Recession signs are flashing in 44 states as tariff risks and DOGE cuts threaten growth

Unemployment has jumped significantly in 44 states, Rosenberg Research said.

Critical minerals experts have been watching President Donald Trump’s minerals deal with Ukraine unfold with more than a little puzzlement.

On Monday, Trump said a revenue-sharing agreement on Ukrainian critical minerals would be signed soon. Rare earth elements have been a key focus of the proposed deal, with Trump repeatedly referencing them.

Yet “I cannot find credible evidence of rare earth deposits in Ukraine. At all,” Laura Lewis, a professor in chemical, mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern University’s College of Engineering, told B-17.

Erik Jonsson, a senior geologist at the Geological Survey of Sweden, said that “Ukraine has a solid mining industry, but it’s not based on rare earths.”

Seeking $500 billion

Initially cast as a stepping stone toward Russia-Ukraine peace talks, the status of the proposed deal has been in limbo for some time.

At the end of February, a tense Oval Office meeting between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy looked like it might blow up the deal.

But days later, Zelenskyy said he was ready to sign it, and Trump, speaking to reporters on March 3, said it’s “a great deal for us” offering “the finest rare earths.”

A tense exchange between Trump and Zelenskyy in February seemed to put the deal on ice.

The proposed deal made public in late February agreed on the joint exploitation of government-owned Ukrainian “natural resource assets.” It’s unclear what the US would provide other than vague security assurances.

Trump has framed the deal’s potential profits as a means of recouping the cost of military aid to Ukraine.

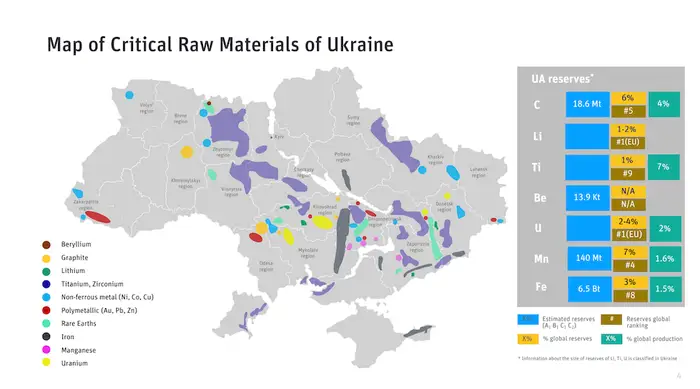

The deal covered a sprawling amount of materials including critical mineral deposits and fossil fuels. Some of these, like titanium and graphite, are already being successfully mined as major industries in Ukraine.

But it’s rare earth elements that generated real excitement in the White House.

These are a subset of critical minerals — materials in high demand in industries like military and consumer tech that governments consider essential to national security.

Trump has attached particularly large figures to the value of Ukrainian rare earth elements, telling Fox News last month that he wants “like $500 billion worth of rare earth” from the partnership.

“It could be a trillion dollar deal, it could be whatever, but it’s rare earths and other things,” he said a few weeks later.

The problem is that the public evidence base for a significant presence of readily exploitable rare earths in Ukraine is remarkably thin.

Experts ask for the data

“I was surprised when I first saw” the emphasis on rare earth elements, Lewis told B-17.

She’s not alone. Specialist outlets such as the International Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute have also been highly skeptical.

Jonsson told B-17 he was especially surprised by the kind of figures being discussed around Ukraine’s rare earth elements, and its mineral resources in general.

Ukraine’s publicly available mapping of critical metals and minerals appears to be based on Soviet-era surveys, and Jonsson and Lewis say these fall far short of what an investor would need to move ahead confidently.

A 938-hectare deposit in Novopoltavske, in Zaporizhzhia, said to have rare earth elements, for example, was last properly examined in 1991, according to the State Geologic and Subsoil Survey of Ukraine.

A map of “Critical Raw Materials of Ukraine,” including rare earths, published by the Ukrainian Geological Survey as part of a brochure of investment opportunities.

While the Ukrainian Geological Survey has published a brochure of investment opportunities around sites like this, the data in these documents simply aren’t enough to make a real judgment, Jonsson said.

