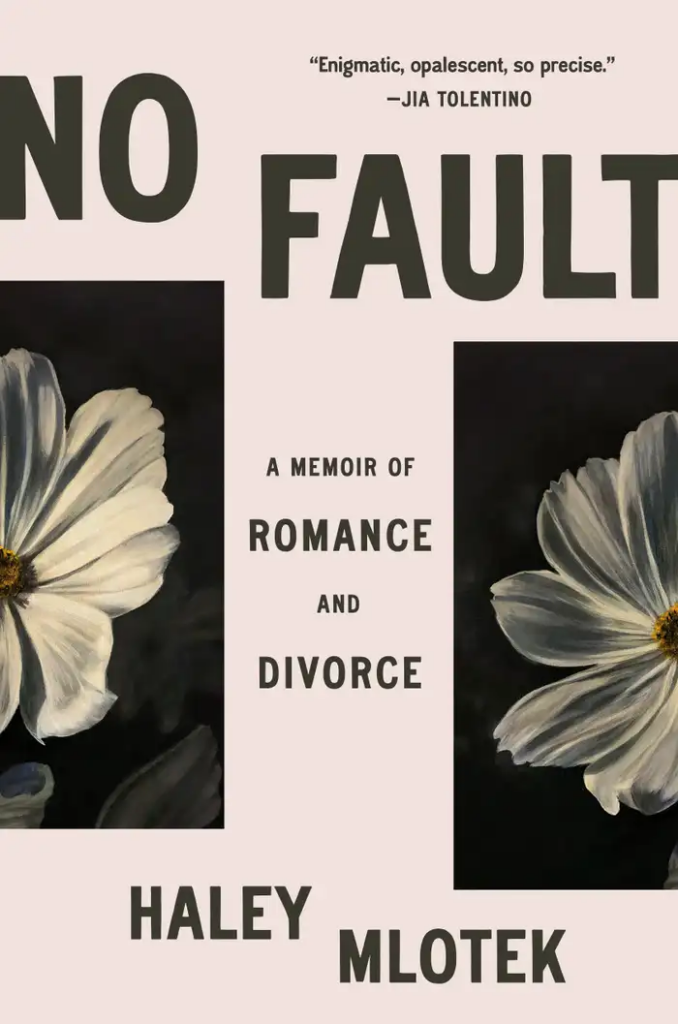

Haley Mlotek is the author of “No Fault: A Memoir of Romance and Divorce”

I have always been curious about the way people tell their stories

There are some incidents that seem to matter most and that becomes the story. Sometimes there’s risk or danger, tears or blood. A story about broken plates, the screen in the window, the sound of his voice. But what happened after? That is what I want to know.

When they both decided they had had enough, I want to ask: And then what? Did they go to bed, and if so, did they sleep in the same bed? What was it like the next morning — did they make coffee, or say goodbye before leaving for work? I prefer to see myself as audience, watching as though it didn’t happen to me. When remembering, I can see that in my story the worst happened twice, maybe three times. Then it was over.

I would like to observe my feelings more than feel them. This is, I know, the bad kind of romance: believing there’s meaning to be found if you could get the details right. Only some details matter, but I hold them all with the same weight. Every marriage requires that a couple agree on at least one part of the story: the ending.

I once watched as a person trying to explain something took her pen to paper. Here was a circle, she said, and this was the way most people experienced their memories: as events linked in one round dance with each other, the lines between the beginning of their consciousness and a space stretching out in front yet to be lived.

But then there was the way it happened, and the way it was remembered: as a spiral that started low, grew wide, and lapped around and around, touching occasionally, as we perhaps regressed or lagged or repeated a bad habit or spent time in a stage we thought was over. That’s the way I find myself trying to describe these years. Not backward and forward, or up and down, but around and around and around and around.

I, like so many, first inherited my knowledge of divorce from my family. Then came my own divorce. On the last day my husband and I lived together, I gave him my largest suitcase — the one I had used often during the one year we were married, traveling for work away from our home, and almost never in the 12 years of our relationship that preceded it — and watched the beginning of him packing.

I left before he finished. It took one more year after that day before I told most of my friends and family and loved ones. In that year my life changed so much I couldn’t recognize it as my own, while many more days revealed only what I should have already known. Maybe I was waiting until I could tell the difference. Maybe I was waiting until I felt ready. Mostly I was just waiting.