Northwestern’s hazing history: Cases over 150 years show how hard it can be for colleges, institutions to extinguish these rituals

Angie Leventis Lourgos | The New York Times (TNS)

Accusations of hazing on Northwestern University’s football team shook the school this summer, and the fallout continues as former athletes from a variety of sports come forward with new allegations of abusive behavior, bullying, and a toxic culture.

Nonetheless, hazing has been a problem at the prestigious university for well over a century, from cases involving athletic teams and Greek life to class warfare between sophomores and incoming freshmen.

A high-profile case nearly a century ago had particularly tragic consequences when an 18-year-old student went missing after participating in an annual freshman-sophomore hazing event, a case that remains unsolved to this day.

According to the claims of some former athletes in lawsuits filed against the university this summer, the allegations this summer demonstrate the trauma and emotional damage that hazing can inflict.

“No teammate I knew liked hazing,” a former football player told the Chicago Tribune in July. “Regardless of our roles at the time, we were all victims.” But the culture was so strong that we felt we had no choice but to conform in order to survive, be respected, and gain trust.”

The history of hazing at Northwestern shows how difficult it can be to eradicate this type of behavior, a struggle that many colleges and other institutions across the country have long faced.

Following each hazing incident at Northwestern, authorities typically pledged to put an end to these types of initiation rites, sometimes disciplining or threatening action against the perpetrators. Nonetheless, the cycle appears to continue, with new allegations emerging on campus years or decades later.

“Hazing is a human problem that exists across cultures, group types, campuses, and time,” said Gentry McCreary, CEO of Dyad Strategies and a hazing researcher at colleges and universities. “Northwestern would not be alone in attempting to address the issue and failing, because hazing is a more deeply ingrained cultural issue than people are willing to admit.” … It’s a much more complicated problem than most people realize.”

Here are a few notable stories about hazing at Northwestern over the last 150 years:

Guilty as a freshman

According to the Chicago Tribune, a masked band of “bulldozers” forcibly entered two Northwestern students’ apartments one night in December 1876 in two “aggravated cases of hazing.”

“The poor unfortunates were subjected to mock trials, found guilty of the heinous crime of being freshmen, and condemned to nakedness and bed,” according to the article. “And the sentence was literally carried out, the victims being stripped of all their clothing and tenderly put to bed upon the slats, (and) the mattresses, tables, desks, chairs, and other fixtures of their room being piled above them.”

These “facts were promptly reported to the faculty,” who began looking for the perpetrators, “who will doubtless be severely dealt with if a case can be made against any of them,” according to the story.

‘Cane rush’ admonished

In May 1894, Northwestern’s president chastised students for a recent “cane rush,” a hazing event in which members of one class attempted to steal from members of another class — often violently — the ornamental walking canes that were traditionally carried.

While no one was punished, the president says new students will be “required to pledge themselves to refrain from all manner of hazing” in the future.

The annual freshman-sophomore brawl

A Northwestern freshman went missing in September 1921 after an annual hazing event known as the “freshman-sophomore fight,” which often involved students kidnapping members of the opposing class and “ducking” them into Lake Michigan.

According to the Tribune, Leighton Mount, 18, was last seen at the hazing event and never returned home.

On campus, there were many theories about Mount’s death. Some thought he committed suicide because his girlfriend didn’t reciprocate his feelings. His mother was concerned because he was alive but had amnesia. The university president dismissed the whole thing, claiming at one point that Mount wasn’t even a student because he temporarily missed a tuition payment, which Mount’s mother vehemently denied. Others suspected Mount had been kidnapped and was still being held captive.

During the hazing, another student, Arthur Persinger, was discovered tied up and hanging upside down in the lake, “with waves breaking over him,” according to the Tribune.

Persinger told authorities that he was kidnapped from his fraternity house by four men who tied him to a tombstone in a cemetery and left him there for hours after he was rescued. Persinger claimed that his kidnappers later returned to bind and gag him, dump him in a canoe, and paddle him out into the lake, where his body was reattached to the pier and hung upside down in the water.

A Tribune article described the annual freshman-sophomore brawl that year:

“The night’s climax came around midnight when nearly 1,000 freshmen and sophomores met in a pitched battle at Fountain square,” according to the article. “Many windows and heads were shattered, clothing was ripped to shreds, and yelping students in cars charged into the melee, flinging decaying vegetables.”

In a stunning discovery, police uncovered Mount’s remains in May 1923 after a 12-year-old boy discovered a human bone in an old breakwater. The bone turned out to be a piece of Mount’s skeleton, which was discovered near where Persinger was tied to the pier and rescued.