“The main point is we don’t know what kind of investigations there have been,” he added. To be able to say what’s there, Jonsson said he’d need a far more detailed report outlining “every drill hole.”

This doesn’t mean Ukraine doesn’t have any usable rare earth elements.

“They probably have it,” he said, but in publicly available reports, some are only mentioned alongside other elements as a “sort of second or third commodity,” he said.

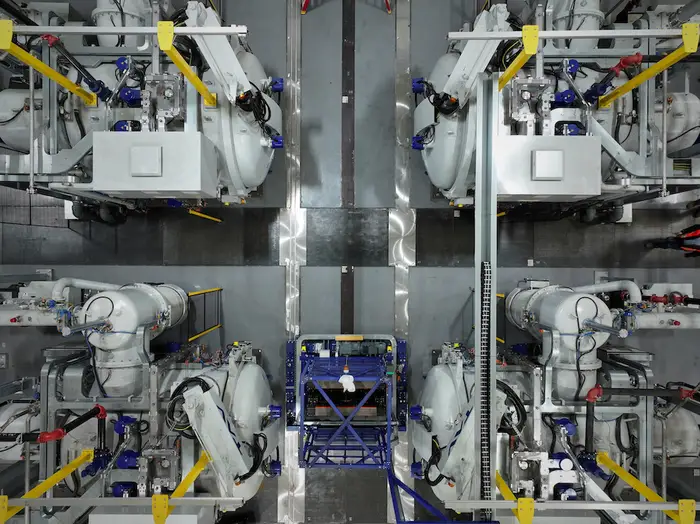

Specialized furnaces process rare earth elements for the production of magnets.

A tough, long-term prospect

Rare earth elements don’t just sit there waiting to be hacked out of the ground — some occur as oxides, which involve intensive chemical processes and, increasingly, emerging technology to extract and process.

“Just because you have something in the ground does not mean that you’re going to be able to get a metal form of it that will go into technology,” Lewis said.

It would probably take “multiple billions” of dollars and around 15 years to get production really under way, she said.

Ukrainian authorities didn’t respond to requests for comment.

There’s also a war on

Some analysts have previously told B-17 they are concerned about the US’ supply of rare earths, citing a lack of transparency around the size of national stockpiles.

The US State Department didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Trying to get access to natural resources into the process of making a peace deal is a “novel arrangement,” Rebecca Seidl-Inglesby, the lead expert in critical minerals and metals at Baker-Botts law firm, told B-17.

“With this amount of uncertainty, I cannot think of another example even comparable to this,” she said.

But investors want certainty over things like land rights and the quality of infrastructure — which have huge question marks in war-torn, partially-occupied Ukraine, she said.

A train passing damaged railway lines 10 km from the frontline in November 2024, in Pokrovsk, Ukraine.

In fact, several of the prospective rare earth sites highlighted by the Ukrainian Geological Survey are under Russian occupation.

(One aspect of the deal that appeals to some Ukrainian commentators is that it gives the US a stronger stake in the country’s long-term security.)

“I think the private sector will certainly be interested in continuing to watch this, but it would be difficult, especially given how capital-intensive these projects are,” Seidl-Inglesby said.

There’s another source of long-term uncertainty that could also be offputting to investors, said Gavin Harper, a research fellow in critical materials at the UK’s University of Birmingham.

The Budapest Memorandum — signed in 1994 by Ukraine, the US, the UK, and Russia after Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal — ruled out “economic coercion” or any attempt to “secure advantages of any kind” as part of security assurances given in the interests of Ukraine’s sovereignty.

Harper said Trump’s attempt to leverage Ukraine’s vulnerability for economic gain in the middle of a war “contravenes both the spirit and the letter” of the agreement.

Speaking to CNN last month, Ben Wallace, the UK’s former defense minister, blasted the mineral deal, describing it as “extortion” against Ukraine.

Russia has, of course, ignored the Budapest Memorandum many times in attacking Ukraine. But for US investors, reliability in the eyes of international law is a “foundational thing,” Harper said.

For Lewis, out of all the possible critical minerals in Ukraine that the US could potentially invest in, “rare earths are not it.”