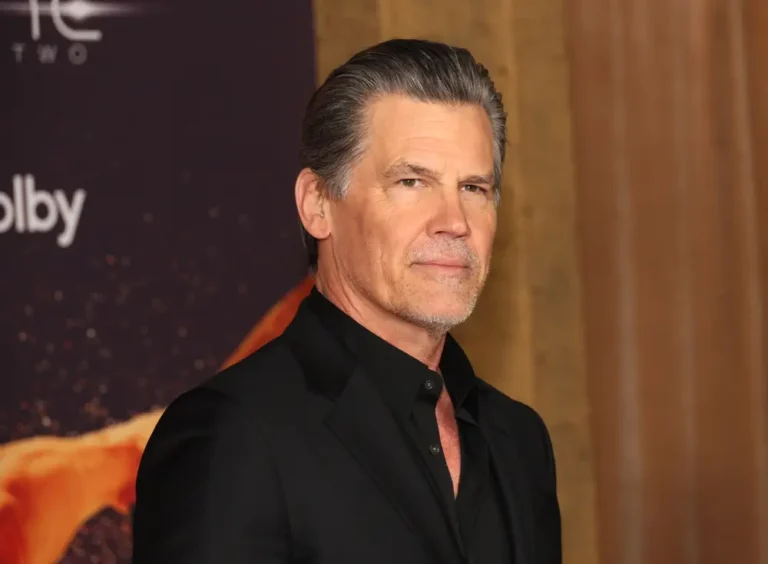

My son’s ADHD and autism diagnosis led to mine. At 37, I struggled to accept it at first.

The author was diagnosed with ADHD and autism at age 37.

As a special educator working with neurodiverse students for a decade, I didn’t realize I was neurodivergent myself until I was 37.

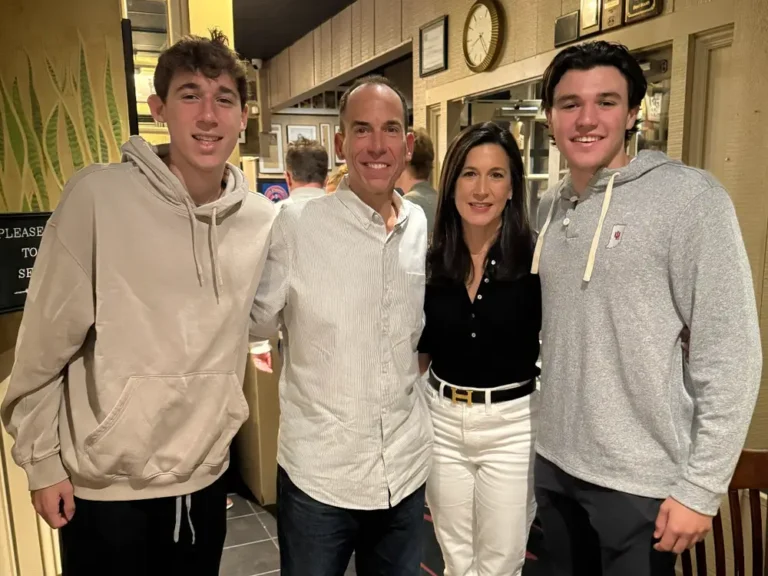

My son always had high energy compared to his siblings, but he didn’t have typical signs of ADHD or autism. He walked, talked, and had impressive social skills early. His challenges weren’t clear to me until he started school in person.

When his teacher asked him to show math solutions “three ways,” he argued and then ran from the classroom. When his principal told him he couldn’t spend the day wandering around the hallways, he said, “Why? I’m being safe.”

I saw myself in him

Confronted with his escalating behaviors, I recognized the same issues from my childhood, though I never acted on the impulse to leave the classroom when I was overwhelmed.

I worked closely with his psychiatrist. We needed to help my son find stability and support his brain chemistry so he could regulate his emotions, make friends, and stay in class. He was officially diagnosed with autism and ADHD at age 6.

Then the doctor offered to evaluate me. At first, I said no. As a single working mother of three, holding a successful long-term job in education and the arts, I saw myself as calm and fairly relaxed. But then figured, why not?

My perspective shifted after the psychiatrist completed the evaluation and informed me that I have both ADHD and autism. A study from 2022 shows that ADHD can cooccur in approximately 40% to 70% of people with a diagnosis of autism, and both run in families.

She explained that hyperactivity — especially in late-diagnosed women like me — can happen internally. It manifested in my propensity to overcommit, to make quick sometimes impulsive decisions, and to frequently annoy my friends and romantic partners by interrupting when I was excited about their ideas. The most illuminating part of my diagnosis had to do with routines, sensory issues, and masking.

I struggled to accept the diagnosis at first

While I appeared to be an organized, thorough person, I spent a lot of energy mapping out my day, repeatedly running through to-do lists in my head. I managed anxiety with sensory seeking behaviors like extreme workouts and hot yoga. My doctor emphasized the ritualistic way I cleaned my home and finished work tasks.

I struggled to accept the diagnosis. Unlike most of my clients who’d been diagnosed with autism, I was pretty good with language: a professional scribe, speech-language pathologist, and college writing teacher. My doctor was unfazed. She said she diagnosed women like me all the time, that it was a myth that neurodivergent people struggled with linguistic and communication skills.

My doctor asked me questions about how I learned to connect with others. As I answered, it became apparent that I spent a great deal of time watching people, copying them, memorizing their requests for different types of affection, and adjusting to their comments about my facial expressions and body language.

“You’ve done a lot of work,” my doctor said, gently. “Most people don’t have to do that much work.”

I’m finding a new community

Now that I’ve accepted my diagnosis and spent a year learning the way these diagnoses play out for people like me, I’ve found new neurodivergent colleagues and friends. The medication helps me focus in a softer way and reduces my anxiety. With the help of my community, I’m discovering ways to teach myself to listen and focus better. While I’ve stopped buzzing around and completing too many projects, I now make better decisions about my time management and find more joy in what I do take on.

While the challenges with my son were difficult for him and our family, I’m grateful for the journey we endured. We’re learning to navigate our own ways of thinking, support the parts of our brains that make our lives more challenging, and to see our strengths too.