Mount’s mother informed authorities that a silver belt buckle with the initials L.M. The teeth found at the scene belonged to her son, and a dentist later confirmed that they were Mount’s remains. According to a physician, the bones were treated with acid in order to conceal the victim’s identity.

“The boy was murdered,” said the Evanston police chief at the time, according to the Los Angeles Times. “He didn’t crawl in there expecting to die. The men who murdered him shoved his body inside and hid it. If I have to question the entire student body, I will find the murderer.”

According to the Tribune, hazing was declared illegal at Northwestern a few days later by the police chief. The state’s attorney questioned the president’s son and nephew about Mount’s disappearance; both denied knowing anything about Mount’s disappearance, but the son also refuses to divulge “matters which he considered fraternity secrets” to prosecutors, according to the Tribune.

The circumstances surrounding Mount’s death remain unknown, and no one has ever been convicted in the case.

However, at the start of the first school year after Mount’s bones were discovered, the Tribune reported peace between freshmen and sophomores in September 1923. According to the article, Northwestern officials warned that “any disturbance or indication of a fight between the sophomores and freshmen will result in the men involved being immediately dismissed from the university.”

“This calm contrasted with the battling that had previously inaugurated the college year, before the tragedy of Leighton Mount cast a shadow of death over Northwestern’s annual sophomore-freshman fight,” the Tribune reported. “There was no posting of ‘proclamations’ to new students this year, no frantic skirmishing in Evanston’s streets.”

A ‘pileup’ injury with no university repercussions

In March 1937, a freshman was injured at a Northwestern fraternity during a “hell week stunt,” referring to the practice of subjecting fraternity pledges to a week of hazing prior to initiation.

According to the Tribune, the accident occurred “as a result of a pileup of 17 students during the fraternity’s ‘hell week’ festivities.” Despite the fact that the 20-year-old was hospitalized “in a serious condition, with his neck muscles and ligaments strained” and the injury had been reported to police, “when questioned later, the fraternity members refused to discuss the accident,” according to the article.

According to a university official, Northwestern will not take any action because “the boy seems to be improving,” and his condition initially appeared worse because “he was tired and worn out from loss of sleep during the ‘hell week’ activities.”

Deserted in Lake County

The Northwestern chapter of Sigma Chi fraternity was placed on probation for the remainder of the school year in February 1951 after two pledges were left in Lake County without money or identification as part of a hazing ritual; the chapter was barred from social activities and intramural athletics, according to the Tribune.

“We have campaigned against hazing in our university for years, and each fraternity president has been instructed regarding the written rules,” the university dean of students said at the time.

‘Hell Week’ is renamed ‘Help Week.’

To put a positive spin on fraternity recruitment, Phi Kappa Sigma members at Northwestern University replaced “hell week” in January 1952 with a service project for initiates called “help week.”

According to a Tribune report, seventeen freshmen spent a week volunteering at a local nonprofit before being initiated into the fraternity. The president of the fraternity and the member in charge of initiation “reported that the pledges preferred these assignments to hazing, which would have been their lot under the old system,” according to the Tribune.

A Supreme Court justice has called for the abolition of hazing.

According to the Tribune, at the annual Big Ten university sorority and fraternity conference held at Northwestern in April 1964, Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark, who was also a national officer of a fraternity, told students that hazing should be prohibited.

“Changing times call for changing treatment,” he said during a lecture to students from various universities, including Northwestern.

Breaking windows and throwing eggs

Following hazing violations during initiation week in March 1967, the university’s Interfraternity Council initiatory board fines five Northwestern fraternities and reprimands another. According to a Tribune report, the highest fine was $300 for “window breaking and egg throwing.”

The beluga whale and the flask

The largest fraternity at Northwestern, Kappa Sigma, was placed on probation after a pledge was hospitalized after an alcohol incident during a scavenger hunt event called a “pledge dad hunt” in 2002. As a result of the investigation, the university’s Interfraternity Council established a hazing hotline and pledge educator courses, according to The Daily Northwestern.

“We are in a precarious situation,” said the president of the university’s Interfraternity Council, according to the student newspaper. “On the one hand, you have a possible hazing violation, but as an institution of higher learning, we should feel obligated to help Kappa Sigma learn and grow from the incident.”

However, Kappa Sigma was suspended by the university and had its charter revoked by the fraternity’s national organization in 2003 after allegations of vandalism, alcohol use, safety issues, and reckless behavior — as well as animal endangerment — during a spring formal held at the Shedd Aquarium, which violated the terms of the probation agreement.

According to fraternity members, the animal endangerment charge “stemmed from a fraternity member dropping a closed flask in the beluga whale tank.” The whale then returned the flask to its trainer, who returned it to the fraternity member, according to The Daily Northwestern.

According to the Tribune, the flask contained Southern Comfort whiskey.

According to the New York Times, the fraternity created special shirts that read, “Kappa Sigma — a Whale of a Good Time.”

Online photos of women’s soccer players show hazing

According to the Tribune, Northwestern suspended its women’s soccer team in May 2006 pending an investigation after photos surfaced online depicting alleged Northwestern soccer players wearing only T-shirts and underwear, some blindfolded and others with their hands tied. According to a Tribune report, words and pictures were scrawled on some of the women’s bodies and clothing, and it appeared that some were drinking alcohol.

As a result of the fallout, the university revealed another recent case of hazing on the men’s swimming team, as well as a hazing incident involving the university’s mascot.

According to a university news release, hazing on the swimming team included underage drinking, having new members swim in Lake Michigan when the beach was closed, and “additional inappropriate behavior” that violated the school’s anti-hazing program. The swimming team’s training trip to Hawaii was canceled, and the team was placed on disciplinary probation; members were required to participate in a team community service project and attend anti-hazing education sessions.

Another hazing incident occurred when “students staged a fake abduction of new students who were candidates to play the role of the mascot,” according to a news release.

“When the University discovers allegations of hazing or other violations of student conduct regulations, it will respond quickly and take the appropriate actions,” according to the news release.

‘In praise of hazing’

Following the publication of the women’s soccer photos online, a Northwestern sociology professor wrote an opinion piece for the Chicago Tribune in June 2006 titled “Kids gone wild? In support of hazing,” though he admitted that “initiations can go too far at times.”

“Hazing is good for America,” the professor wrote in an opinion piece. “Those of us who have gone through fraternity (and some sorority) initiations, which were once a cherished part of campus life, know that they foster a sense of shared honor and pride.” However, in today’s no-risk, litigious, surveillance society, such rituals have been reduced. Whereas we used to accept the rough-and-tumble of youth culture, everything is now scrutinized through the thorny eyes of lawyers.”

Hazing scandal in football

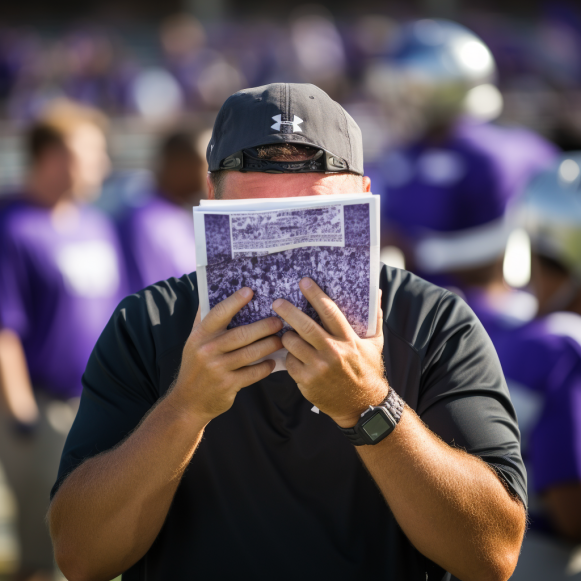

On July 10, Northwestern President Michael Schill fired head football coach Pat Fitzgerald for “failure to know and prevent significant hazing in the football program.”

The shocking leadership change occurred just a few days after Fitzgerald was suspended for two weeks without pay following an independent investigation into hazing allegations, the results of which were not made public.

“The hazing included forced participation, nudity, and sexualized acts of a degrading nature, all of which were clearly in violation of Northwestern policies and values,” Schill said in a statement.

The university fired its head baseball coach a few days after Fitzgerald was fired, citing bullying and abusive behavior.

Several former Northwestern athletes from various sports have filed roughly a dozen lawsuits against the school in the aftermath of the hazing scandal. A former volleyball player has accused the volleyball team of long-standing hazing, harassment, bullying, and retaliation. Several former Northwestern football players described racial discrimination as well as rampant sexualized hazing.

On Monday, three former baseball staff members sued Northwestern, claiming the university failed to protect them and student athletes from a “abusive, toxic, and dangerous environment.”

“This lawsuit is without merit, and the university intends to contest it vigorously,” Northwestern said in a statement.